Researchers from France have used 3D MRI to visualize changes to the shape of the fetal brain and skull during the second stage of labor. The images revealed that fetal heads may experience greater stress than previously imagined, according to an article published online on May 15 in PLOS One.

The capacity of a fetus' head to change shape during the second stage of labor, or fetal head molding, is well known but hardly ever examined with medical imaging. Having a better understanding of this process could facilitate childbirth and help clinicians determine the need of an otherwise healthy patient to undergo a Cesarean delivery (C-section), noted first author Dr. Olivier Ami from the University of Clermont Auvergne and colleagues.

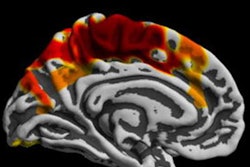

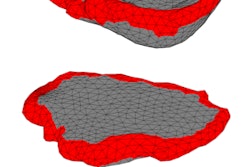

In the prospective study, Ami and colleagues acquired open-field 1-tesla MRI scans of 27 pregnant women before labor; seven of the women were scanned again during the second stage of labor (no more than 10 minutes before beginning expulsive efforts). Then the researchers transformed the MRI scans into finite element 3D reconstructions using proprietary 3D imaging software (Predibirth).

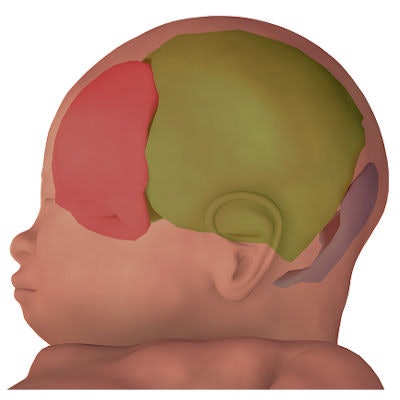

Examining these 3D reconstructions, the researchers found that all seven of the infants experienced considerable fetal head molding with slight differences in terms of which skull bones overlapped the most. Yet only two of the infants maintained a cone-shaped, or "sugarloaf," skull on clinical exam after birth.

Fetal head molding was most prominent on the anterior-posterior axis of the skull, as the group expected. Though the largest change in size between pre- and postpartum fetal skull shapes occurred in the fronto-occipital diameter (p = 0.035).

3D finite element reconstruction of the cranial bones before labor and during the second stage of labor. Image courtesy of Dr. Olivier Ami.

3D finite element reconstruction of the cranial bones before labor and during the second stage of labor. Image courtesy of Dr. Olivier Ami."During vaginal delivery, the fetal brain shape undergoes deformation to varying degrees depending on the degree of overlap of the skull bones," Ami said in a statement. "Fetal skull molding is no more visible in most newborns after birth. Some skulls accept the deformation (compliance) and allow [for] an easy delivery, while others do not deform easily (noncompliance)."

Despite normal pregnancies, two of the patients had to undergo a C-section because the heads of the fetuses turned out to be too large for vaginal delivery. These fetuses were among the three with the greatest degree of fetal head molding. For one of these cases, conventional MRI revealed that the fetal head was not ideally positioned for vaginal delivery even though a clinical exam suggested that the head was in the appropriate location.

Collectively, the 3D MR images showed that the fetal head may undergo significant deformation as it crosses the birth canal, which could negatively affect a child's condition at birth, according to Ami and colleagues.

"These MRI findings suggest that the fetus is subjected to greater stress than previously thought, which could explain the high incidence of asymptomatic brain hemorrhages and retinal hemorrhages found after normal vaginal delivery," the authors wrote.

The concept of normal birth does not currently consider the effect that variations in typical fetal head molding might have on a child's well-being. In the future, it may be necessary to take into account the extent to which the skull and brain change during labor when characterizing a child's birth, they concluded.