TORONTO -- Hearing aids may slow the metabolic decline that takes place in the brains of adults with mild cognitive impairment, according to research presented June 9 at the 2024 Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) annual meeting.

Natalie Quilala, an undergraduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles and colleagues presented evidence from F-18 FDG-PET scans that showed individuals with mild cognitive impairment who wore hearing aids had less cerebral metabolic decline than those with untreated hearing loss.

“These results suggest that while hearing loss can accelerate the decline in brain metabolism that occurs in people suffering from mild cognitive impairment, this acceleration may be largely mitigated through the use of hearing aids,” Quilala noted in a statement released by SNMMI.

The impact of hearing loss and use of hearing aids on the risk of developing dementia has been studied previously, yet few studies have compared changes in brain metabolism over time in subjects with hearing loss and subjects with hearing aids, she explained.

In this study, the group identified subjects with amnestic mild cognitive impairment who were screened for hearing impairments and had annual FDG-PET brain scans at baseline and for years after. They split the individuals into three groups, including those with untreated hearing loss and treated hearing loss/hearing aids (total n = 14), and a demographically matched group having no diagnosed hearing impairment (n = 17).

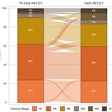

Over one year, the most significant differential metabolic decline occurred in the left superior frontal gyrus when comparing the control group against the untreated hearing loss group, according to the findings. The hearing aids group against the control group yielded a significant differential decline in left superior frontal gyrus as well (p = 0.02), while the hearing loss group declined 1.5 times faster than the hearing aids group, Quilala reported.

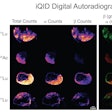

(A) Frontal cortical regions with below-normal metabolism (less than 5th percentile, displayed in color) at baseline, in subject with mild cognitive impairment and untreated hearing loss. (B) Frontal cortical regions with below-normal metabolism two years later. Brighter red colors correspond to more severely diminished metabolism. In contrast, the group of subjects using hearing aids did not undergo significant decline in any frontal cortical region over the same time period. Image courtesy of Natalie Quilala.

(A) Frontal cortical regions with below-normal metabolism (less than 5th percentile, displayed in color) at baseline, in subject with mild cognitive impairment and untreated hearing loss. (B) Frontal cortical regions with below-normal metabolism two years later. Brighter red colors correspond to more severely diminished metabolism. In contrast, the group of subjects using hearing aids did not undergo significant decline in any frontal cortical region over the same time period. Image courtesy of Natalie Quilala.

After two years, the untreated hearing loss group had significant declines against the control group in the right mid-frontal gyrus (p = 0.007), the right posterior inferior frontal gyrus (p = 0.01), and left inferior frontal gyrus (p = 0.04). In contrast, during the same period of time, the hearing aids group had no significant decline in metabolic rate in these or any other of the 47 brain regions examined.

“Strikingly, the hearing aid group did not experience significant annual metabolic decline in any frontal cortical region,” Quilala said.

There was no statistically significant difference in age or education between the hearing loss, hearing aids, and control groups. Moreover, the brain regions where the differences were detected were primarily in frontal cortical regions that are known to decline with normal aging, she added.

Ultimately, the results suggest that while hearing loss may accelerate the aging process occurring in cerebral metabolism, this acceleration may be ameliorated by the use of hearing aids, Quilala concluded.