HONOLULU - What are the predominant applications of 3D printing in healthcare, and what lies ahead for the technology? Radiologists from the U.S., Canada, and South Korea envisioned a bright future for medical 3D printing in a Sunday featured course at the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS) 2019 meeting.

Many current medical applications for 3D printing already exist, all of which can be organized into four overarching categories:

- Personalizing patient care

- Teaching and training

- Bioprinting (e.g., tissue and organ fabrication)

- Pharmaceutical research

Among these, the individualization of medical care may have the most meaningful effect in the near term and seems to be most relevant for radiologists, Dr. Jane Matsumoto of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, told course attendees.

"It really all comes down to care, and it's not just care -- it's individualized medicine," she said. "3D printing is the ultimate individualized medicine. You take what's unique to a patient, and because you can use 3D printing you help take care of them in a way that you wouldn't be able to otherwise."

Personalized patient care

At Vanderbilt University's 2018 Tikkun Olam Makers (TOM) makeathon, participants were asked to present a simple, mostly homemade solution to a real medical scenario. The challenge? Figure out a way to enable a 5-year-old boy with dysmorphic hands to write.

Dr. Sumit Pruthi and colleagues from Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt eagerly accepted the charge. They purchased Play-Doh from a local convenience store and used it to make a mold of the boy's hand. Then they digitized the clay mold using a high-resolution optical scanner and turned it into a cast. By wearing the cast, the boy was finally able to hold on to a pen and write without additional assistance.

"This is an example of using a technology that is not only cutting edge on its own terms but can be very simple to use and really transformative for someone's life," Pruthi, chief of pediatric neuroradiology at the hospital, said during his talk.

Following this spirit of innovation, researchers at Vanderbilt have been using 3D printing to solve a variety of medical problems by personalizing patient care. In the context of neuroradiology, Pruthi classified the ongoing work into several distinct components:

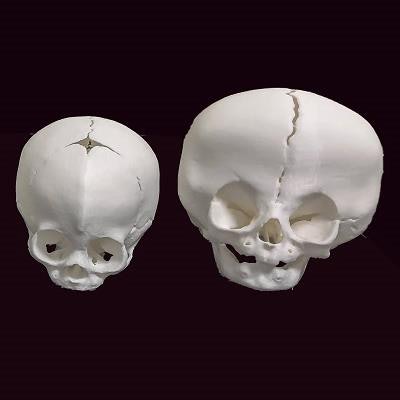

Improving patient understanding: When it comes to neurosurgical procedures, particularly craniosynostosis, patients typically have a lot of questions -- about the surgery, why the incision has to be so long, and why they have to undergo surgery at all, Pruthi noted.

"Having a 3D model of the bone, which they can hold in their hand, can help them understand what the surgeon is trying to achieve," he said. "The whole idea here is to [encourage] informed decision-making, which then sets expectations appropriately."

- Improving patient comfort: Neuroradiologists have relied on 3D printing to construct face-immobilization masks, among other objects, that are individually tailored to patients based on their MRI scans. These objects must also conform to specific requirements that allow for use inside an MRI system.

Enhancing diagnostic quality: The production of patient-specific 3D-printed models demands high-resolution imaging data, with negligible discrepancy between the model and diagnostic images. As a result, the 3D-printed models offer highly accurate visualization of, and tangible interaction with, patient anatomy.

For intricate cases such as craniofacial trauma, holding a 3D-printed model in one's hand is worth more than a thousand words or, in this case, images, Pruthi said.

- Presurgical planning and navigation: Possibly the most widely employed application of medical 3D printing is helping surgical teams plan and simulate procedures before they set foot in the operating room. Numerous case studies have confirmed that supplementing presurgical planning with 3D-printed models can reduce operating times, boost surgical accuracy, and improve functional outcomes.

- Creating customized parts, prostheses, and implants: Neuroradiologists at Vanderbilt, for example, have used medical images of the faces of children with a craniofacial deformity to create customized 3D-printed masks for them.

3D-printed skulls based on CT scans. Image courtesy of Dr. Sumit Pruthi.

3D-printed skulls based on CT scans. Image courtesy of Dr. Sumit Pruthi.Recent advances

Despite these potential benefits, the everyday clinical application of 3D printing has been restricted by a number of barriers. For radiologists, one of the primary deterrents is the time-consuming labor required for image segmentation. Manually segmenting a set of data from a single patient can take roughly eight hours, time that most clinicians do not have the luxury of offering, unless they are willing to put in additional work during off-hours.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) may be the key to overcoming this particular barrier. To prove the case, Namkug Kim, PhD, and colleagues from Asan Medical Center in South Korea have developed a deep-learning algorithm capable of automatically segmenting CT scans -- shaving the lengthy process down to a matter of seconds. As it is an AI-augmented (not AI-commandeered) workflow, a radiographer or radiologist would still need to review the images for accuracy.

Perhaps more promising still, the American Medical Association has already approved four new category III current procedural terminology (CPT) codes for individually prepared 3D-printed anatomic models, which will take effect on July 1.

The national healthcare system in South Korea has already begun offering insurance coverage for 3D-printed cardiac models that have been deemed cost-effective; reimbursement varies by hospital. With coverage an impending possibility in the U.S., the clinical application of 3D printing may really begin to ramp up in the coming years, Nicole Wake, PhD, from Montefiore Medical Center noted in her talk.

"Clinicians, including radiologists, need to take advantage of the CPT codes or they will lose them," added Dr. Adnan Sheikh, medical director of 3D printing at the Ottawa Hospital. "It's an investment and requires collaboration with engineers, but if you don't start making use of it now, you're going to miss out on the opportunity."

Better radiologists

3D printing will be a part of medicine going forward, and now is an opportune time to get involved, Matsumoto said at the close of the 3D printing seminar. To help promote this goal, radiologists should remain open to working with other clinicians, and, together, maintain dialogue with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on regulatory and compliance issues.

Indeed, it was the joint meeting between the FDA and the RSNA 3D printing special interest group in August 2017 that spearheaded the formation of the upcoming CPT codes.

This kind of interspecialty cooperation has been the modus operandi of medical 3D printing for years, and the future of 3D printing will rely on this continued push for collaboration, Matsumoto noted.

"Ultimately, you build closer working relationships with your colleagues. It's a new, really positive interaction, and you learn a lot as a radiologist," she said. "I feel like I'm a better radiologist for doing 3D printing."