A new 3D printing technique can produce multimaterial 3D-printed models more rapidly and with a higher resolution than traditional techniques by converting MRI and CT scans into a series of black and white pixels, according to a study published online May 29 in 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing.

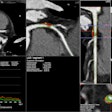

Most medical images that are compatible with 3D printing have a high resolution and provide so much detail that areas of interest need to be identified and separated from surrounding tissue through manual segmentation or automated thresholding. However, these processes are time-consuming and limited by the presence of image artifacts that tend to either overexaggerate or wash out key features -- often resulting in imprecise 3D-printed models.

To circumvent these complications, researchers from Harvard University and various academic institutions and medical centers in the U.S. and Germany developed a new method for making 3D-printed models. The technique hinges on converting MRI and CT scans into a digital file format, known as a dithered bitmap, that consists entirely of black and white pixels. Instead of using several shades of gray to distinguish structures the way typical medical images do, bitmaps use varying sizes of black pixels to convey shading.

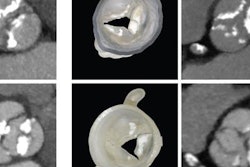

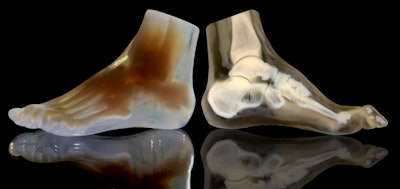

3D-printed foot (left) and corresponding cross section (right) reveal the internal structure of the foot bones and surrounding soft tissue. Image courtesy of Steven Keating, PhD, from Harvard University and Ahmed Hosny, PhD, from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

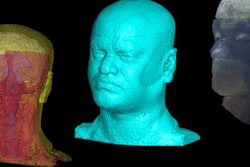

3D-printed foot (left) and corresponding cross section (right) reveal the internal structure of the foot bones and surrounding soft tissue. Image courtesy of Steven Keating, PhD, from Harvard University and Ahmed Hosny, PhD, from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.By simplifying the numerous shades of gray into black and white pixels using an automated algorithm, the group was able to bypass image segmentation and directly create 3D prints of complex anatomical models that preserved subtle variations evident in the original MRI and CT scans, including those of the brain of co-first author Steven Keating, PhD. On average, the researchers were able to process the images before printing them with a multimaterial 3D printer (Connex500, Stratasys) in several minutes.

"Our approach not only allows for high levels of detail to be preserved and printed into medical models, but it also saves a tremendous amount of time and money," senior author Dr. James Weaver, PhD, said in a article by the Wyss Institute at Harvard University. "Manually segmenting a CT scan of a healthy human foot, with all its internal bone structure, bone marrow, tendons, muscles, soft tissue, and skin, for example, can take more than 30 hours, even by a trained professional -- we were able to do it in less than an hour."

The researchers hope that the technique's enhanced physical visualization can open the door for 3D printing applications in new areas of medical research.

"I imagine that sometime within the next five years, the day could come when any patient that goes into a doctor's office for a routine or nonroutine CT or MRI scan will be able to get a 3D-printed model of their patient-specific data within a few days," Weaver said.