Bronchiectasis:

View cases of bronchiectasis

Clinical:

Bronchiectasis describes an anatomical permanent abnormal

dilatation of the bronchi

which usually involves medium sized airways. Proximal bronchi with

more cartilagenous

support are less likely to dilate (an exception to this rule is

bronchiectasis which

occurs secondary to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. The

main clinical manifestation of bronchiectasis is chronic

productive cough [14]. Patients can also present with

recurrent respiratory infections or hemoptysis (50%) and

nonspecific symptoms such as general malaise and weight loss.

Bronchiectasis is bilateral in 50% of

cases. Treatment in most cases includes antibiotics for

superimposed infections, bronchodilators, chest physiotherapy, and

inhaled steroids, but the effectiveness of these agents in

preventing long-term decline is not fully supported [14]. Chronic

colonization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a poor

prognostic indicator [14].

An underlying cause for bronchiectasis is found in less than 40% of patients. Etiologies of bronchiectasis include:

- Post infectious: Infection is the most common cause of bronchiectasis, especially following childhood viral (especially adenovirus type 7) or mycoplasma infection. A history of childhood infection has been documented in up to 70% of patients with bronchiectasis [11]. Both primary and post-primary tuberculosis are also commonly associated with bronchiectasis (up to 27% of patients especially the upper lobes) [11]. This is most likely secondary to airway obstruction from adenopathy, and granulation tissue within the bronchi. Measles produces a profound inflammation of the bronchial walls, and was previously a major cause of bronchiectasis. Pertussis also produces a necrotizing bronchitis, but it's incidence has declined with immunization.

- Aspiration or inhalational injury (ammonia or sulfur dioxide inhalation).

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: Produces central, cystic bronchiectasis (See discussion ABPA)

- Congenital forms: Kartageners (dysmotile cilia syndrome), Cystic fibrosis, Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Yellow nail syndrome, Williams-Campbell syndrome, Marfans syndrome, or Chronic granulomatous disease of childhood.

- Chronic obstruction: Bronchiectasis frequently develops in areas that are chronically atelectatic (due to endobronchial obstruction) and this is probably a manifestation of chronic inflammation/infection. Foreign body obstruction primarily involves the right lower lobe, or posterior segment of the right upper lobe.

- Acute pneumonia: With acute pneumonia local bronchial dilatation is frequently identified, however, this phenomena is termed "reversible bronchiectasis". The bronchi may remain dilated for several months following the episode of infection, but will typically revert to their normal size. Because of this, it is advisable to wait at least 4 to 6 months following an acute pneumonia before evaluating a patient for bronchiectasis [1].

- HIV may be an etiologic cause of bronchiecatsis even in the absence of superinfection [2]

Types of bronchiectasis include:

1- Cylindric/Fusiform/Tubular: Cylindrical bronchiectasis produces "tram-lines" because the distal bronchus has the same lumen size as parent and extends to the lung periphery. This is the most common form of bronchiectasis [14]. It may occur secondary to infection, ciliary dyskinesia, or cystic fibrosis. Patients may have only mild symptoms such as a cough, with small amounts of sputum production [3]. On HRCT there are thick walled (smooth, not irregular) bronchi which extend into the peripheral 3 cm of the lung.

2- Saccular/Cystic: This is the most severe form of bronchiectasis. It is characterized by progressive dilatation of the bronchi toward the periphery which terminate in cytic cavities resembling balloons. The findings may resemble a cluster of cysts. Air-fluid levels within the massively dilated bronchi are seen frequently due to retained secretions, and are usually not seen in uncomplicated lung cysts. Remember, that in contrast to bronchiectasis, emphysematous bullae have no discernible walls.

3. Traction/ Varicose: Unlike most other causes of bronchiectasis, the airway changes are not caused by a primary insult to the airways themselves, but rather as a result of adjacent parenchymal fibrosis. In this form of bronchiectasis the bronchial walls are characteristically more irregular and may assume a beaded appearance when in the plane of section (resembling a "varicose" vein). Differentiation from cylindrical bronchiectasis is difficult when viewed in cross section.

