Full-field digital mammography (FFDM) performs better than film-screen mammography (FSM) in detecting ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive cancer -- without increasing "overdiagnosis," a concern long highlighted by breast cancer screening critics, according to a new study in Radiology.

Dutch researchers compared film-screen mammography to digital mammography in a population-based breast cancer screening program, focusing particularly on the clinical relevance of detected cancers. They found no evidence that FDDM results in an increase in the detection of low-grade DCIS lesions, which would indicate possible overdiagnosis; instead, digital mammography increased the detection of high-grade DCIS (Radiology, October 2, 2012).

Critics of breast cancer screening often argue that high detection rates of DCIS represent overdiagnosis, claiming that many cases are biologically unimportant, wrote lead author Dr. Adriana Bluekens of the National Expert and Training Centre for Breast Cancer Screening in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and colleagues. But such criticism is unfounded without data about the characteristics of the detected lesions, since DCIS can range from indolent lesions to aggressively ones.

"There is an ongoing debate about overdiagnosis in screening," contributing author Dr. Gerard den Heeten told AuntMinnie.com via email. "Our study was part of our quality control and monitoring of the Dutch program [which screens] almost 1 million women per year. [Increased detection of less relevant lesions due to digital mammography] could potentially influence the balance between harms and benefits of a screening program."

As the Netherlands was transitioning from conventional to digital mammography in its screening program, three pilot studies were established in 2003 and 2004 to test FFDM's quality and how its use might affect the program. Bluekens' group used data from all three of these pilot studies for this research, including almost 2 million screening exams performed between 2003 and 2007 at three screening centers.

If both modalities were available at the same screening location, women were assigned to FFDM or FSM depending on the availability of the units when the women arrived at the screening center, although those who had previously had digital mammography were always offered FFDM, the authors wrote.

Of the total exams included in the study, 1,045,978 were film-screen exams (87.3%) and 152,515 were digital exams (12.7%). Recall was indicated in 18,896 cases.

Breast cancer was diagnosed in 6,410 women, with FFDM showing a detection rate per 1,000 women of 6.8, compared with 5.6 for FSM. The difference in detection for subsequent screening examinations was also in favor of digital mammography, with rates of 5.2 and 6.1 per 1,000 women for FSM and FFDM, respectively, according to the group.

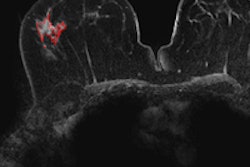

Digital mammography found more high-grade DCIS lesions than FSM: 58.5% compared with 50.5%, respectively, Bluekens' team found.

The distribution of the histopathologic differentiation grades for DCIS and invasive cancer were similar for both modalities, the authors wrote. However, digital mammography detected more high-grade DCIS lesions at subsequent exams, 90% of which manifested as microcalcifications.

"We were surprised by the fact that [digital mammography did not find more low-grade lesions] but rather more high-grade lesions -- although this finding was not statistically significant," den Heeten told AuntMinnie.com. "Most of us will agree that the detection of high-grade DCIS is a relevant finding because if [these cancers continue to develop] they will emerge as high-grade, invasive ductal carcinomas."

Also, as expected, the initial recall rate was higher with digital mammography, at 4.4%, than with FSM, at 2.6%. The higher recall rate led to lower positive predictive values of recall in initial and subsequent screening examinations, according to the group.

But the recall rates may have been slightly overestimated because calculations were based on the complete study period, including the first months after the introduction of digital mammography -- which are typically characterized by disproportionately high rates of recall, Bluekens and colleagues wrote.

Do the study findings address concerns that mammography is overused? It depends, den Heeten said.

"For those who are worried about an extra boost in overdiagnosis because of [digital mammography's] ability to find more calcifications, our result might be reassuring -- and could stimulate them to find out if this is also the case in their own screening program," he told AuntMinnie.com.

The researchers cautioned that the results are based on analysis of data from the Dutch screening program, with its focus on balancing the rates of detection, recall, and false positives; numbers from U.S. screening programs, which focus more on high detection rates, would likely be different.

"These differences should be kept in mind when comparing results among the Dutch, U.S., and other screening programs," the team wrote.

The aim of screening is not to detect cancer as such -- but to prevent tumor progression to disseminating, metastatic cancers, according to Bluekens and colleagues. Therefore, depending on the biologic potential of cancers, early detection is only beneficial as long as it contributes to a decrease in cancer mortality and morbidity: All other diagnoses of malignancies could be termed overdiagnosis.

"Overdiagnosis is an inevitable side effect of every screening program," they wrote. "In breast cancer screening, it is accepted because the benefits clearly outweigh the harms. However, overdiagnosis continues to be cited by critics of screening who assume that with the introduction of digital mammography in screening even more clinically unimportant cancers will be detected. ... [Our study] suggests that presumed overdiagnosis does not increase with the use of digital mammography in breast cancer screening programs."