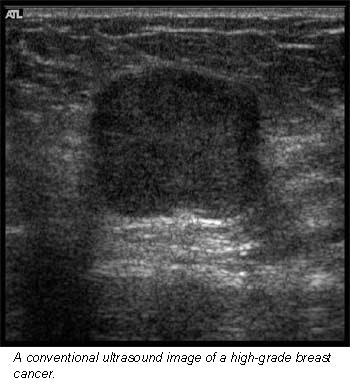

Compound ultrasound is better than conventional ultrasound when it comes to imaging breast masses, according to a pair of studies presented at the 2001 American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine meeting in Orlando, FL.

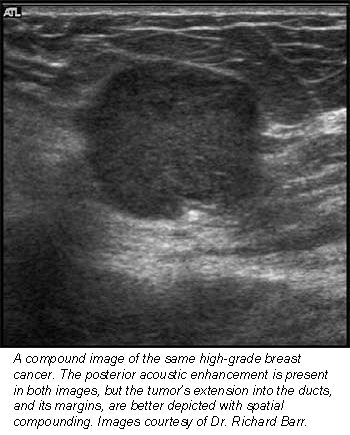

The studies represent the first clinical shakedown of the two-year-old technology, so-named because it fuses, or compounds, nine simultaneous scans taken from nine angles into a single image. More angles means less noise and clutter, as well as a sharper depiction of small breast-mass margins, explained Dr. Richard Barr, director of ultrasound and breast imaging at St. Elizabeth’s Health Care Center in Youngstown, OH.

In short, these advantages combine to improve radiologists’ confidence in diagnosing many lesions, he said. A classic example is a simple cyst, which, when imaged from only one angle as in conventional ultrasound, often has poorly defined margins that make diagnosis difficult.

"The sound beams deflect off the cyst's walls, making it hard to see," Barr said. "But if you image the cyst from different angles, and add these images up, you get a nice continuous border."

For the past two years, Barr has used the SonoCT real-time compound imaging technology, which is Bothell, WA-based ATL Ultrasound’s latest upgrade to its High Definition Imaging (HDI) series ultrasound scanners. The compound ultrasound market received another player at the 2000 RSNA meeting, when Siemens Medical Solutions of Iselin, NJ, introduced SieClear, a spatial compound upgrade to its Elegra system.

Hoping to ascertain the clinical worth of this new technology, Barr evaluated 100 breast lesions with both conventional and compound imaging. All 200 images were then read both randomly and side-by-side, in which both images of the same lesion were compared.

In the random analysis, viewers rated 91% of the compound images excellent in terms of margin definition, as well as near-field, lesion, and anatomic details. In the comparative analysis, compound ultrasound rated similar to conventional ultrasound in 82% of patients in depicting near-field detail and small structures such as ducts. And it rated better than conventional ultrasound in all patients for margin and lesion definition, as well as reduced speckle.

|

This last advantage -- less noise and clutter -- allows radiologists to examine minute structures like never before, Barr said. With conventional ultrasound, more patients had to be re-scanned or aspirated to determine if a mass was a tumor.

|

"Now, we can see if a tumor has advanced into a duct," Barr said. "Sometimes, these things are very small, and only with compound imaging can you tell if something is clutter noise or if it’s real."

Barr did find, however, that compound imaging lagged behind conventional ultrasound in shadowing and through-transmission. As he explained, shadowing occurs when sound waves hit a dense mass, such as a calcification. In these cases, the sound waves don’t penetrate and instead bounce back, leaving a black, shadowy area on the scan. This mark appears crisp on a conventional scan, but is unfortunately diluted in a compound image, he said.

Likewise, through-transmission occurs in less dense masses such as cysts. Sound waves easily pass through these liquid-filled lesions, resulting in a cyst-shaped bright spot on the scan. Again, these areas appear less crisp on a compound image.

Fortunately, Barr can toggle between conventional and compound imaging with the push of a button, so he can easily use standard imaging when shadowing and through-transmission problems arise, he said.

In a second study, researchers at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia used both conventional ultrasound and SonoCT to image 500 women undergoing ultrasound follow-up for suspicious clinical or mammographic exams. Of the 50 solid masses detected, the compound images bested conventional ultrasound in all categories, including margin definition, depiction of micro-calcifications, and minimizing shadowing from attenuating masses.

Despite compound imaging’s promise, the upgrade’s newness and price tag will likely limit its utilization in the near future, Barr said. And, as with any new technology, there’s an adjustment period. A radiologist examining his or her first compound scan might find the image too smooth or blurry, he said. But this first impression is short-lived, he said.

"When you get used to compounding, it’s tough to go back to standard images, because you realize how much clutter they have," he said.

By Dan KrotzAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

May 9, 2001

Related Reading

US compound imaging offers more breast lesion detail than traditional sonography, May 1, 2001

Click here to post your comments about this story. Please include the headline of the article in your message.

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com