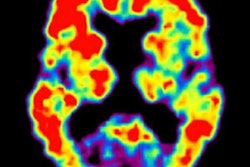

Can a person's progression from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer's disease be reliably predicted without PET imaging? A new study published online October 18 in the Journal of Nuclear Medicine lists several nonimaging methods that could offer a better prognosis than the modality.

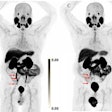

Researchers individually and collectively compared FDG- and florbetapir-PET with assessment tools such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), a functional activities questionnaire, and assessment of apolipoprotein E, a genetic indicator of Alzheimer's disease. While FDG outperformed florbetapir in predicting whether an MCI patient would develop Alzheimer's disease, a combination of the three nonimaging variables was even more successful in its prognostication.

"This [finding] was driven by the particularly high predictive value of the functional activity questionnaire, which is probably due to the fact the clinical decision on dementia is highly influenced by impairment of activities of daily living, which the questionnaire assesses," wrote the authors, led by doctoral student Ganna Blazhenets in the department of nuclear medicine at the University of Freiburg.

The current study follows recent research conducted by Blazhenets and colleagues that used a previously validated principal components analysis (PCA) with FDG-PET to determine whether a specific metabolic pattern is associated with conversion from MCI to Alzheimer's disease. The components included MMSE scores, functional cognition questionnaires, and other dementia-related indicators. Their hypothesis was proved with the combination of PCA and FDG-PET as achieving "high accuracy" in predicting an MCI patient's progression to Alzheimer's disease (JNM, June 2019, Vol. 60:6, pp. 837-843).

In the new study, the researchers expanded their exploration to amyloid-PET imaging with the radiopharmaceutical florbetapir (Amyvid, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals) and compared this approach against the predictive capabilities of FDG-PET and nonimaging variables. The comparisons involved 319 patients with MCI and for whom baseline FDG- and florbetapir-PET imaging was available, along with follow-up scans at six- and 12-month intervals for as long as 10 years. Subjects also were eligible for the study if their MMSE score was at least 24 points, which signals mild dementia, and showed no evidence of progression to Alzheimer's disease and/or reversion to MCI during follow-up.

Participants then were divided into two groups: 41 subjects (mean age, 72 ± 7 years) who advanced to Alzheimer's and 118 patients (mean age, 73 ± 8 years) who remained in their MCI condition. The researchers assessed each modality and nonimaging characteristics individually and collectively to determine the most effective methods of Alzheimer's prediction based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC), which measures the quality of one model against all others, with the lowest AIC score as the reference standard.

Combining information from all the available resources and the two modalities produced the best results with accuracy of 100% for predicting which patients would progress to Alzheimer's disease within five years. Individually, FDG-PET was significantly better at prognostication (AIC = 23.9) than florbetapir-PET (AIC = 25.9) (p < 0.001). Interestingly, the nonimaging combination was significantly better (AIC = 19.7) than the two modalities (p < 0.005).

The nonimaging variables also contributed greatly when added to PET imaging results. With FDG-PET, the AIC was reduced to 8.5, which was significantly better than 8.9 when combined with florbetapir-PET (p < 0.01).

Given the complementary prowess of FDG- and florbetapir-PET with the nonimaging variables, the study results should be "of great interest for clinical practice and clinical trials" and could aid in the counseling and treatment of MCI patients who eventually might have to deal with Alzheimer's disease, the authors wrote.