The good news for people struck with sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is that MRI can readily detect the underlying cause of their problem. The bad news is that, as usual, payors are reluctant to authorize the expensive imaging exam. Two groups of head and neck specialists have come out for and against MR use in SNHL cases. A third group touts MRI's role in diagnosing sudden deafness in stroke patients.

MRI need not apply

First, otorhinolaryngologists from Charing Cross Hospital in London analyzed seven previously published MRI protocols for vestibular schwannoma, a leading cause of unilateral or asymmetric SNHL. Dr. Rupert Obholzer and colleagues reviewed 392 MRI scans performed at Charing Cross and at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, also in London. They concluded that establishing and applying a standard hearing test protocol could have reduced the number of MR scans.

Pure-tone audiograms (PTA) were collected for all patients with MR scans of the internal auditory meatus. Audiograms are graphs that depict hearing sensitivity. The degree of hearing loss is determined by measuring the hearing threshold, or decibel (dB) levels, at which a signal is just barely heard. Threshold frequencies are measured by hertz (Hz) and plotted on the audiogram.

"The (published) protocols considered a difference of either 15 or 20 dB significant ... we have also applied a 15 dB threshold in those whose better hearing ear had a mean PTA (250 Hz - 8 Hz) of ≤ 30 dB (considered a unilateral hearing loss) and a 20 dB threshold if the better mean was > 30 dB (asymmetric hearing loss)," the authors stated, describing what they called the "best protocol" (Journal of Laryngology & Otology, May 2004, Vol. 118:5, pp. 329-332).

Based on the MR results, there were 36 cases of vestibular schwannoma and 92 other causes of SNHL. Of the 36, 32 patients presented with asymmetrical SNHL, 19 of whom also had tinnitus.

The group analyzed the individual frequencies in these patients and found that a 15-dB difference at 2 kHz turned in a 91% sensitivity and a 60% specificity. They concluded that the "best protocol" was achieved by using a criterion of > 15 dB difference, at two adjacent frequencies, if the mean threshold in the better ear was ≤ 30 dB, and 20 dB if greater than 30 dB.

"The application of this protocol would have reduced the number of MRI internal auditory meatus scans requested from 392 to 218, saving 174 patients' scans," the group wrote. "MRI is relatively expensive ... and is associated with patient morbidity. It is therefore not suitable for universal screening."

Instead, they recommended reserving MR scans for patients in whom SNHL has already been defined by audiometry, in this case, a protocol that assesses interaural differences.

Deafness and AICA

The diagnosis of sudden deafness in acute ischemic stroke patients is an application with distinct advantages for MRI. In a recent case study, Korean neurologists reported on an 84-year-old woman who suddenly developed right-sided tinnitus, hearing loss, vertigo, and vomiting.

Audiometry and electronystagmography (test of involuntary eye movements) documented absent auditory and vestibular function on the right side. T2- and diffusion-weighted MR exams showed a tiny infarct in the right lateral inferior pontine tegmentum.

"Although sudden deafness occurs with anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) infarction, the deafness is usually associated with other brain stem or cerebellum signs," the authors wrote. But "AICA occlusion can cause sudden deafness and vertigo without brain stem or cerebellar signs," they added (Journal of the Neurological Sciences, July 15, 2004, Vol. 222:1-2, pp. 105-107).

In such cases, MR is pivotal as part of a full neurological workup. In a previous paper, the same authors, lead by Dr. Hyung Lee, Ph.D., examined the relationship between sudden deafness and AICA. Lee and co-authors are from various departments at Keimyung University School of Medicine in Daegu, South Korea. Dr. Robert Baloh from the University of California, Los Angeles also contributed to the research.

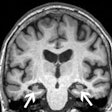

They looked at a dozen consecutive patients with unilateral AICA infarction as diagnosed by MRI. The imaging studies were performed on a 1.5-tesla scanner during the acute period after the onset of symptoms. Scanning was done in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. The protocol included T1-weighted imaging with short spin-echo pulse sequence, T2-weighted imaging with long spin-echo sequences, and single-shot, spin-echo-planar isotropic diffusion-weighted imaging. MR angiograms (MRA) also were performed.

PTA was done with a pure-tone average of > 25 dB regarded as indicative of hearing loss. Finally, the patients underwent auditory brain stem response (ABR) exams. The PTA detected unilateral SNHL in 10 patients and bilateral SNHL in one. The ABR showed normal, moderate, and mild hearing loss in all patients.

According to the results, only two patients had a complete AICA infarction. Six had facial hypalgesia, three had peripheral seventh-nerve palsy, and two patients had crossed sensory loss and Horner's syndrome, Lee's group reported (Stroke, December 2002, Vol. 33:12, pp. 2807-2812).

Based on the MRI and MRA findings, 11 patients were affected in the middle cerebellar peduncle. Eight patients had AICA territory infarction only. MRA showed stenosis of the lower and/or middle basilar artery, close to the origin of the AICA, in five patients.

