It's official: Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is no longer a research tool, and all radiologists should know how it works and the right way to analyze images in clinical settings. That's the view of expert speakers at today's session on abdominal DWI, which aims to evaluate the technical difficulties and clinical relevance of both qualitative and quantitative diffusion-weighted approaches in clinical practice. Delegates will also hear how small bowel DWI is edging ever nearer acceptance in routine application.

Dr. Luis Martí-Bonmatí, PhD, from Valencia, Spain.

Dr. Luis Martí-Bonmatí, PhD, from Valencia, Spain."DWI is a must in all the abdominal examinations. It is an extremely accurate technique for lesion depiction and lymph node assessment; its high accuracy for negative lymph node prediction is particularly useful," said session moderator Dr. Luis Martí-Bonmatí, PhD, chair of radiology and director of medical imaging at La Fe University and Polytechnic hospital in Valencia, Spain. "This technique is also crucial in the evaluation of lesion response to therapy, as different DW metrics are considered biomarkers of tumor cellularity. This means that we have a very early matrix of treatment effect and can quickly adjust therapy regimens accordingly."

However, some technical hurdles remain. The chief difficulties with regard to the clinical use of DW images are related to signal homogeneity, spatial resolution, large b-value option and number of b-values, he said. Signal intensity in DW images decreases when the b-values increase. Furthermore, fat suppression techniques and echo planar imaging (EPI) sequences are prone to artifacts and distortions, and spatial resolution is limited by the inherent low signal intensity and long acquisition times.

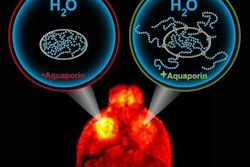

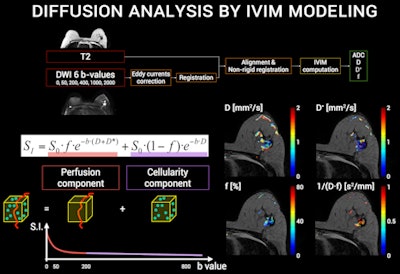

To solve these problems, a sequence with a robust fat suppression technique -- with a high signal-to-noise ratio, acquired with respiratory synchronization and with at least 6 b-values -- is needed to qualitatively evaluate restriction and depict lesions and at the same time measure the D, D* and F components of the intravoxel-incoherent-motion (IVIM) model.

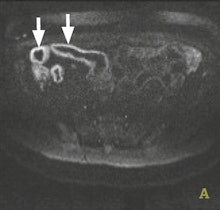

IVIM sequences can measure properties such as cellularity, perfusion, and vascular fraction, yielding qualitative and quantitative data. Images courtesy of Dr. Luis Martí-Bonmatí, PhD.

IVIM sequences can measure properties such as cellularity, perfusion, and vascular fraction, yielding qualitative and quantitative data. Images courtesy of Dr. Luis Martí-Bonmatí, PhD."Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) is simple and widely used but it is a bad matrix which introduces errors, due to the difference between centers and machines. ADC should be replaced with the IVIM matrix," Martí-Bonmatí said.

At present, this approach is chiefly undertaken by hospitals participating in clinical trials and in cancer research programs, but within a few years most hospitals will use this technique because high-quality sequences will be made available by vendors. General radiologists need to know the direction that DWI is taking, he noted.

"For a clinical radiologist who is only looking for qualitative data, 2 b-values are enough. But for quantitative measuring inside tissues, organs and cells and phenotying tumors, for assessing lymph nodes and for shedding light on early tumor response to treatment, then at least 6 b-values with IVIM sequences are required," Martí-Bonmatí said. "This requires more time for acquisition, so now is the time for vendors to design faster sequences so that images can be acquired in a shorter time and with higher spatial resolution."

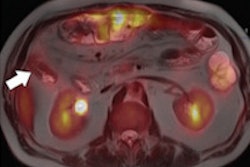

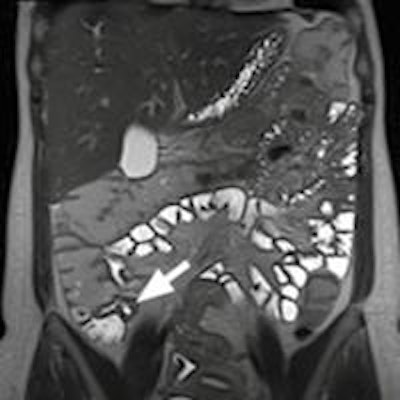

The application of DWI is well-established in helping to detect and characterize disease in the brain and liver, but it is relatively new in Crohn's disease. Key to management of this chronic relapsing disease of the bowel is differentiating between active inflammatory disease and chronic fibrosis because this helps determine whether the patient will be treated with immunosuppressive drugs or surgical resection.

Dr. Stuart Taylor from London.

Dr. Stuart Taylor from London.Gastrointestinal imaging specialists believe there is compelling evidence that bowel affected by Crohn's disease leads to abnormal DWI,and there is considerable interest in whether DWI can help aid both detection of affected bowel and differentiation of active disease from fibrosis, according to Dr. Stuart Taylor, consultant gastrointestinal radiologist and professor of medical imaging at University College London. He is concerned about how the inflammatory process affects the movement of water, yielding abnormal DWI signal.

"In theory the greater the inflammation, the more abnormal the DWI signal," he said in an interview ahead of the congress.

However, recent information correlating MRI with histopathological examination of surgical resection specimens suggests chronic fibrosis could affect DWI signal in a similar way as inflammation. This means that when there is a question about fibrosis, for example in longstanding disease or in patients who are still symptomatic after long drug treatments, DWI probably should not be used on its own for differentiation. Instead, the radiologist should deploy conventional T2 and contrast-enhanced sequences which can help differentiate active versus nonactive disease.

"In the literature, one suggested role for DWI is to replace enhanced sequences. However, we need further evidence that such replacement will not impact on the ability of the radiologist to distinguish whether there is predominantly inflammation (active disease) or fibrosis (nonactive disease)," said Taylor, stressing that such differentiation was fundamental to determining treatment pathways.

He envisages that high sensitivity of DWI for abnormal bowel will give it a role in initial staging of the small bowel in newly diagnosed patients. It will also be useful in established Crohn's disease cases for defining how active the disease is, and particularly for monitoring therapy response during treatment. Taylor reports particular use of DWI by pediatric radiologists as a sensitive, minimally invasive method to identify abnormal bowel in young children. In addition, DWI may replace sequences using intravenous contrast, particularly if detection of fibrosis is not the main clinical question.

"The question that now needs to be addressed is whether or not DWI should be a part of routine practice every time there is a suspicion of Crohn's disease, or if it should be reserved for selected cases, for example to monitor activity change during or after treatment, or in a newly diagnosed patient to establish the exact location of the disease," he noted.

The evidence will grow over the coming years, through retrospective and prospective studies, according to Taylor, who is currently conducting a trial to research whether DWI changes overall diagnosis compared to conventional sequences.

At the University College London, DWI is routinely used to diagnose and assess Crohn's disease, but he admits that the additional five to 10 minutes required, on top of an existing 20 to 30 minute procedure, represents a time increase of around 25%, and not all institutes may be willing to include it.

At today's session, ECR delegates will also learn how DWI state-of-the-art sequences can be standardized and optimized in clinical practice by using techniques like IVIM sequences to measure properties such as cellularity, perfusion, and vascular fraction, yielding qualitative and quantitative data.

Originally published in ECR Today on 3 March 2016.

Copyright © 2016 European Society of Radiology