Coronary Artery Fistula:

Clinical:

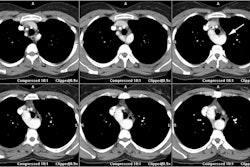

A coronary artery fistula is a rare (0.2-0.4% of congenital cardiac anomalies [2]) communication between the coronary artery and either a cardiac chamber, coronary sinus, superior vena cava, or pulmonary artery or pulmonary vein [1,2]. The lesion can be congenital or acquired- with the majority being of the congenital form [2]. The acquired lesion is most commonly seen following endocardial biopsy- especially in cardiac transplant patients. Other etiologies for acquired fistulas include coronary stent placement, CABG surgery, trauma, and chest irradiation [6].Congenital fistulous connections between the coronary system and a cardiac chamber appear to represent persistence of embryonic intratrabecular spaces and sinusoids [2]. There is no race or sex predilection [2]. A single fistula is occurs in 90% of cases (multiple fistulas are seen in 10-16% of cases) [6].

Most affected patients are asymptomatic [3] and the most common

clinical presentation is a continuous heart murmur [2]. Symptoms

depend on the location and size of the shunt as there is decreased

perfusion distal to the fistula (coronary steal phenomena

[3,7]. If symptoms develop most patients present later in

life with dyspnea and RV enlargement or dysfunction due to

progressive enlargement of the fistula and an increase in

left-to-right shunting [2]. Other presentations include fatigue,

orthopnea, chest pain, endocarditis (2-5%), arrhythmias, stokes,

angina/ischemia (secondary to a coronary steal phenomena [3]), MI,

and sudden cardiac death [2,3]. Associated cardiovascular

anomalies have been reported in 5-30% of cases [2]. On physicial

exam, there can be a loud heart murmur with a cresendo-decresendo

pattern that continues continously through systole and diastole

[6]. Patients with coronary fistulas are at an increase risk for

infective endocarditis (3-12% of patients) [6].

The right coronary artery is most commonly affected (50-60% of

cases) and the majority of symptomatic fistulas arise from the RCA

[1,2]. The fistula arises from LAD in 35-40% of cases, the left

circumflex in 5-20% of cases, and both the RCA and LCA in about 5%

[2,6]. Asymptomatic CAF's demonstrate a greater prevalence from

the LCA [2].

CAFs are classified into two categories- coronary cameral

fistulas which drain into the cardiac chamber (this is the most

common form), and coronary arteriovenous fistulas which drain to

the pulmonary or systemic circulation [6]. The fistula is usually

from the RCA to the RV (41-45% of cases); other sites of fistulous

communication include the RA (25-26% of cases), the pulmonary

artery (15-17% of cases), the coronary sinus (7%), the LA (5%),

the LV (3%), and the SVC (1%) [1,2,3]. The fistula drains into the

LA or LV in less than 10% of cases [1]. A fistula to the pulmonary

artery is most commonly from the LCA (84% of cases) and the

majority drain into the pulmonary trunk [6]. A fistula to the

coronary sinus is the CAF most frequently associated with CHF [6].

When the shunt leads to a right-sided cardiac chamber the

hemodynamics are similar to a left-to-right shunt (present in over

90% of cases) [1,2]. However, the shunt ratio is generally very

small and not detectable [2]. Myocardial perfusion can be

decreased due to a steal phenomena and can lead to myocardial

ischemia [1].

CAF's are unlikely to close spontaneously (there is only a 1-2% spontaneous closure rate) [5]. Asymptomatic CAF's can be monitored for change over time, but antiplatelet therapy and prophylactic antibiotic precautions against endocarditis are recommended [2,6]. Intervention is recommended for large fistulas or any fistula with symptoms [6]. Surgical ligation of the fistula is safe and effective with good results [2]. Transcatheter embolization and Amplatzer vascular occluders are non-surgical means of treatment for symptomatic lesions [2,5]. Indications for embolization include proximal location of the fistulous vessel, a single drain site, extra anatomic termination of the fistula away from the normal coronary arteries, older patient age, and absence of concurrent cardiac disorders that might require surgical intervention [2]. Surgery is preferred for a large CAF with high fistula flow, those with multiple communications/terminations or very tortuous pathways, significant aneurysm formation, or the presence of large vascular branches that could be accidentally embolized [2].

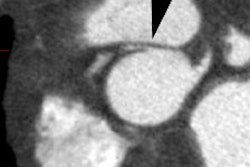

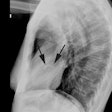

The involved vessel is usually dilated (secondary to increased blood flow) and tortuous [1].

REFERENCES:

(1) Radiographics 2006; Kim SY, et al. Coronary artery anomalies: classification and ECG-gated multi-detector row CT findings with angiographic correlation. 26: 317-334

(2) Radiographics 2009; Zenooz NA, et al. Coronary artery fistulas: CT findings. 29: 781-789

(3) J Nucl Cardiol 2009; Barone-Rochette G, et al. Combination or

anatomic and perfusion imaging for decision making in a

professional soccer player with a giant coronary artery to left

ventricle fistula. 16: 640-643

(4) Radiographics 2012; Shriki JE, et al. Identifying,

characterizing, and classifying congenital anomalies of the

coronary arteries. 32: 453-468

(5) Radiographics 2017; Agarwal PP, et al. Anomalous coronary

arteries that need intervention: review of pre- and postoperative

imaging appearances. 37: 740-757

(6) Radiographics 2018; Yun G, et al. Coronary artery fistulas:

pathophysiology, imaging findings, and management. 38: 688-703