MR images of people who develop neurological complications from West Nile virus show that many of these patients experience brain damage years after the original infection, according to a new study presented on Tuesday at the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) annual meeting.

The 10-year study by researchers at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston tracks the progression of neurological deficits in people infected with West Nile virus. The researchers found evidence of cortical thinning, brain atrophy, and related cognitive impairment.

"It has been incredibly helpful following this population of patients. We have really learned a lot from them," said lead author Kristy Murray, PhD, from Baylor's National School of Tropical Medicine. "They are acutely ill, come in sick, and most of them have neurocognitive disease, meningitis, and encephalitis."

Persistent virus

Kristy Murray, PhD, from Baylor College of Medicine.

Kristy Murray, PhD, from Baylor College of Medicine.It's estimated that as many as 3 million people were exposed to the West Nile virus between 1999 and 2010, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has attributed more than 2,000 deaths to the infection. Previous research by Murray and colleagues suggests the death rate may be much higher.

The virus is spread by the common house mosquito and birds, and it has been found in every state of the U.S. except Hawaii and Alaska. Disease prevention experts advocate the use of mosquito repellent to reduce the risk, but it's a Herculean task.

"It is a huge effort that is undertaken every single year to do surveillance for mosquitoes," Murray said. "Unfortunately, the mosquito that carries the virus is prevalent throughout the whole country and into Canada."

Symptoms of West Nile virus typically begin to appear three to 15 days after the mosquito bite; however, approximately 80% of those infected do not develop any symptoms. Unfortunately, there is still no vaccine for humans, although there is one available for horses.

"Sadly, there is no treatment. That is most frustrating, especially when you see patients come in so ill," Murray said. "I get on my soapbox constantly about needing a vaccine. It amazes me that this is an infection that occurs year after year and severely impacts these patients' lives, and we don't have a vaccine."

Longitudinal study

The roots of the 10-year study date back to 2002, when the researchers began to track 262 people in the Houston area who were infected with the West Nile virus. Of the 262 subjects, 117 participated in follow-up neurologic and neurocognitive evaluations, with 30 (26%) receiving MRI scans to look for cortical thinning and regional atrophy. The subjects were also given the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) to measure cognitive decline or improvement.

Among the 177 people, 57 (49%) had some type of abnormal finding on their neurological exam. The most common abnormalities were decreased strength (30 patients, 26%), abnormal reflexes (16 patients, 14%), and tremors (12 patients, 10%). Interestingly, seven people (12%) diagnosed with neurological deficits never noticed any symptoms at all; their infection was detected during a routine screening test for blood donors.

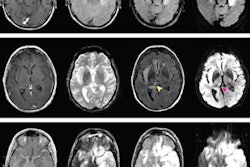

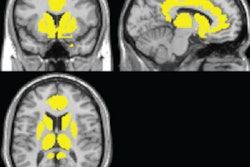

The MR images revealed significant cortical thinning in both the left and right hemispheres, primarily in the frontal and limbic lobes, compared with control subjects. In addition, the researchers found significant regional atrophy in the cerebellum, brain stem, thalamus, putamen, and globus pallidus.

"MRI helped us to target specific areas of the brain where we are seeing abnormal findings," Murray said. "It did not surprise us too much that we were seeing clinically that the subjects had a lot of cognitive deficits; some of them had hypoxia."

Cognitive changes

There was a 22% overall rate of impairment on the RBANS test, with 36 people (31%) presenting with immediate memory issues and 29 (25%) cases of delayed memory decline.

The researchers also found that approximately 70% of people with encephalitis never returned to their baseline health status, with a person's status at the two-year mark being particularly crucial.

"Looking at what happens over time, if they are going to have any chance of recovery back to their baseline status, it will occur within the first two years after their infection," Murray said. "What we find is that when they hit that two-year mark, if they have not recovered at that point, they are not going to [recover]. It plateaus out completely at that time."

In terms of future research, Murray and colleagues hope to conduct functional MRI studies to better understand what is happening in the brain and learn more about the role of the blood-brain barrier relative to the West Nile virus.

"We know that with West Nile disease, during the acute phase of the illness, the permeability of the blood-brain barrier is impacted by the virus itself and inflammation occurs because of the infection," she said. "The question is: Is that something that is persistent? Does it have a permanent impact to the blood-brain barrier during the acute phase of illness, or does it recover?"