Looking to accelerate its path to market, ultrasound developer InnerVision Medical Technologies has begun to search for a corporate partner to license its version of synthetic aperture technology. The company believes the technology produces a big boost in ultrasound resolution, particularly in scans of obese patients.

Founded in 2002, InnerVision has been developing multielement synthetic aperture imaging as a means of improving the resolution of ultrasound scanners, making them more versatile and clinically useful. In the past several years, several ultrasound industry veterans have joined the company as part of the effort.

One of them is Bhaskar Ramamurthy, PhD, who worked for ultrasound pioneer Acuson in the 1990s. He stayed with the company after it was acquired by Siemens Healthcare in 2000, eventually becoming director of ultrasound engineering before leaving the company in 2005.

Ramamurthy was drawn to InnerVision after seeing a demonstration of its technology that impressed him with its resolution and clarity. Ramamurthy joined InnerVision in 2009 and led the effort to fine-tune the technology, overcoming technical roadblocks that had delayed its development effort.

What is multielement synthetic aperture imaging? It's an adaption to ultrasound of synthetic aperture imaging, which was first conceived for radar systems in the 1950s. But applying the technology to ultrasound proved to be more difficult, according to Ramamurthy and InnerVision chairman Michael Broadfoot.

Traditional ultrasound scanners produce a transmit beam with a point of focus around which the image quality tends to be best. To improve image quality through additional planes, some scanners also place multiple foci along the direction of the transmit beam.

However, this approach has limitations, according to Ramamurthy. You can only add a discrete number of foci, and each time a foci is added, it requires an additional transmission of beam energy. This reduces the scanner's frame rate -- and thus its ability to keep up with motion, such as a sonographer's moving hand or a dynamic process in the body.

InnerVision's multielement synthetic aperture technology dispenses with focus beams, using what the company calls divergent beams. The diverging transmit beams illuminate a large portion of the area being imaged, Ramamurthy said.

In addition, InnerVision's technology both digitizes and stores the ultrasound energy that bounces off structures in the body and returns to the transducer elements. Conventional ultrasound scanners digitize this data but do not store it, he said.

For InnerVision, a breakthrough was dispensing with the traditional approach in ultrasound of transmitting the ultrasound beam on one element and receiving off multiple elements, which limits the penetration of the beam into the patient. Instead, the company's technology transmits and receives off multiple elements. It's this innovation -- and how InnerVision "choreographs" the sound waves transmitting energy -- that is key to the company's technology, Ramamurthy said.

Targeting the high end

Rather than target low-end or midrange ultrasound, InnerVision has set its sights high, preferring to compare its technology to the best super-premium systems from major ultrasound vendors.

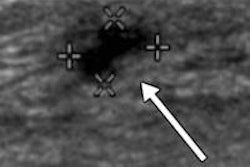

The firm has also picked the toughest patients: obese individuals for whom ultrasound has difficulty. In clinical validation studies, the InnerVision technology has been able to demonstrate anatomical structures deep in the body in patients with body mass indexes as high as 66. By showing its expertise in these patients, InnerVision should be able to excel in any other area, the company believes.

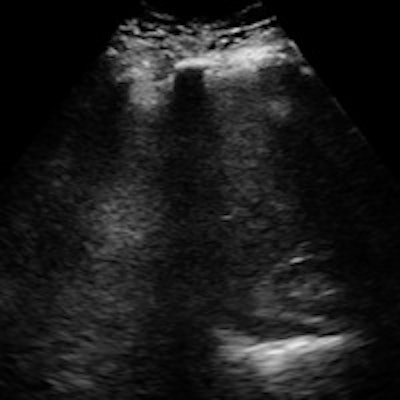

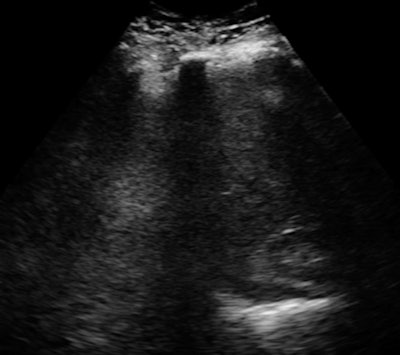

The upper pole of the kidney and the posterior diaphragm are clearly visible with the InnerVision system at an image depth of 300 mm. Premium-performance conventional systems routinely exhibit loss of penetration, detail, and visibility when imaging deep structures, especially in individuals with high BMIs, according to the company. Image courtesy of InnerVision.

The upper pole of the kidney and the posterior diaphragm are clearly visible with the InnerVision system at an image depth of 300 mm. Premium-performance conventional systems routinely exhibit loss of penetration, detail, and visibility when imaging deep structures, especially in individuals with high BMIs, according to the company. Image courtesy of InnerVision."Ultrasound has a saying: If you win in the belly, you win everywhere," Ramamurthy said.

Patient penetration is great, but success in ultrasound also requires market penetration. That has become increasingly difficult for small firms now that the era of independent ultrasound vendors such as Acuson and ATL is long over. To that end, InnerVision is now looking for partners to commercialize multielement synthetic aperture imaging, Broadfoot said.

"From our perspective, we are a collective together for a vision as a science team," Broadfoot said. "This technology deserves to be in the hands of parties that can really accelerate it."

He would like to see InnerVision find a corporate partner that can license the technology and either incorporate it into its own product line, or refine InnerVision's work and sell it as a complete scanner.

Broadfoot believes that InnerVision's technology could help revitalize ultrasound in a way that hasn't been seen since the independent companies dominated the landscape. Conventional ultrasound has reached a technology plateau in terms of image quality improvements, he said, and that has dissuaded the multimodality vendors from making further big investments in their ultrasound divisions.

If ultrasound can reclaim its status as a leader in high-quality imaging, it could change the diagnostic algorithm for many disease states, in which ultrasound serves as a gatekeeper to other modalities. For example, what if ultrasound was sufficient to use on its own?

"Because it is so much less expensive, you won't have to go to other modalities," Broadfoot said. "That is the role in the big picture that this kind of technology can drive."