BERLIN - The potential of using computer-aided detection (CAD) as a diagnostic and clinical support tool in medicine has just begun to be discovered and commercially developed. Presentations at the two days of special sessions on breast, thoracic, colon, and liver CAD at the 2005 Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery (CARS) meeting revealed that discovery and utilization are just the tip of the iceberg of possibilities, as Heinz U. Lemke, Ph.D., the organizer of CARS for the past 20 years, noted in his presentation at the opening ceremony.

CARS positions itself as the venue for innovation, idea creation, and debate, and nowhere was this more apparent than in a freewheeling "Clinical Needs and Technical Requirements for Development of Practical CAD Systems" panel discussion. The mandate to participants was to be outspoken and controversial. The panelists did not disappoint.

Kunio Doi, Ph.D., and Dr. Robert Schmidt, noted pioneers in breast CAD research at the University of Chicago, co-chaired the panel. They assembled outspoken, in-the-trenches radiologists and researchers Dr. Stamatia Destounis from the Elizabeth Wende Breast Clinic in Rochester, NY; Dr. Fiona Gilbert from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland; and Dr. W. D. Kaiser of Friedrich Schiller University in Jena, Germany.

The panel also included leading industry representatives Carl Evertsz from MeVis BreastCare, A. Gupta from Siemens Medical Solutions, Julian Marshall from R2 Technology, and PACS and CAD research pioneer Dr. Matthew Freedman from the Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, DC.

The discussion focused primarily on CAD systems for mammography. Since its commercial introduction, CAD systems have significantly improved. A body of published research validates their use in identifying a higher percentage of early cancers. Yet global adoption in healthcare facilities performing mammograms is estimated to be only 15% to 20%. The majority of users are in the U.S., where financial reimbursement is provided by the U.S. government and most insurance payors.

The difficulty of detecting early symptoms of breast cancer spurred CAD's development and vendor investment of millions of dollars. Interpretation of mammography images requires extraordinary concentration by a radiologist searching for difficult-to-visualize cancers in a statistical average of five out of every 1,000 women. Even with the most experienced mammographers, reading mammograms can be stressful and fatiguing.

For this reason alone, a second review is advocated. "In our experience, a second reader will pick up 10% of the cancers overlooked by the first reader," Gilbert said. Double reading is mandatory in the U.K., which officially estimates that cancer detection is increased by 9% to 15% with this requirement, she noted.

However, double reading doubles radiologist workload and increases examination cost. Furthermore, workload is increasing, as the generation of post-World War II baby boomers ages and begins to require mammograms. Adding to the pressure is a decrease in the number of radiologists who elect to read mammograms or specialize in the field. All these factors have made the need for accurate, efficient CAD support more acute.

Schmidt started the panel discussion by saying, "After I realized the value of this machine in the late 1980s, I thought that (mammography) CAD would be a no-brainer. The technology would take off like a rocket. Yet it hasn't."

He posed the following questions:

- Why is CAD not achieving a higher utilization rate?

- Can CAD today do some of the analysis in lieu of a radiologist or eliminate the need for one with a portion of exams in the future?

- What is needed and may be realistically achievable in the next generation or two of commercial CAD systems?

Mammography CAD systems are perceived as inefficient, identifying more suspicious areas than a radiologist wants to investigate or has time to do so. Schmidt pointed out that while the average 60 marks per image generated by the beta unit evaluated by the University of Chicago were excessive and totally impractical, he felt that the number of marks displayed in today's systems was realistic. CAD systems can identify more cancers than radiologists, producing false positives at only 1.5%. "Isn't this good enough?" he asked.

Apparently not. Freedman, who is working with lung CAD, described research conducted to determine at what thresholds a viewer would review all displayed marks, evaluate only some of them, or become overwhelmed by the quantity of marks and dismiss selective review altogether. Research tests revealed that threshold acceptance levels are highly individualistic, and emotional reactions at the individual levels of information overload varied markedly. It is industry's challenge to produce CAD systems that identify enough suspicious areas that may be overlooked, but not so many as to slow down or frustrate the reader, according to Freedman.

This challenge is considerable. The addition of selectable threshold levels by a user in new CAD systems elicited animated discussion. How does a radiologist lowering a threshold determine the point at which he or she overlooks cancerous systems, and so also does the CAD? How is this monitored for quality control? Are low-sensitivity readers who need CAD assistance the most more or less prone to inappropriately adjusting threshold levels?