The group detailed three cases in their study. In one, a 60-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension developed the sudden onset of vertigo and hearing loss on the left side along with other symptoms. PTA indicated a moderate SNHL (50 dB).

"Axial T2- and diffusion-weighted MRI of the brain showed a small infarct in the left ventrolateral pons ... brain MRA showed moderate stenosis of the middle third of the basilar artery," they wrote. When the patient did not improve with the first round of treatment, a follow-up MRI revealed new infarcts in the left middle cerebellar peduncle and left dorsolateral pons. After a second round of treatment and hospitalization, the patient's symptoms subsided, and the PTA showed that the hearing loss had improved (35 dB).

The authors concluded that hearing loss is a common finding in patients with AICA infarction, which requires a full diagnostic workup consisting of MRI, audiograms, and other hearing tests.

"Because the clinical presentation of AICA infarction may mimic more common vestibular disorders ... a detailed neurologic examination focused on additional brain stem signs ... should be performed," they wrote.

Hear hear for MRI

Head and neck surgeons from California compared MRI to auditory brain stem response (ABR), and found the former far superior for evaluating asymmetric SNHL. They went as far as to advocate abandoning ABR as a screening tool in these patients.

"The evaluation of asymmetric (SNHL) is essentially the search for a tumor in the area of the internal auditory canal (IAC)/cerebellopontine angle (CPA) or other more uncommon lesions of the temporal bone or brain," wrote lead author Dr. Ricardo Cueva from the Southern California Permanente Medical Group in San Diego (Laryngoscope, October 2004, Vol. 114:10, pp. 1686-1682).

While various SNHL tests have come and gone, the ABR test, which identifies waveform change patterns and absolute wave V latency between ears, came into vogue in the 1970s, and has been in use ever since.

However, "dramatic improvements in the radiologic diagnosis of IAC/CPA tumors in the mid to late 1980s would, in the 1990s, call into question the role ABR should take in the evaluation of asymmetric SNHL," he added. In particular, the success of gadolinium-enhanced MRI, with a sensitivity and specificity nearing 100%, made ABR seem particularly weak (Archives of Otolaryngology -- Head & Neck Surgery, October 1989, Vol. 115:10, pp. 1244-1277).

"Resistance to using MRI as the screening test of choice ... is primarily related to cost," Cueva stated. But using an inaccurate test, such as ABR, could be more expensive in the long run, the researchers added. "This study strives to provide a definitive determination of the accuracy of ABR as a screening test."

For this study, 300 patients with asymmetric SNHL were included (≥ 15 dB in two or more pure-tone thresholds). MRI scans were reviewed by a neuroradiologist for the presence or absence of retrocochlear pathology and other abnormalities. ABR, which was interpreted by audiologists, was considered abnormal if the IT5 interpeak latency was greater than 0.2 msec, and the absolute wave V latencies were abnormal as well, according to Cueva.

According to the MRI scans, 31 patients were found to have causative lesions for their SNHL (called index patients in the study), including vestibular schwannomas in the majority of cases (24).

"In addition to causative lesions, MRI identified a variety of significant incidental findings," Cueva wrote. "'Paranasal sinus disease' was the most common incidental finding," followed by cerebrovascular disease and asymptomatic tumors. Tinnitus was present in 70% of the patients with an abnormal MR.

In comparison, abnormal ABR results were found in 22 of the 31 patients. Nine were given a normal reading, although all but two had small vestibular schwannomas. ABR also failed to identify one glomus jugulare tumor and one ecstatic basilar artery. The sensitivity of ABR as a screening test was 71% and the sensitivity was 74%.

"The data indicates that nearly 10% of patients with asymmetric SNHL, by the study criteria, will have a causative lesion on MRI ... an additional 1% of patients are likely to be harboring significant incidental findings such as previously undiagnosed, asymptomatic tumors," Cueva wrote. "Such a patient would have a greater chance of suffering deafness, facial paralysis, and other cranial nerve injuries at the time of treatment."

While one MRI scan may be more costly than a single ABR test, missing a lesion or delaying diagnosis because of inadequate screening would be a heavy price to pay, he stated. Strategies for reducing MRI costs include a focused protocol resulting in a 15-minute scan time or using high-resolution, fast spin-echo MRI. Another option is to select patients for MRI screening based on duration of symptoms, patient age, and life expectancy. According to Cueva, relying solely on ABR will most likely require ongoing testing at an additional cost.

"There is no reason to continue using ABR to screen patients with asymmetric SNHL," Cueva concluded. "Use of the most sensitive/specific screening test available (MRI) would likely increase the ratio of smaller tumors suitable for treatment ... a reduction in treatment-related morbidity would be the most significant benefit of MRI screening."

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

November 26, 2004

Related Reading

Neuroimaging recommended in assessment of children with cerebral palsy, May 23, 2004

MRI, MRS piece together neurological damage in chemical solvent abusers, November 23, 2003

SPECT has a good ear for cochlear implants, August 16, 2001

Copyright © 2004 AuntMinnie.com