Pulmonic Stenosis:

View cases of pulmonic stenosis

Clinical:

Pulmonic stenosis may be valvular, subvalvular, or supravalvular.

Supravalvular is the most common (60%) and the narrowing can occur anywhere from the pulmonary trunk to the segmental arteries [1]. Supravalvular pulmonic stenosis can be seen in association with Williams syndrome (abnormal facial appearance, mental retardation, and supravalvular aortic stenosis), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, or post-Rubella syndrome [1]. Supravalvular stenoses can be classified as one of four types: Type I involves a single stenosis of the main, right, or left pulmonary arteries without peripheral branch involvement. Type II involves stenosis at the bifurcation of the pulmonary trunk extending into the origins of the right and left pulmonary arteries, without branch involvement. Type III involves multiple stenosis of the peripheral pulmonary artery branhces without central involvement. Type IV involves a combination of central and peripheral pulmonary artery stenoses [1].

Pulmonary valvular stenosis is a congenital disorder in 95% of

cases [2]. In

most patients, pulmonic valvular stenosis (PVS) is an

isolated

anomaly that

does not present until adulthood. Pulmonic valvular stenosis (PVS)

can

also be associated

with congenital heart disease- particularly tetrology of Fallot,

rheumatic heart disease

(rare), infective endocarditis (tricuspid valve is concomitantly

infected in 50% of cases) [4], or carcinoid syndrome (variable

pulmonic valve involvement is

found in up to 50-60% of

patients and is secondary to vasoactive amines producing a

superficial

endocarditis- classically both the tricuspid and pulmonary valve

leaflets are involved [4]).

Patients with Noonan's syndrome (mental retardation, web neck, and

short stature) also

have an increased incidence of pulmonic valvular stenosis- found

in up

to 30% of cases.

Patients with mild to moderate PVS generally have few symptoms.

Symptoms occur at a variable valve gradient, but most patients

with a peak gradient of less than 25 mm Hg are usually

asymptomatic [4]. With

more severe stenosis

there is right ventricular hypertrophy and later enlargement and

failure. Patients with severe stenosis can present with dyspnea,

fatigue, chest pain, and decreased exercise tolerance [4].

A normal pulmonary valve area measures approximately 2 cm [3].

The most common type of pulmonic stenosis (40-60% of cases) is a

dome-shaped pulmonary valve [4]. It is characterized by a mobile

valve with two to four raphes and incomplete separation of the

valve cusps which creates a funnel shape with a small circular

orifice [4]. Dysplastic pulmonary valve is the second most common

type (20-30% of cases) [4]. It is associated with thickened,

immobile cusps and, in some cases, a hypoplastic

ventriculo-arterial junction [4]. Cauliflower-like myxomatous

thickening is limited to the free margin of the leaflets (the

proximal part of the leaflet is intact) [4]. The commissures are

not fused [4]. A bicuspid valve is rare (0.1% of hearts) [4].

X-ray:

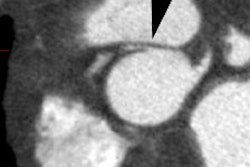

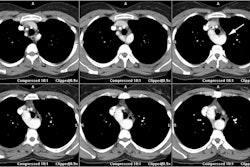

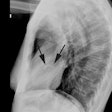

Post-stenotic dilatation of the main pulmonary artery is seen only in pulmonic valve stenosis. The degree of dilatation appears to be independent of the severity of the right ventricular outflow tract obstruction. A preferential 'jet-streaming' of blood across the stenotic pulmonic valve can result in asymmetric blood flow which is most commonly increased to the left lung (a classic finding in PVS). There will be associated asymmetric enlargement of the left pulmonary artery. Valve calcification is rare in PVS. MRI will demonstrate the turbulent jet as focal signal dropout in the left and main pulmonary artery segments, with normal laminar flow in the right pulmonary artery.

Patients with supra-valvular stenosis also typically have normal pulmonary blood flow on CXR. Patients with subvalvular, or infundibular, stenosis, however, typically have tetrology of Falot and therefore demonstrate decreased pulmonary blood flow.

REFERENCES:

(1) AJR 2000; Gamboa P, et al. Congenital multiple peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis (pulmonary branch stenosis or supravalvular pulmonary stenosis). 175: 856-857

(2) Radiographics 2009; Chen JJ, et al. CT angiography of the

cardiac valves: normal, diseased, and postoperative appearances.

29:

1393-1412

(3) J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2012; Buttan Ak, et al. Evaluation

of

valvular heart disease by cardiac computed tomography assessment.

6:

381-392

(4) Radiographics 2014; Saromi F, et al. CT and MR imaging of the pulmonary valve. 34: 51-71