VIENNA - The gap between reality and virtuality in liver imaging appears to be narrowing. Cutting-edge techniques based on new virtual reality technology are increasingly applied to clinical liver imaging and surgery.

At Friday's New Horizons session, attendees took a journey through time and space with the four expert speakers. The trip started with current applications of virtual liver models and multimodality imaging strategies with new contrast-enhanced liver studies and biomarkers, and moved on to the fusion of operating and radiology suites where MRI machines move on rails from one room to another.

Prof. Carlo Bartolozzi, chief of diagnostic and interventional radiology at the University of Pisa, Italy. All images provided by ESR.

Prof. Carlo Bartolozzi, chief of diagnostic and interventional radiology at the University of Pisa, Italy. All images provided by ESR.

The constantly evolving outlook for 3D tools in clinical situations looked limitless, as delegates were shown films of surgeons operating on patients accompanied by screens on which computer models intraoperatively facilitated surgery, and patients underwent procedures with their own imaging data projected onto their exposed flesh to map their organs.

"The liver is the litmus test for measuring our skills," said moderator Prof. Carlo Bartolozzi, chief of diagnostic and interventional radiology at the University of Pisa, Italy. "It is a fascinating organ that has unique functional and anatomic features with reserve and regeneration capabilities, complex vascularity, and (the ability to) experience a huge variety of diseases."

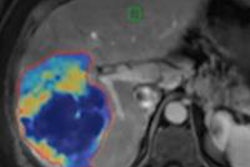

Imaging the liver has a direct impact on daily practice. It can characterize focal lesions, detect diffuse liver diseases, and guide interventional radiology, and it is fundamental for therapeutic decisions and evaluation of response. The challenge, though, is to learn how to image and display the liver and how to create virtual models and exploit these in clinical routine.

Current virtual reality components in use are impressive: the DICOM 3D image datasets produced by high-quality imaging equipment, as well as high-powered computer capabilities for image processing and presentation. Emerging now are key elements of the animation process, including medical images from 3D modalities and mathematical modeling, according to Prof. Lorenzo Martí-Bonmatí, professor of radiology at La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia, Spain.

Prof. Lorenzo Martí-Bonmatí, professor of radiology at La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia, Spain.

Prof. Lorenzo Martí-Bonmatí, professor of radiology at La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia, Spain.

"Moving to 3D is still a hot topic, but the transition is really happening through the incorporation into daily clinical practice of the visualization of organ properties on a 3D basis with physiological modeling computer simulations," he told ECR Today. "There are still challenges. The complexity of data and postprocessing validation, standardization, incorporation of these tools in PACS, and how to report and share images with clinicians; these issues need to be resolved."

Session objectives included pointers on how to image and display the real liver, reviewing new multiparametric and multimodality imaging strategies, becoming familiar with contrast-enhanced studies of the liver, and learning about liver biomarkers.

The development and integration of imaging biomarkers has added a new dimension to the traditional radiological workflow and meant that radiologists can benefit from quantitative structured reports to make their own diagnoses and report, in turn, to the clinician. Such regular use of imaging biomarkers depends on meeting the criteria of conceptual consistency, technical reproducibility, sensitivity, and specificity. The development and optimization of different imaging acquisition protocols and 3D data analyses would change clinical research and patient care scenarios, according to Martí-Bonmatí.

Prof. Davide Caramella, professor of radiology at the University of Pisa.

Prof. Davide Caramella, professor of radiology at the University of Pisa.

"A radiology department equipped with the ability to produce virtual models based on imaging will also benefit from improved relationships with the referring department and surgical colleagues," he added.

Image preparation is not only improving diagnosis due to optimized 3D display and multimodal integration, it is also providing quantitative data to guide interventions, according to Prof. Davide Caramella, professor of radiology at the University of Pisa, who addressed postprocessing and modeling at Friday's session.

"The exciting and magic data in postprocessing can be used for choosing and planning liver interventions such as transplantation or evaluating response to therapies," he said. "In a patient with large lung metastasis, the model of future tumor remnant was insufficient to ensure adequate functionality. After right lobe portal embolization, the CT was repeated after two months. At this point, the future tumor remnant model was judged to be sufficient."

In his talk on planning and simulation, Prof. Osman Ratib, chair of the department of radiology and head of the division of nuclear medicine at the University Hospital of Geneva, Switzerland, described a surgeon's preference to use reverse grayscale to plan surgery as being like a tree in winter. But the radiologist must take into account what the surgeon wants to see, according to Ratib.

Completing the session, future visions of patient care thrilled delegates as Prof. Nassir Navab, chair for computer-aided medical procedures, department of computer science, Technical University of Munich, talked about patient-specific intraoperative multimodal imaging and visualization.

Originally published in ECR Today March 3, 2012.

Copyright © 2012 European Society of Radiology