An artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm initially cleared for analyzing chest x-rays of adult patients may also be effective for use with children, according to a study published June 17 in Scientific Reports.

South Korean researchers investigated the potential of a commercially available algorithm (Insight CXR, v. 3, Lunit) for spotting abnormalities in specific pediatric age groups. They found that it achieved nearly 97% accuracy when cardiomegaly and children 2 years old and younger were excluded. These results could help kick-start clinical development of AI software in this population, according to the authors led by corresponding author Dr. Eun-Kyung Kim, a radiologist at Yonsei University College of Medicine in Seoul.

Lunit's Insight CXR received Europe's CE mark in 2019, and it is designed to help analyze chest x-rays to detect 10 major abnormalities, such as nodules, calcification, pneumothorax, consolidations, and fibrosis, that could be signs of lung disease. It also supports screening for tuberculosis.

Validating algorithms already approved for adults could be a new approach for developing the technology for use in children, given a scarcity of AI software available for pediatric patients, the authors wrote.

To that end, the group culled 2,273 images of patients under 18 years old (mean age 7.0 ± 5.8 years old) who underwent chest x-rays at their hospital in Seoul from March to May 2021. A pediatric radiologist with 11 years of experience studied each image for positive and negative results, which served as standard reference for assessing the software's performance.

The algorithm was tested first for identifying eight detectable lesions: nodules, consolidation, fibrosis, atelectasis, cardiomegaly, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, and pneumoperitoneum. In these cases, the software achieved an accuracy of 87.5%.

Next, the researchers excluded cardiomegaly (enlarged heart), given that different criteria are used to diagnose the condition in adults and young children, whereby the software achieved an accuracy of 89.5%.

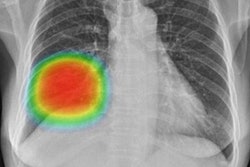

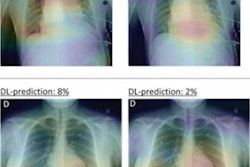

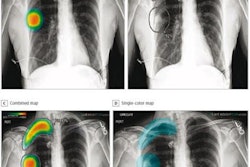

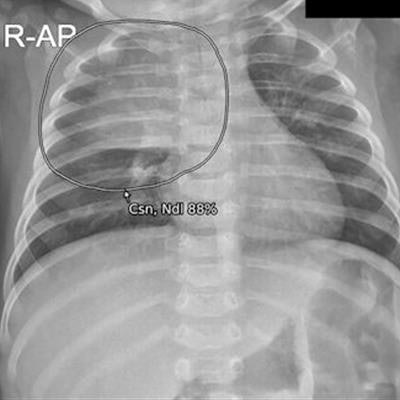

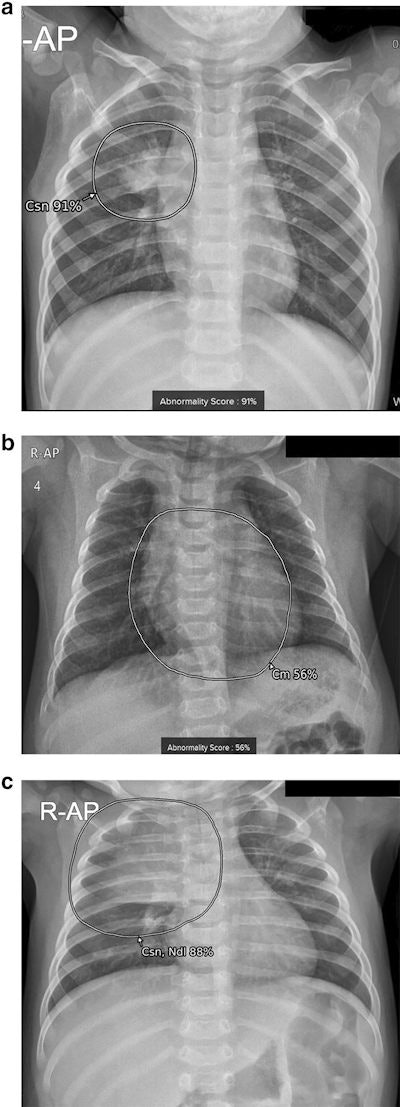

Examples of results analyzed by the AI-based lesion detection software. (A) A 17-month-old boy with pneumonia in the right upper lobe. The software detected consolidation with an abnormality score of 91% in the right upper lobe, as marked in the grayscale map. (B) A 3-month-old boy with a cardiothoracic ratio of 50%, within normal range. The software detected cardiomegaly with an abnormality score of 56% on the anteroposterior chest radiograph. (C) A 4-month-old girl without remarkable findings on the chest radiograph. The software detected normal thymus as consolidation and nodule with an abnormality score of 88%. Image courtesy of Scientific Reports.

Examples of results analyzed by the AI-based lesion detection software. (A) A 17-month-old boy with pneumonia in the right upper lobe. The software detected consolidation with an abnormality score of 91% in the right upper lobe, as marked in the grayscale map. (B) A 3-month-old boy with a cardiothoracic ratio of 50%, within normal range. The software detected cardiomegaly with an abnormality score of 56% on the anteroposterior chest radiograph. (C) A 4-month-old girl without remarkable findings on the chest radiograph. The software detected normal thymus as consolidation and nodule with an abnormality score of 88%. Image courtesy of Scientific Reports.In addition, the researchers found that images with incorrect diagnoses by the software were significantly younger than patients with correct diagnosis. When they excluded children 2 years old and younger from the analysis, the software's accuracy increased up to 96.9%, which was comparable to the diagnostic accuracy provided by the vendor for adults, the researchers wrote.

"AI-based lesion detection software can be developed and utilized for pediatric chest radiographs after further validation," the authors wrote.

The group noted that using a single commercially available algorithm could be a limitation of the study and that different software programs could have different degrees of robustness when applied to pediatric images.

Ultimately, the study is a first validation study using the approach, and future studies will focus on whether AI software approved for adult use could help clinicians either assess pediatric x-rays or find lesions that radiologists cannot detect, the authors wrote.

"AI-based lesion detection software needs to be validated in younger children with larger data to assure safe usage, and adult-oriented software can be a starting point for this," Kim and colleagues concluded.