MRI scans can detect signs of excess iron accumulation in individuals who are genetically predisposed toward the condition, says an August 1 study in JAMA Neurology. What's more, males with this condition are also at higher risk of movement disorders.

Hereditary hemochromatosis is the most prevalent genetic disorder in Europe, affecting one in 300 non-Hispanic white people; it can lead to "iron overload," or the buildup of excessive iron in organs in the body. Iron overload can put individuals at risk of liver disease and diabetes, but its role in disorders of the central nervous system is still under debate.

The main treatment for hereditary hemochromatosis is phlebotomy, which if started early, can reduce adverse clinical effects, according to a research team led by first author Robert Loughnan, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego. Women are believed to be at lower risk of disease as they expel excess iron through menstruation and pregnancy, the group wrote.

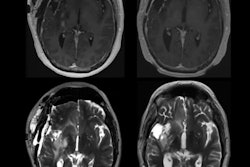

In the current study, Loughnan et al wanted to explore whether MRI could detect signs of hereditary hemochromatosis in the brain in individuals who were genetically predisposed to the condition. Next, they wanted to analyze whether these individuals experienced any neurological deficits and abnormalities.

The group started with a database of individuals from the UK Biobank project, a study of over 488,000 individuals recruited between 2006 and 2010. The team then identified those who had a particular genetic mutation, homozygote for p.C282Y, that put them at risk of hereditary hemochromatosis.

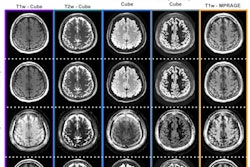

Loughnan et al further refined this cohort by selecting the individuals who had received MRI scans. They focused on two types of MRI protocols that are sensitive to iron accumulation, T2-weighted imaging, and T2*/R2* scanning.

They ended up with a study population of 836 people. Of these, in one group 154 people were positive for the genetic mutation and received T2-weighted MRI scans, with 595 controls. In a second group, there were 165 individuals positive for the mutation who received T2*/R2* scans and 671 controls.

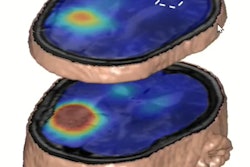

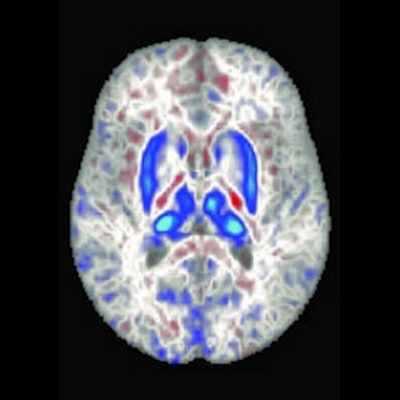

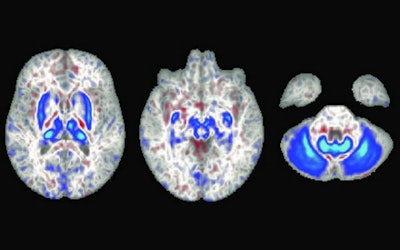

In these brain scans, blue areas indicate regions with iron accumulation in individuals with two copies of the hemochromatosis risk gene. These regions also play a role in movement. Image courtesy of University of California, San Diego.

In these brain scans, blue areas indicate regions with iron accumulation in individuals with two copies of the hemochromatosis risk gene. These regions also play a role in movement. Image courtesy of University of California, San Diego.The researchers found individuals with the homozygote for p.C282Y mutation had lower T2-weighted and T2* intensities in the brain regions related to motor control, a finding that is consistent with higher iron deposition in these areas. The imaging associations they discovered are consistent with a class of disorders called neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA), a condition in which genetic mutations lead to iron buildup in the basal ganglia, which in turn can lead to movement disorders.

"This iron deposition is believed to lead to oxidative damage of these brain regions, impairing their function and resulting in movement deficits," Loughnan et al wrote. "Hemochromatosis has traditionally not been included as a cause of NBIA."

To analyze the prevalence of movement or central nervous system disorders in people with the homozygote for p.C282Y mutation, researchers compared prevalence between men and women, and by type of disorder. The risk for males was higher than that for females, with men being at highest risk of movement disorders, with an odds ratio of 1.8. No statistically significant association was found between the mutation and disorders in women.

| Risk of movement disorders for individuals with mutation homozygote for p.C282Y | ||

| Type of disorder | Odds ratio | p-value |

| All movement and central nervous system disorders | 1.29 | p = 0.008 |

| Movement disorders | 1.46 | p = 0.007 |

| Other disorders of nervous system | 1.19 | p = 0.17 |

| Men -- All movement and central nervous system disorders | 1.57 | p < 0.001 |

| Men -- Movement disorders | 1.8 | p = 0.001 |

| Men -- Other disorders of nervous system | 1.39 | p = 0.049 |

The authors concluded that their study finds that neuroimaging with MRI can detect evidence of brain pathology in people with the homozygote for p.C282Y mutation even before symptoms appear.

"The convergence of our neuroimaging and genetic associations on movement-related circuits of the brain and movement disorders suggests that p.C282Y homozygosity may lead to brain pathology even in subclinical [hereditary hemochromatosis] cases," the researchers wrote.