CHICAGO - Serial MR imaging of West Nile virus (WNV) encephalitis in the brain of a man who died after contracting the illness shows that extensive disease may be present in such patients before it can be seen in MRI.

Dr. John Butman, a staff neuroradiologist at the Warren Grant Magnuson Clinical Center at the National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda, MD, said the 55-year-old man who was under treatment for leukemia fell ill with the viral infection and was hospitalized.

In a scientific presentation and subsequent news conference at this week's RSNA meeting, Butman discussed the man's case and compared it with that of another patient, a 55-year-old woman who had similar MR findings, but eventually recovered. The progression of disease is seen in cerebral MR images of the male patient's case, which are included in this article.

West Nile virus has spread rapidly since its introduction in the U.S. in 1999, Butman said. Only five states in the continental U.S. are free of outbreaks, and as of the end of November more than 4,000 cases of the disease had been reported, resulting in more than 200 deaths. The virus can be fatal in the elderly, or in those who are immunocompromised.

"West Nile virus is a member of the Flavivirus family, specifically of the Japanese encephalitis complex," Butman said. Both cases he reported on were discovered in the Washington, DC metropolitan area.

The 55-year-old male patient was undergoing immunoablative chemotherapy for leukemia. He presented with fever three weeks after chemotherapy undertaken in preparation for an allogenic transplant, Butman said. The patient's first neurologic symptoms developed on day 5 of the fever, and he subsequently underwent rapid neurologic decline.

Forty days after lapsing into a coma, the patient's life support was withdrawn and he succumbed. The WNV diagnosis was established by detection of viral RNA within a sample of the cerebrospinal fluid by polymerase chain reaction, Butman said.

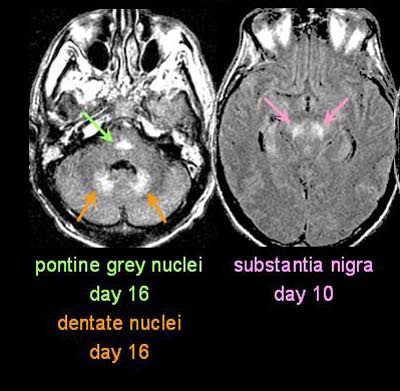

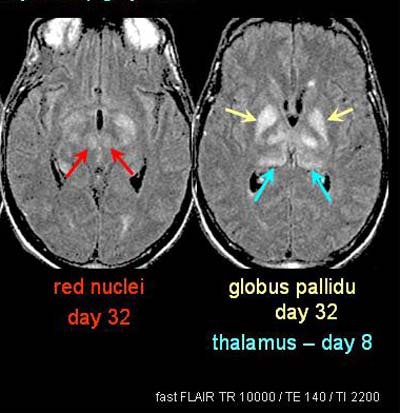

Above and below, a 55-year old man with West Nile virus encephalitis undergoes MRI imaging on day 32 of presentation with the disease. Note that all images are from day 32; other days indicated represent the days in which particular findings were first seen in previous MR studies. Fast FLAIR MR imaging protocol is included at bottom right. Images courtesy of Dr. John Butman.  |

MR imaging on day five on a GE Medical Systems scanner (Waukesha, WI) showed a normal series of images of the brain. By day 8, when the patient presented with dysarthria and dysphasia, the only MRI finding was a relatively subtle hyperintensity in the left thalamus, "which is not a call that can be made prospectively," Butman said.

On day 11 the patient's neurologic status worsened, he was intubated, and the lesion in the left thalamus is more clearly defined on MRI.

"You can also see there is bilateral hyperintensity in the substantia nigra," Butman said. "Again, because of its asymmetry it's a relatively difficult prospective finding to make."

Florid MR evidence of WNV encephalitis was finally visible on day 18, with MRI showing visible involvement of the deep gray nuclei and dentate nuclei, both bilaterally and symmetrically, Butman said.

