Some medical-legal experts claim fractures seen on x-rays in child abuse cases result from rickets and not traumatic injury, according to a U.S. group. They say this is a fringe belief and countered it recently with a study showing that radiologists can reliably differentiate between the two.

Researchers at Indiana University compared the diagnostic performance of radiologists when differentiating rickets (vitamin D deficiency) and classic metaphyseal lesions (CMLs) in sets of x-ray images. They found agreement among the radiologists was substantial to almost perfect.

"These findings counter claims that radiologists cannot reliably differentiate rickets and CML and commonly misinterpret rachitic changes as representing CML," wrote corresponding author Dr. Boaz Karmazyn, a professor of radiology and imaging sciences (American Journal of Roentgenology, July 6, 2022).

Radiologists play a crucial role in diagnosing child abuse, as fractures are the second most common finding of child abuse after bruising and other cutaneous signs. CMLs are microfractures that have been strongly associated with child abuse since they were first described in 1953.

Nonetheless, some physicians involved in medicolegal work assert that CMLs result from vitamin D deficiency and rickets and are not traumatic fractures, thus challenging the specificity of CML, according to the authors.

Moreover, these arguments provide an alternative diagnosis in cases of suspected child abuse, leading to the possibility that juries may give less consideration to radiographic findings or even that prior convictions for child abuse could be overturned, they wrote.

Thus, in this multicenter study, the researchers sought to address the issue by evaluating the diagnostic performance of radiologists in differentiating rickets and CML in children under 2 years old who underwent knee x-rays from January 2017 to December 2018. The children either had rickets (n = 70) or knee CMLs (n = 77) and a diagnosis of child abuse from a child abuse pediatrician.

Images were cropped and zoomed to present similar depictions of the knee, while eight radiologists independently interpreted the x-rays and rated their confidence levels for making diagnoses. Importantly, the radiologists were comprised of both pediatric and nonpediatric specialists with post-training experience ranging from one to 15 years.

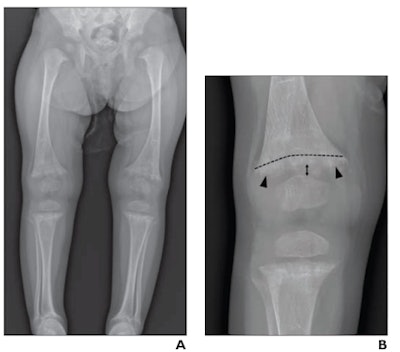

(A, B) a 21-month-old girl with rickets and vitamin D level of 5 ng/mL. (A) Long-leg bilateral lower extremity radiograph. (B) Edited radiograph of the right knee shows cupping (curved dotted line), fraying (arrowheads), and increased physeal widening (double-head arrow) in the distal femur, with similar findings in the proximal tibia and fibula (not annotated), all consistent with rickets; radiograph shows no signs of classic metaphyseal lesions. All eight radiologists correctly interpreted radiograph as showing rickets with moderate or high confidence. Images courtesy of the American Journal of Roentgenology.

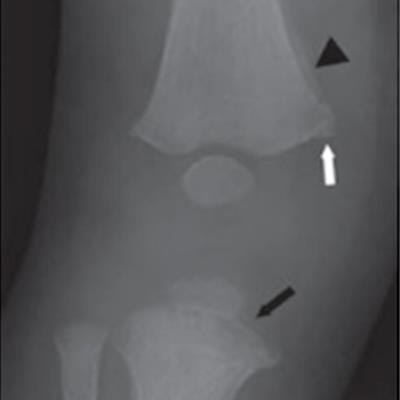

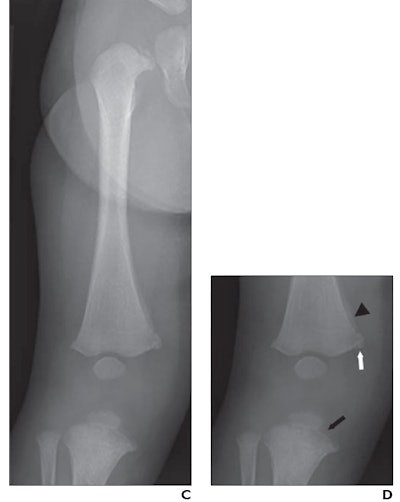

(A, B) a 21-month-old girl with rickets and vitamin D level of 5 ng/mL. (A) Long-leg bilateral lower extremity radiograph. (B) Edited radiograph of the right knee shows cupping (curved dotted line), fraying (arrowheads), and increased physeal widening (double-head arrow) in the distal femur, with similar findings in the proximal tibia and fibula (not annotated), all consistent with rickets; radiograph shows no signs of classic metaphyseal lesions. All eight radiologists correctly interpreted radiograph as showing rickets with moderate or high confidence. Images courtesy of the American Journal of Roentgenology. (C, D) a 4-month-old boy with knee classic metaphyseal lesions diagnosed with child abuse and with vitamin D deficiency (23.4 ng/mL). Child had multiple fractures other than knee CML, including multiple posterior rib fractures and fractures of the right fibula, left femur, and right first metatarsal. (C) Radiograph of proximal right lower extremity from skeletal survey. (D) Edited radiograph of the right knee shows distal right femoral medial healing corner fracture (white arrow), medial subperiosteal bone formation (arrowhead), and proximal tibial bucket-handle fracture (black arrow), all consistent with CML; radiograph shows no signs of rickets. All eight radiologists correctly interpreted radiograph as showing CML with moderate or high confidence.

(C, D) a 4-month-old boy with knee classic metaphyseal lesions diagnosed with child abuse and with vitamin D deficiency (23.4 ng/mL). Child had multiple fractures other than knee CML, including multiple posterior rib fractures and fractures of the right fibula, left femur, and right first metatarsal. (C) Radiograph of proximal right lower extremity from skeletal survey. (D) Edited radiograph of the right knee shows distal right femoral medial healing corner fracture (white arrow), medial subperiosteal bone formation (arrowhead), and proximal tibial bucket-handle fracture (black arrow), all consistent with CML; radiograph shows no signs of rickets. All eight radiologists correctly interpreted radiograph as showing CML with moderate or high confidence.According to the findings, the radiologists reached interpretations of rickets and CMLs with substantial to almost perfect agreement. For moderate- or high-confidence interpretations for CML, sensitivity across the eight radiologists was 95.1%, specificity was 97%, and accuracy was 96%.

Other key findings included that children with CML were younger than children with rickets (3.9% vs. 65.7% >1 year old) and that rates of false-positive moderate- or high-confidence interpretations were 0.6% for CML and 1.6% for rickets. Only one child with CML and low vitamin D received an interpretation of combined CML and rickets, the authors found.

"Less- and more-experienced pediatric and nonpediatric radiologists had high diagnostic performance in differentiating rickets and CML, regardless of the presence of vitamin D deficiency, with few false-positive interpretations for these diagnoses," the researchers wrote.

Ultimately, distinctive radiographic findings have been described in the literature that are unique for both rickets and classic metaphyseal lesions. However, some medical-legal practitioners claim that the existing literature is incorrect, the authors wrote.

This is the first study to directly evaluate the diagnostic performance of radiologists in differentiating rickets and CML, and the findings counter fringe claims that rickets may be the cause of fractures in suspected child abuse cases, they wrote.

"This multicenter study confirms the presence of distinctive radiographic signs of rickets and CML and demonstrates that radiologists can reliably differentiate these two entities," the authors concluded.