3D printing can influence strategy changes and improve surgical confidence when planning surgeries for complex cases of congenital heart disease (CHD), according to research published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

In an imaging vignette article, a team of researchers led by Dr. Dong Hyun Yang of the University of Ulsan College of Medicine in Seoul, Korea, detailed how 3D-printed models have led to a shift from palliative to corrective surgery for some patients at their institution with complex CHDs.

"For cases with unclear surgical plan following the review of conventional imaging, 3D printing is a helpful adjunct and can help guide appropriate surgical decision-making," the authors wrote.

3D printing can generate models of complex CHD, but the researchers have found limited evidence that the technology leads to modification of surgical procedures for the disease. As a result, they sought to review the impact of 3D-printed models at their hospital.

The heart team conference had screened 511 patients as potential subjects for 3D printing of their hearts between 2017 and 2019. At the conference, surgical strategies were divided into four categories: corrective (i.e., biventricular repair), equivocally corrective, equivocally palliative, and palliative (i.e., Fontan operation).

Of these, 40 (7.8%) received 3D printing of their hearts due to uncertainty of surgical strategy following multidisciplinary review of conventional imaging, according to the authors. Thirty (75%) of these cases involved a double-outlet right ventricle.

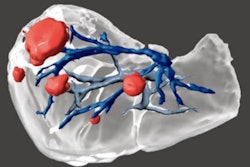

Two types of models were printed from preoperative CT scans: A cast model of the blood pool and an endocardial wall model for the endoluminary anatomy. The researchers noted that it took an average of 7 ± 2 days to receive the model from their 3D printing provider. The average cost was $1,297 ± 294. The final surgical plan was then confirmed at the heart team conference after review of the 3D heart model.

Prior to 3D printing, 26 (65%) of these cases were considered to be equivocally corrective and 14 (35%) of the cases were deemed to be equivocally palliative. After 3D printing, 5 (36%) of the 14 equivocally palliative cases were changed to corrective strategies and all of these cases received corrective surgery based on the 3D printing information, according to the researchers.

What's more, 27 (67.5%) of the 40 cases had their strategies modified to a more confident category after 3D printing. Eight cases had no change in their feasibility classification, according to the researchers.

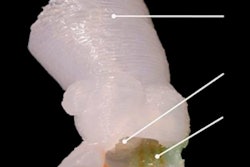

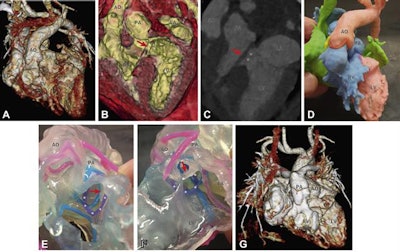

In their article, the researchers shared two specific cases in which 3D printing resulted in a change in surgical strategy, including a 4-month-old boy who had a double-outlet right ventricle with a subpulmonary ventricular septal defect. After reviewing the model, the surgical plan was successfully changed from an equivocally palliative strategy to a corrective strategy. The successful results of the operation were demonstrated on postoperative CT.

(A to C) CT images of a 4-month-old boy show a double-outlet right ventricle with a subpulmonary ventricular septal defect (asterisks). The aorta (AO) and approximately 70% of the pulmonary arterial trunk (PA) arise from the morphologically right ventricle (RV). The ventricular septal defect involves the uppermost part of the septum below the pulmonary valve. Noticeably, an abnormal papillary muscle (arrow) arises from the RV side of the ventricular septal defect margin and goes to the mitral valve, which is suggestive of the straddling mitral valve. Before 3D printing, the surgical strategy was equivocally palliative. (D) Blood pool and (E and F) endocardial wall modeling delineate the relevant anatomy, including the margin of the ventricular septal defect (asterisks on a purple ring), the pulmonary annulus (blue ring), and the abnormal papillary muscle (arrow). The surgical plan was changed to corrective after reviewing the 3D printout. (G) Postoperative CT shows the successful results of the arterial switch operation and the ventricular septal defect baffling. Images and caption courtesy of JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

(A to C) CT images of a 4-month-old boy show a double-outlet right ventricle with a subpulmonary ventricular septal defect (asterisks). The aorta (AO) and approximately 70% of the pulmonary arterial trunk (PA) arise from the morphologically right ventricle (RV). The ventricular septal defect involves the uppermost part of the septum below the pulmonary valve. Noticeably, an abnormal papillary muscle (arrow) arises from the RV side of the ventricular septal defect margin and goes to the mitral valve, which is suggestive of the straddling mitral valve. Before 3D printing, the surgical strategy was equivocally palliative. (D) Blood pool and (E and F) endocardial wall modeling delineate the relevant anatomy, including the margin of the ventricular septal defect (asterisks on a purple ring), the pulmonary annulus (blue ring), and the abnormal papillary muscle (arrow). The surgical plan was changed to corrective after reviewing the 3D printout. (G) Postoperative CT shows the successful results of the arterial switch operation and the ventricular septal defect baffling. Images and caption courtesy of JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.The second case involved a double-outlet right ventricle with a noncommitted ventricular septal defect related to a subpulmonary outflow tract in a 35-month-old boy. Prior to 3D printing, the surgery strategy was palliative, but the surgeons successfully changed to a corrective approach after reviewing the 3D model.