How can CAD be designed to reduce the variability of radiologists? Destounis noted that mammographers can be categorized in various types -- for example, high cancer detection with high recall/low recall, or low cancer detection with high/low recall. "Double reading can balance these performance differences, which have real consequences on patient stress and generating/reducing additional healthcare costs," she said.

One of the needs of CAD is to correctly identify where it can provide the greatest utility based on the reading styles and recommendations of individual radiologists. Destounis also noted that at her clinic, the impact of CAD to modify results varied markedly among her colleagues with equal experience.

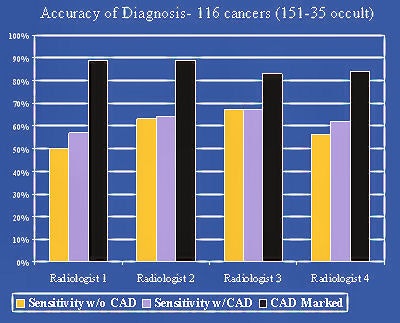

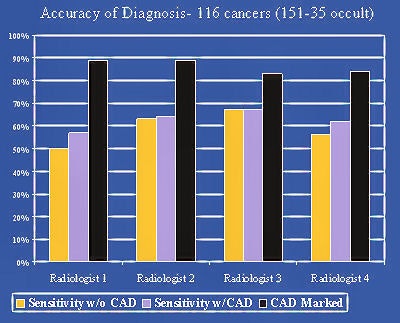

|

| Sensitivity with and without CAD and sensitivity potential if radiologist prompted to call back other marked cancers. Chart courtesy of Dr. Stamatia Destounis, Elizabeth Wende Breast Clinic in Rochester, NY. |

Destounis pointed out that for some, spending the time to evaluate CAD marks provided no benefit to improving diagnosis. Could a system be designed to evaluate what it needed to show to an individual user, based upon an analysis of that user's findings without CAD assistance?

Kaiser emphasized that CAD results need to be more consistent with respect to analyzing analog films. He conducted an experiment in which the same set of films was processed on three different days. To his surprise, although the identification of cancers remained consistent, the marks for microcalcifications varied considerably. Only 18% of the films produced consistent CAD notations for each of the three processings. While this problem has been resolved for digital mammography analysis, the majority of the world's healthcare facilities produce film, Kaiser said.

A recommendation was made that integrated digital mammography/CAD systems should add the ability to rank exams by level of complexity. In facilities where radiologists read in batch mode, the exams would be presented in order of complexity. This could combat fatigue and late afternoon workflow pressures.

Associating a probability level to symbols for both mass and calcification was the greatest priority recommended to industry. If CAD algorithms could evaluate the probability of cancer for each mark, this capability would increase radiologist review efficiency, enable department CAD review protocols to be defined, and make quality peer review easier.

Right now, the use of CAD is an individual decision. This would change if cancer probabilities could be ranked, either with differentiated symbols or percentages noted with the marks. Such a feature might convince governments to mandate mammography CAD use, Gilbert said. She also surmised that CAD would be better accepted by European radiologists who need to maintain their workflow pace to read between 100-200 exams an hour.

The topic of whether CAD could replace a radiologist was vigorously discussed as well. The consensus of opinion was that future products might be accurate enough to independently evaluate the least difficult exams, such as those of patients with fatty breasts and no demographic proclivity to cancer.

Marshall of R2 Technology pointed out that because today's systems have a 98% accuracy level of identifying microcalcifications, many of his company's customers rely on CAD to identify these, and do not independently try to do so themselves. "We don't think it is the right thing to do. But this may be an example of algorithm performance that has achieved its objective. It is realistic to think that at some point CAD will do some analysis better than an individual radiologist. Do radiologists achieve a 98% level of microcalcification identification?" he asked.

The consensus was "No." Mammography CAD had achieved at least one milestone.

By Cynthia Keen

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

June 28, 2005

Related Reading

CAD segmentation for mammo acceptable -- except in heterogeneously dense breasts, April 26, 2005

CAD offers promising second opinion, even in dense breasts, March 15, 2005

CAD may unmask unsuspected cancers in diagnostic mammo, October 27, 2004

New software version cuts false-positives in breast CAD, March 10, 2004

Computer analysis does not improve mammographic detection of breast cancer, February 4, 2004

Copyright © 2005 AuntMinnie.com