While MRI is sensitive and specific for liver imaging, the time required for a thorough examination often means that radiologists opt for CT due to quicker results and fewer artifacts. But what if the usual 30-minute slot for MRI could be reduced to 10 minutes? Would that sway doctors to send patients to the MRI suite more often? Experts at today's session on making the dream of 10-minute MRI exams a reality believe that it would.

Halving the time needed for MRI would not only generate faster results for patients but also would allow for greater daily throughput, and key to cutting MRI exam time is reducing the number of sequences and making the existing sequence acquisition time faster, according to Dr. Thomas Lauenstein, chair of radiology at Evangelisches Hospital in Düsseldorf, Germany.

He suggests that the 10-minute protocol may be routine in as little as two to five years. His talk will focus on the possibilities for the short protocol in clinical scenarios, if results from ongoing studies on faster MRI support this trend.

Speaking to ECR Today ahead of the congress, he revealed that not all radiologists knew that liver sequences could be modified and acquired in less time or that there were significantly shorter sequences available on some new generation machines.

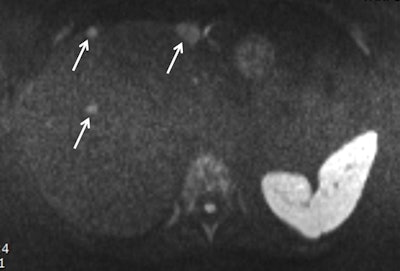

Obtained during a short protocol, this diffusion-weighted image shows a patient with conspicuous liver metastasis. The lesions are marked by arrows. Image courtesy of Dr. Thomas Lauenstein.

Obtained during a short protocol, this diffusion-weighted image shows a patient with conspicuous liver metastasis. The lesions are marked by arrows. Image courtesy of Dr. Thomas Lauenstein.During his presentation, he plans to provide a brief overview of available hardware, as well as physicist "tricks" for making single sequences faster. He will also cover how to use time more efficiently to maximize the data acquired.

One cornerstone of conventional liver MRI is delayed contrast-enhanced (CE) imaging. In a conventional protocol, acquisition of these sequences takes 15 seconds, which can be reduced to three to five seconds. The extra time gained between delay points should be used to acquire other data, such as T2-weighted imaging or diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), which conventionally is done before or after CE sequences.

DWI is another useful MRI technique for liver imaging. However, 20% to 30% of radiologists don't include it because they don't understand its benefits, Lauenstein noted.

"DWI has a two-minute acquisition time and provides similar information to T2-weighted imaging, meaning you can skip some T2 sequences," he said. "Importantly, DWI is an all-in-one sequence which provides different information."

He suggested that in a 10-minute protocol, all CE sequences could be avoided. DWI, T2, and T1 sequences should be prioritized instead. He also highlighted some of the pitfalls of the shorter MRI protocol for liver questions: While sensitivity remains high for any clinically relevant data, there will be some loss of specificity. When results from the short protocol are abnormal, the MRI scan will need to be repeated with standard sequences. This begs the question: Who should receive the short protocols and who gets the longer ones?

Short protocols are useful for negative prediction. However, when a pathology is suspected, as is usually the case in oncology, the radiologist will need more information. Leaving a patient in the scanner for a longer repeat scan would disrupt scheduling, and making the patient return for a second visit is not ideal, Lauenstein stated.

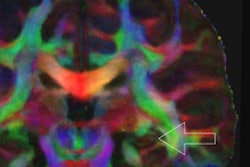

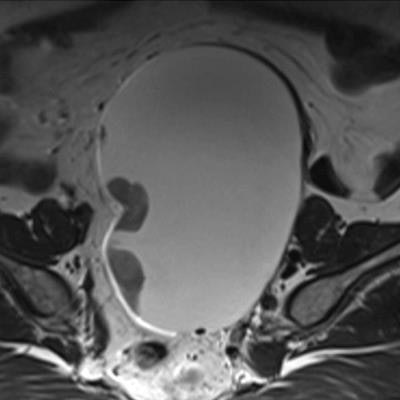

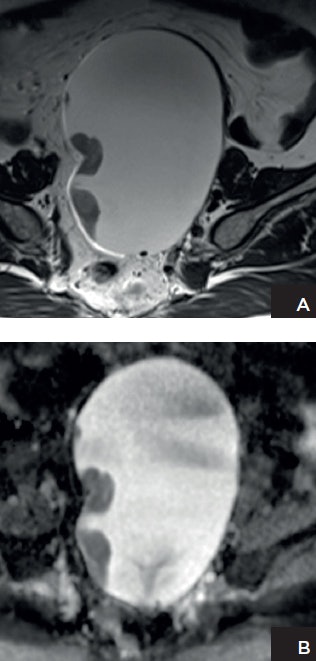

Patient with ovarian cancer. A: Axial T2-weighted high-resolution image shows a left adnexal lesion containing solid components. B: Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map shows marked restricted diffusion in the solid components, highly suggestive of malignancy. Histopathology confirmed the presence of stage 1 high-grade ovarian cancer. Images courtesy of Dr. Evis Sala, PhD.

