Standardized identification of the initial method of detection of breast cancer is feasible across different practice sites, according to a study published March 11 in the Journal of the American College of Radiology.

The study results could offer important data about the impact of screening in the U.S., wrote a team led by Sujata Ghate, MD, of Duke University in Durham, NC.

"Prospective collection of method of detection data may help determine how screening mammography and supplemental screening options (ultrasound, MRI) contribute to reduction of mortality and morbidity from breast cancers," the group noted.

The American College of Radiology (ACR), the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), and the American Cancer Society (ACS) all agree that screening mammography starting at age 40 saves the most lives, but disagreement continues over the risks and benefits of screening, the best age at which women should start, and how often they should be screened, the group explained.

"[These] disagreements have produced conflicting recommendations that confuse patients and providers and miss opportunities to save lives," it wrote.

Some countries support population-wide breast cancer screening programs and track the initial method of detection, whether screening mammography or clinical examination. This tracking can link outcomes "directly to method of detection, to understand and adapt breast cancer care to evolving technologies and populations," the group noted, adding that U.S. databases that include breast cancer cases have not included method of detection information.

"Without patient-specific data on initial method of detection, national organizations … when examining the impact of screening, still turn to models based on historic data and variable assumptions that are subject to bias," it wrote.

Ghate and colleagues investigated the feasibility of collecting patient-specific method of breast cancer detection for inclusion into reports and registries via a study that assessed the rate of assignment of breast cancer method of detection in four health systems in different U.S. geographical areas (Mid-Atlantic, South, Midwest, Pacific Northwest).

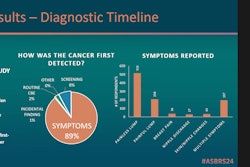

The research included 2,328 patients who had received a new breast cancer diagnosis between July 2020 and June 2022; radiologists at each of the four sites were oriented as to how to assign breast cancer method of detection on diagnostic breast imaging reports with a final categorization of BI-RADS 4 or 5, and Ghate and colleagues reviewed patient charts to determine the frequency and accuracy of method of detection assignment for all cases. Methods of detection included screening mammography in asymptomatic patients, patient or provider disease identification through self or clinical examination, and an alternative identification of disease (for example, incidental finding on CT imaging).

The team found that of the total number of patients included in the study, method of detection was assigned by the radiologist in 94% of cases, and retrospective review confirmed accurate assignment in 96% of these.

"Each of our diverse pilot sites used different radiology information software systems, specialist and generalist radiologists, academic and community facilities, and diverse dictation systems yet were able to enter an appropriate method of detection consistently and correctly, suggesting that widespread assignment of [method of detection] may be possible and successful," the team concluded.

The complete study can be found here.