It used to be that 2D mammography was the only breast cancer screening game in town. Breast imagers now have more weapons in their arsenal, but when is the best time to use which technology? Fortunately, a new screening algorithm can help imagers decide how to personalize their approach to screening.

That's why personalized breast cancer screening isn't just a fanciful idea, but rather an imperative, according to Dr. Joseph Russo, section chief of women's imaging at St. Luke's University Health Network in Bethlehem, PA. And personalized screening means taking a multimodality approach.

Dr. Joseph Russo from St. Luke's University Health Network.

Dr. Joseph Russo from St. Luke's University Health Network."Trying to fit all of our patients under the umbrella of 2D mammography is outdated," Russo told AuntMinnie.com. "Now that there are alternatives, it's incumbent on us to tailor screening regimens in order to maximize our chance of finding clinically significant cancers."

Which women need what technology?

Russo and his department have developed a screening algorithm that helps determine which women need what kind of screening, while also providing patients and referring physicians with clear guidelines, which he presented recently at the National Consortium of Breast Centers meeting (NCoBC 2016) in Las Vegas. In addition to 2D mammography, St. Luke's uses tools such as automated breast ultrasound (ABUS), digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), and MRI as adjuncts to screening.

Russo's algorithm takes patient risk and breast tissue density into account, he said; risk is gauged using the Tyrer-Cuzick lifetime risk model. There are three imaging paths based on cancer risk:

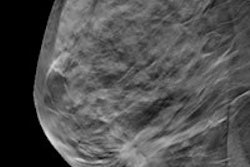

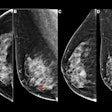

- Average risk (15% lifetime risk or less): Women without dense tissue go to mammography, while those with dense tissue go to tomosynthesis and perhaps automated breast ultrasound.

- Intermediate risk (15%-20%): Women without dense tissue go to tomosynthesis, while those with dense tissue go to tomosynthesis and automated breast ultrasound.

- High risk (more than 20%): Women with and without dense tissue go to mammography plus MRI (with ABUS as an alternative for those who can't tolerate MRI).

How does this protocol differ from generally accepted practice? It performs risk assessment on every patient, and breast ultrasound is used more frequently, according to Russo.

"The biggest strategic difference [in our protocol] is a more liberal use of automated breast ultrasound," he said. "I find ABUS to be especially useful, not only in dense breast patients, but in patients who are both dense and cystic. ABUS allows the radiologist to discount a background of complicated cysts and focus on suspicious findings such as architectural distortion and potentially solid masses."

Education is key

The protocol won't work as well if patients and referring physicians don't understand that screening is getting more complicated because it needs to get more complicated, Russo said. Education on this point is crucial, and it can happen through the web or social media, clinician grand rounds, and technologists and breast health nurses. The radiology department at St. Luke's actually sends a graphic of its screening algorithm to referring physicians.

"We spent a great amount of time disseminating dense breast talking points to physicians, educating them at departmental staff meetings and grand rounds," he said. "And I often field calls from clinicians requesting an appropriate screening regimen based on a specific patient's risk and density."

St. Luke's screening protocol pushes its radiologists to see the various screening modalities not individually but as interconnected, according to Russo.

"Our hope is that this process will allow us to increase our cancer detection rates, specifically in women at high risk and those with dense tissue, while minimizing unnecessary imaging for women who don't fall into these categories."

Seeing clearly

There's another benefit to the multimodality approach to screening: It helps breast imagers gain more confidence in their 2D mammography interpretations, Russo said.

"3D mammography and ABUS expose radiologists to an increasing amount of what are overwhelmingly benign lesions, the kind that are routinely called back on 2D mammography," he said. "As radiologists develop the confidence not to recall women for these findings that are increasingly seen on dense-breast imaging adjuncts, that will translate into increased confidence on 2D mammography -- which should improve our callback and cancer detection rates as well as decrease unnecessary biopsies."

In any case, the one-size-fits-all approach to breast cancer screening just doesn't work anymore, Russo said.

"The key component to our algorithm is a divergence from mammography dogma: If you have breasts, get a mammogram," he said. "What's replacing this framework is one of personalized medicine, which is the future not only of breast screening, but health screening."