Using ultrasound to monitor fetal heart rates can take up a lot of time for labor and delivery nurses, according to research published January 13 in Nursing for Women's Health.

A team led by Anne Fox from Virtua Memorial Hospital in New Jersey found that manipulating ultrasound transducers and repositioning patients take up about a third of the average work shift for labor and delivery nurses.

"Understanding the amount of time nurses spend at the bedside and the aids used for this purpose may provide a better understanding of the work of labor and delivery nurses," Fox and colleagues said.

Part of a maternity nurse's job is to continuously assess the health of the mother and fetus during delivery. This includes monitoring the fetal heart rate, which must be performed by a registered nurse.

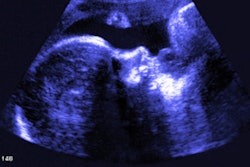

While this can be done by periodically listening to the fetal heartbeat, fetuses who are at higher risk for complications need electronic fetal monitoring. This is done by using a bedside monitor attached by cables to an ultrasonic transducer that's placed onto the expectant mother's abdomen to monitor fetal heart rate.

However, researchers said electronic fetal monitoring has been increasing in use over the last five decades.

"In fact ... health care providers and pregnant individuals have come to expect electronic fetal monitoring as a commonly used practice, even in low-risk pregnancies," the study authors wrote.

This constant recording, however, means time taken is taken away from nurses to provide education and emotional support to families in labor. Previous research suggests that nurses are not satisfied with current monitoring technology.

Little research has been done on how much time labor and delivery nurses spend on electronic fetal monitoring, including how they accomplish it and the financial implications of costs surrounding the time needed for monitoring and aids that nurses use.

"Understanding the amount of time nurses spend at the bedside and the aids used for this purpose may provide a better understanding of the work of labor and delivery nurses," Fox and colleagues wrote.

The researchers wanted to describe the time and effort such nurses put into continuous fetal heart monitoring. They looked at data from 134 nurses who participated in a survey.

The team found that 50% of nurses reported spending one to two hours repositioning an individual, while 48.9% reported spending one to two hours per 12-hour shift manipulating the ultrasound transducer. This means up to one-third of nurses' shifts were spent continuously working on electronic fetal monitoring, including working with ultrasound transducers.

Fox and colleagues also found that more than 133 of the 134 nurses reported using aids, with the most popular ones being supplemental monitoring equipment. This includes extra fetal monitor straps or improvised aids such as washcloths.

The study authors said these results may have implications for nurse staffing in labor and birth settings, and that future research should compare aids with different monitoring systems in patients in situations in which fetal heart monitoring is challenging. They also called for a financial analysis to find out the cost-effectiveness of using aids for continuous monitoring compared to electronic systems.

"Our results suggest that there is dissatisfaction among nurses with current electronic fetal monitoring technology and that device limitations should be addressed to ensure the accuracy of fetal monitoring while enabling labor and delivery nurses to focus more time on the individual and less on the monitor," the researchers added.