Advances in virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) have prompted new developments in cardiovascular imaging that may improve clinician training as well as patient care and outcomes, according to a review article in the June issue of JACC: Basic to Translational Science.

Dr. Jennifer Silva from Washington University School of Medicine.

Dr. Jennifer Silva from Washington University School of Medicine.

"For years, virtual reality technology promised the ability for physicians to move beyond 2D screens in order to understand organ anatomy noninvasively ... [but] bulky equipment and low-quality virtual images hindered these developments," Silva said in a statement released by the American College of Cardiology (ACC). "Recent hardware and software developments [to VR technology] -- such as head-mounted displays and advances in display systems -- have enabled new classes of 3D platforms that are transforming clinical cardiology."

Virtual reality continuum

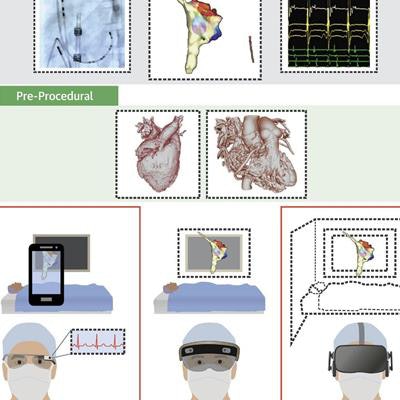

Recent developments in advanced visualization technologies have considerably expanded the world of "extended reality," which Silva and colleagues defined as a spectrum bookended by VR on one end and AR on the other. This continuum includes four major types of visualization experiences that have demonstrated potential applicability in healthcare (JACC: Basic to Transl Sci, June 2018, Vol. 3:3, pp. 420-430):

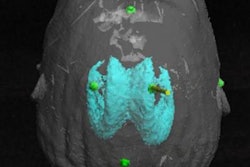

- Virtual reality: VR requires complete visual and auditory immersion into a synthetic environment in which users can experience altered versions of reality. Clinicians have used VR to enhance the diagnosis of brain aneurysms and to simulate liver surgery, for example.

- Merged reality: Similar to VR, merged reality involves full immersion but with a focus on displaying a real-life environment, which is ideal for transporting users to a specific setting such as a hospital room.

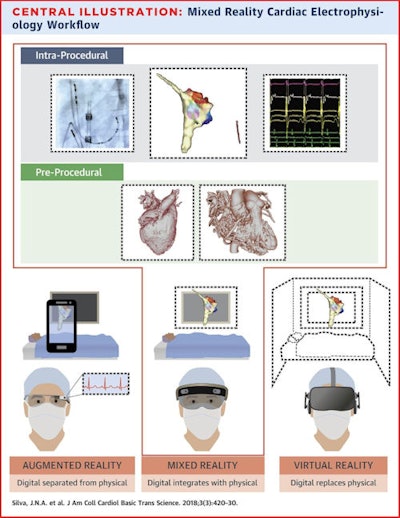

- Mixed reality: This technology projects virtual objects onto a semitransparent display that allows users to see and interact with both the virtual objects and their actual surroundings. Mixed reality is a variation of AR that has risen in popularity to facilitate presurgical planning and guide complex procedures.

- Augmented reality: AR also allows users to see a virtual image within their native environment, but it offers limited interaction with the virtual image. In the medical setting, clinicians can use AR to refer to relevant information along with their physical surroundings, such as projecting CT or MRI scans directly on the patient's body.

"These technologies are still constrained due to cost, size, weight, and power to achieve the highest visual quality, mobility, processing speed, and interactivity," Silva said. "Every design decision to mitigate these challenges affects applicability for use in each procedural environment."

Yet early research has shown that the improved visualization of these technologies may help clinicians as they interpret images and perform procedures -- transforming clinical practice, she said. Ultimately, these improvements have the potential to lower the cost of treatment and improve outcomes for patients.

Mixed reality allows for the integration of VR with existing displays within the cardiac catheterization suite, including fluoroscopy (top left), electroanatomic mapping systems (top center), and electrocardiograms (top right), as well as CT and MRI 3D models (middle row). Image courtesy of the ACC.

Mixed reality allows for the integration of VR with existing displays within the cardiac catheterization suite, including fluoroscopy (top left), electroanatomic mapping systems (top center), and electrocardiograms (top right), as well as CT and MRI 3D models (middle row). Image courtesy of the ACC.Cardiac applications

There are numerous examples of this early research in cardiovascular imaging and care, with most of the applications falling within the following categories:

- Education: VR has provided a new outlook for cardiac anatomy and pathology that has improved depth of understanding not only for medical students and residents but also for patients, the authors noted. The Stanford Virtual Heart Project -- geared toward patient and student education at Stanford Medicine -- is a growing VR library that includes roughly two dozen congenital cardiac lesions.

- Preprocedural planning: By wearing a VR headset, clinicians can review on-screen images such as CT angiography scans while simulating challenging procedures. Studies such as the one conducted by Chan et al have shown that presurgical planning with VR can reduce image interpretation times and maintain accuracy compared with a traditional display.

- Intraprocedural visualization: AR technology empowers clinicians to visualize and manipulate patient-specific 3D heart models using gesture, gaze, and voice control during operations, the authors wrote. With shared functionality, AR can display a single holographic model of the heart for multiple users in the same room.

For example, Bruckheimer and colleagues from Schneider Children's Medical Center demonstrated the viability of using AR holograms based on 3D rotational angiography and 3D transesophageal echocardiography scans to facilitate real-time cardiac catheterization. - Rehabilitation: Multiple studies have shown that neurorehabilitation combining VR and other brain imaging technologies has helped poststroke patients retrain their brains to improve upper limb mobility.

As extended reality technology continues to evolve, so, too, will the visualization of the heart, according to the authors. This improved visualization will allow clinicians to learn more quickly, interpret images more accurately, and accomplish interventions in less time.