"Involvement of the pontine gray nuclei and substantia nigra is much better demarcated at this point, and now there is progression throughout the thalamus with the involvement of the anterior and dorsoposterior nuclear groups," he said.

The patient's final MRI was performed on day 32, and in addition to the previously mentioned nuclear sites of involvement, showed a subtle bilateral hyperintensity in the red nuclei.

Spectroscopy on the same day showed a relatively normal spectrum in occipital gray matter, but normal N-acetyl aspartate, creatine and choline. In contrast, a voxel placed in the basal ganglia showed a nearly complete loss of N-acetyl aspartate, and relatively normal creatine and choline.

“To summarize our case, it's consistent with a neurotropic viral encephylitis, or a virus that specifically targets neurons,” Butman said. “This is demonstrated in the anatomic sites of involvement, as well as in the specific biochemical loss of N-acetyl aspartate. We saw no evidence of parenchymal or leptomeningeal enhancement throughout the course of disease, and diffusion-weighted MRI showed no evidence of ischemia.”

Butman and colleagues' experience contrasted somewhat with the 1999 WNV encephalitis outbreak in New York City. Researchers reported no gray matter lesions. Of the 13 MRIs performed in this series, 8 were described as normal or nonacute, and 5 showed evidence of meningitis with meningeal or periventricular enhancement.

Timing may account for the different experience in the New York City outbreak, Butman said. Without obvious MR findings until day 18, subtle lesions could have been missed, particularly in patients with existing disease. There may also be a lack of enhancement in immunocompromised patients, he said.

The Bethesda group's second case involved a 55-year-old woman with ovarian cancer, whose chemotherapy course was less toxic than that of the male patient. She presented with fevers and confusion, and deteriorated to coma within 48 hours. However, she recovered and was discharged on day 50 with neurologic deficits. Her WNV was imaged on a Picker MRI Scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA) and was diagnosed serologically with positive CSF and serum titers, Butman said.

The first MRI (day 2) showed a possible hyperintensity in the right thalamus, which became clear as her disease progressed, Butman said. Bilateral involvement of the substantia nigra was visualized subsequently, and by day 20, when she began to recover, some progression had been seen in enhancement of the red nuclei and the globus pallidus.

Thus, specific patterns of disease are seen in some viruses related to WNV, Butman said. The literature shows that Japanese encephalitis complex is a much more aggressive disease in which MRI is frequently abnormal, Butman said. In these cases the thalamus is the first and most common site of involvement, followed by midbrain involvement, and involvement of the substantia nigra and other deep-gray nuclei are reported.

In contrast, St. Louis encephalitis is much less aggressive disease, he said. The only MR abnormalities reported to date are in the substantia nigra.

Butman concluded that extensive disease may be present in patients with WNV encephalitis before it can be seen in MRI. However, he said, the modality is still very useful for ruling out the presence of other neurologic disease with overlapping symptoms.

Dr. Andrei Holodny, associate attending physician in neuropathology at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York said that anticancer treatments leading to the immunocompromised status of the two patients probably played a role in the progression of their disease.

"The initial MRI would rule out the possibility of a stroke, brain tumor or other viral encephalopathies such as those caused by herpes which look completely different and you can see very quickly," Holodny said. "Those studies would not rule out West Nile infection."

"The message of (the 55-year-old male's) case study," said Dr. Burton Drayer, chairman of radiology at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, New York, " is that if you have a puzzling disease and you don’t get an answer with MRI in the first few days, you have to persist until you get an answer. There are obviously changes that are going on; there is damage occurring but it may not be apparent for a week to 10 days."

Owing to the cost of MRI scans and the need to move an ill patient back and forth between critical care rooms and the MRI suite, doctors may be reluctant to order further tests when earlier scans at entry to the clinic or after a week have proven negative, Drayer said.

"It also shows that we still need even more sensitive devices to pick up the damage being done at an earlier stage."

By Eric Barnes and Edward Susman

AuntMinnie.com

staff and contributing writers

December

5, 2002

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com