A new technique based on photoacoustic imaging could help surgeons determine whether they've removed all cancerous tissue during breast surgery, according to a study published online May 17 in Science Advances.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the California Institute of Technology have developed the technology to scan a tumor sample and produce images accurate enough to determine whether a tumor has been completely removed. They are working to make the technique fast enough to be used during surgery.

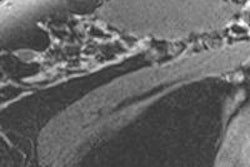

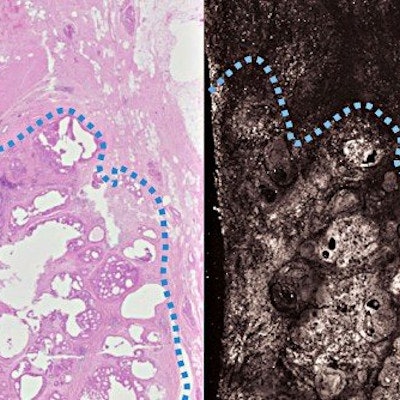

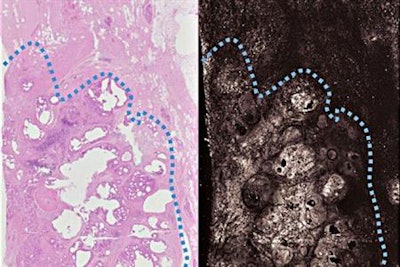

The new technique (right) produces images as detailed and accurate as the frozen section method (left), but in far less time. Cancerous breast tissue is below the dotted blue line. Credit: Terence T. W. Wong.

The new technique (right) produces images as detailed and accurate as the frozen section method (left), but in far less time. Cancerous breast tissue is below the dotted blue line. Credit: Terence T. W. Wong.The technology could be a boon to women undergoing lumpectomy, since about a quarter of them have to undergo a second surgery because part of the tumor remains.

Currently, there is no accurate method to determine whether all cancerous tissue has been removed during surgery, according to the team led by Dr. Deborah Novack, PhD. For solid tumors in most parts of the body, doctors use what's called a frozen section to check the excised lump's margins. But this doesn't work well on breast specimens, which are therefore sent to a pathologist; surgeons receive the results after a few days.

The new technique is based on the photoacoustic effect: When a beam of light of the correct wavelength hits a molecule, some of the energy is absorbed and then released as sound in the ultrasound range, Novack and colleagues wrote. These sound waves can be used to create an image.

"[Our study] is a proof of concept that we can use photoacoustic imaging on breast tissue and get images that look similar to traditional staining methods without any sort of tissue processing," Novack said in a statement released by Washington University School of Medicine.

The researchers are applying for a grant to build a photoacoustic imaging machine with multiple channels and fast lasers. Their ultimate goal is to have a machine that could be located in the operating room; specimens could be run through the machine during surgery to ensure that the entire tumor has been excised.