Patient with ovarian cancer. A: Axial T2-weighted high-resolution image shows a left adnexal lesion containing solid components. B: Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map shows marked restricted diffusion in the solid components, highly suggestive of malignancy. Histopathology confirmed the presence of stage 1 high-grade ovarian cancer. Images courtesy of Dr. Evis Sala, PhD."It is difficult to quantify the percentage of cases for which you would need to repeat or prolong MRI or the cases that could be dismissed or diagnosed after 10 minutes. Successfully incorporating the short protocol depends on the type of practice and patient cohort," he said.

At Evangelisches Hospital, if there is a suspicion of liver pathology, then specificity is an essential factor, and patients undergo conventional liver MRI. For screening, general staging, exclusion of a liver lesion, or an MRI checkup, then the short protocol is preferred.

"Be familiar with the limitations of the 10-minute protocol and don't expect the same information as from the longer protocol, particularly in terms of specificity," he said, adding that patient history was vital in every case.

Dr. Evis Sala, PhD, a professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medicine and chief of the Body Imaging Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, intends to show how general radiologists can optimize MRI of the ovaries.

Tailored MRI protocols of around 20 minutes can answer specific clinical questions when adnexal lesions are indeterminate in ultrasound, she explained. Most of these indeterminate lesions that are sent to MRI for characterization will turn out to be benign lesions such as endometriomas and dermoid cysts. In these cases, there is no need for DWI or dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI because anatomical images are sufficient for an accurate diagnosis providing that image resolution is adequate. When evaluating the extent of endometriosis, for example, diffusion or contrast is only needed if there is suspicion of an arising tumor and these images would need to be reviewed before the examination is complete.

If the radiologist can supervise the MRI studies, especially in a small imaging center, then valuable imaging time can be saved, noted Sala, who is also a professor of oncological imaging at the University of Cambridge, U.K.

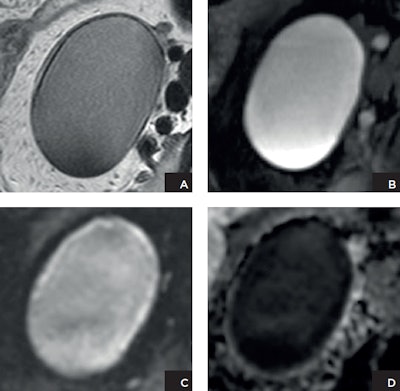

Patient with endometrioma. A: Axial T2-weighted high-resolution image shows a left adnexal lesion that demonstrates shading. The lesion is of high signal intensity on fat-suppressed T1-weighted image (B). Both the diffusion-weighted image (C) and the ADC map (D) demonstrate restricted diffusion. However, based on the anatomical images (A and B), the lesion can be confidently characterized as an endometrioma without any suspicious features for malignancy. This case highlights the pitfall of DWI as a nonspecific marker for cell density rather than tumor. Images courtesy of Dr. Evis Sala, PhD.

Patient with endometrioma. A: Axial T2-weighted high-resolution image shows a left adnexal lesion that demonstrates shading. The lesion is of high signal intensity on fat-suppressed T1-weighted image (B). Both the diffusion-weighted image (C) and the ADC map (D) demonstrate restricted diffusion. However, based on the anatomical images (A and B), the lesion can be confidently characterized as an endometrioma without any suspicious features for malignancy. This case highlights the pitfall of DWI as a nonspecific marker for cell density rather than tumor. Images courtesy of Dr. Evis Sala, PhD."It is imperative to establish the need for gadolinium administration. This also will help shorten the timing of the protocols," she told ECR Today, adding that at today's session she will also discuss the pitfalls of DWI, particularly in cases of suspected malignancy.

One major DWI pitfall is the correct use of restriction information. "No diffusion restriction indicates the presence of a benign lesion. Restricted diffusion is nonspecific. For example, benign lesions such as endometrioma and dermoids can show marked restricted diffusion," she said.

Originally published in ECR Today on 1 March 2018.

Copyright © 2018 European Society of Radiology