ORLANDO, FL - The key to success for implementing clinical decision support (CDS) with computerized physician order-entry (CPOE) systems for diagnostic imaging is based on three key principles, according to a presentation at the Society for Imaging Informatics in Medicine (SIIM) annual meeting.

The following are the ingredients for success:

- Using quality evidence-based guidelines

- Implementing strong leadership

- Establishing accountability for decisions made

The costs of healthcare are steadily rising, as are the number of diagnostic imaging exams performed. Radiology as a specialty is getting a bad rap, but there is a waste of resources at every level of medicine, according to presenter Dr. Ramin Khorasani, vice chair of the department of radiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and chief of its Center for Evidence-Based Imaging.

What is particularly surprising is that in spite of the initiative to convert to electronic records and an estimated investment of $40 billion to $50 billion in health IT, the adoption of CPOE, CDS, and business intelligence analytics tools is suboptimum.

With that statement made, Khorasani asked session attendees how many had implemented CDS. One hand was raised out of 200 attendees, approximately 70% of whom worked for healthcare organizations.

Khorasani and colleagues at Brigham are pioneers, having implemented a CDS system in 1998. But, as Khorasani is quick to point out, their motivation was to improve quality in the department, not to reduce the cost of imaging for the hospital’s patients.

The radiology department had conducted analyses that showed significant variations in the ordering patterns of physicians whose patients had the same symptoms. This was compounded by concerns about overordering exams for patient follow-up.

As an example, Khorasani cited a study that showed that if a patient had undergone any type of abdominal imaging exam, 41% would undergo another study within 90 days. Only 14% of these follow-up exams had been recommended by radiologists.

When the radiology department started to investigate, it learned from expert panels that 5% to 20% of all exams performed at Brigham were inappropriate, unnecessary, or redundant. The department took action and developed a prototype CPOE system with integrated CDS.

Evidence-based guidelines

"CDS will only be accepted if based on credible, evidence-based guidelines. The strength, level, and rate of evidence has to be transparent and accessible to the decision-maker in real-time. Evidence cannot be unambiguous. It must be actionable and embedded in workflow for immediate access," Khorasani emphasized.

He said that the best local practices represent the best evidence-based guidelines, as well as those published in peer-review journals. The source of evidence must be agnostic, as good evidence may originate from many sources.

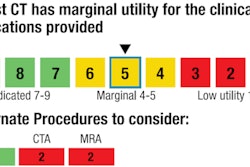

What does "appropriateness" mean? "I do not know what this means. I do not know how to differentiate a score of 6 [uncertain] from a score of 7 [acceptable]," he said. "It is important for a multidisciplinary panel to evaluate every single item of evidence relating to a diagnostic procedure."

Khorasani pointed out that while commercial CDS systems containing evidence-based guidelines have their attributes, it is essential to review every guideline and reach a consensus that this is appropriate to implement. If there is any ambiguity, or if it does not conform to local best practice, it shouldn’t be implemented.

It’s acceptable not to have a guideline for every imaging procedure. Clinicians will reject a system if there is ambiguity, or if what is recommended doesn’t make sense to them.

"Unlock only what you agree upon," he cautioned.

Evidence-based guidelines must be current, and they must be kept updated. Khorasani said that it typically takes five to 14 years after an article is published in peer-review journals for it to be adopted by some -- not all -- physicians in clinical practice.

He said that at Brigham, recommendations are vetted by a multidisciplinary panel, and if approved, they are implemented within eight to 12 weeks. An extremely high-quality article now is circulated by email, with a request to respond by email if there is disagreement.

"Always react to the advice of your colleagues. If a gastroenterologist stops you in the hall to tell you about an article that he feels would be a contribution to the CDS, act upon it. If you don’t, you’ll lose credibility," he said.

Other elements for success

Make the CDS system easy to use, with fast displays and limited mouse clicks. Brigham’s system enables physicians to create shortcut commands because 80% of all orders placed by a given physician are generally the same ones.

Screens are automatically populated with patient demographic and payor information. This enables a physician to receive a warning when an insurance company will not pay for a particular exam.

Khorasani demonstrated how a physician would receive advice about an inappropriate exam order, and how evidence is presented. Alternative exams are recommended, and analyses show that the physicians tend to follow the advice.

He also demonstrated what happens when a duplicate exam is ordered. "With this, we want to embarrass the ordering physician. We want to make sure that he or she thinks twice about what they are requesting," he said. Duplicate warning notices resulted in a 6% exam order cancelation rate.

Getting a go-ahead for some exams requires a peer-to-peer consultation before the system will let a physician proceed. Eleven radiologists carry "consultation pagers." Over time, the percentage of orders approved after consultation has steadily risen. Khorasani noted that there are always good reasons for exams and physicians are more selective in ordering exams that trigger consultations.

The system also contains a complaint and feedback request button. In 2011, it was never used once for any of the 700,000 exams ordered.

Once a physician enters an "order exam" field in the electronic medical record, that physician has entered the "Big Brother" realm of the radiology department. Every keystroke is logged. Physicians get regular reports of what they’ve done, no matter what it is. Feedback is an essential component of the Brigham CDS system.

In most cases, physicians are free to order exams, but they might be contacted in a day or so to ask why. Accountability is critical. Behavior changes when people know they are being watched or monitored. They think twice, and often by doing so make more intelligent decisions.

Implementing accountability requires a strong culture and leadership. If a radiology chairman is ambivalent about implementing a CDS system, the chances of making it work probably will be diminished, according to Khorasani. Leadership is critical because CDS represents a major change and must be supported.

That support must not be limited to the radiology department. Collaboration within the hospital is critical.

Offer a benefit to referring physicians for using the system. For Brigham, this was online scheduling when the hospital mandated that all radiology exams had to be ordered through the CPOE. The convenience of this had another benefit: Even with CDS reducing some of the exams that might have been performed, the convenience of being able to get evidence-based advice combined with online scheduling generated increased utilization. It was more convenient to schedule a CT or a MRI exam at Brigham than at some competitive Boston imaging centers. The radiology department had to purchase additional modalities to meet demand.

"It’s important to document what happens when a CDS system is implemented. It’s time to influence public policy. Changes in healthcare will happen no matter what," Khorasani said. "It’s better for the radiology profession to have a case made to utilize evidence-based guidelines for diagnostic imaging rather than go the route of preauthorization by an entity that will not be as informed as the physicians requesting exam authorization."