X-ray:

CXR: Chest radiography is neither sensitive or specific for the diagnosis of bronchiectasis [10]. Non-specific findings such as peribronchial thickening, bronchial crowding, atelectasis, and persistent infiltrates are seen in up to 80-90% of cases [7]. However, other authors suggest a much lower incidence (0% to 50%) of radiographic abnormalities [8]. In one study, CXR had a sensitivity of only 37% for the detection of bronchiectasis [10]. Classic findings of bronchiectasis include parallel linear densities (tram-tracks) which represent the thickened walls of the dilated bronchus, and branching densities (gloved finger) which represent retained secretion or mucus within the dilated bronchi. When seen end-on, the bronchiectatic bronchi appear as ill-defined ring shadows. Compensatory hyperaeration of uninvolved segments of the ipsilateral lung can result in segmental obstructive emphysema.

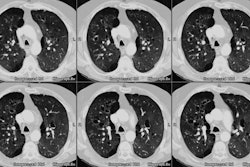

Computed tomography:

HRCT is presently the imaging modality of choice to evaluate for the presence of bronchiectasis. Scans are performed using 1 to 1.5 mm collimation at 10 mm intervals. Using a 20 degree cranial oblique scan will improve visualization of the bronchi along their long axis (especially in the lingula and middle lobes), but is usually not necessary. HRCT has been shown to have a sensitivity of 96-98% and a specificity of 93-99% in the detection of bronchiectasis; however, care must be exercised when making the diagnosis.

On HRCT, relating the size of the bronchus to the adjacent pulmonary artery has been the most widely used criterion for the detection of bronchiectasis. In patients with abnormal, dilated bronchi, the involved airways often appear much larger than the adjacent pulmonary artery branch on cross-section (the normal ratio can reach up to 1.3:1 - this finding is referred to as the "signet-ring" sign (ie: the internal bronchial diameter is larger than that of the adjacent pulmonary artery) [14]. Although the presence of bronchi larger than their adjacent artery is often assumed to indicate bronchiectasis, almost 20% of normal bronchi can have this appearance, and nearly 60% of normal subjects have at least one such bronchus. This is because the pulmonary artery size is not fixed and varies with physiologic changes in blood volume and local hypoxia [5,6,8]. Increased vessel caliber can be associated with left-to-right cardiac shunts [8] and pulmonary artery hypertension (central vessels). Any cause of underventilation will produce reflex bronchoconstriction and narrowing of the vessel caliber [8]. A bronchial to adjacent pulmonary artery ratio of greater than 1.5 is a more specific, but less sensitive for the diagnosis of bronchiectasis. Lack of bronchial tapering is probably the more accurate method for confirming the presence of bronchiectasis. Another indicator of bronchiectasis is the identification of bronchi less than 2 mm in diameter which are closer than 2 cm to the pleural surface- bronchi are not normally visible this far peripheral on HRCT. however, due to improved CT technology, normal bronchi may now be identified within 1 cm of the mediastinal pleura, but not the costal or paravertebral pleura [8].

Bronchial wall thickening is noted in the majority of patients with bronchiectasis. Assessment of bronchial wall thickening on HRCT is quite subjective [8]. Perivascular interstitial thickening (peribronchial cuffing) can also mimic bronchial wall thickening. Secretions within very small peripheral dilated bronchi can produce branching centrilobular densities or a tree-in-bud appearance [8]. Expiratory CT images in patients with bronchiectasis will often demonstrate a pattern of mosaic attenuation with areas of decreased and normal lung attenuation [8].

Enlarged bronchial arteries can be demonstrated in patients with bleeding bronchiectasis [9].

Occasionally, non-bronchial cystic pulmonary lesions can simulate bronchiectasis such as histiocytosis X [8], pneumocystis pneumonia [8], and tracheobronchial papillomatosis. Cardiac pulsations can produce a tram-line appearance to bronchi in the lingula and right middle lobe due to motion [8]. Motion artifact can be reduced by the use of ECG-triggering for image acquisition [12].

Multidetector helical CT imaging with 1 mm collimation is superior to HRCT for revealing the presence and extent of bronchiectasis [13]. Potential advantages of helical CT include detection of subtle bronchiectasis missed between HRCT sections, reduced motion artifact, and seamless reconstruction of oblique airways [8]. We have found that use of helical images when viewed in a cine format on the computer workstation are extremely useful for the detection of even subtle bronchiectaisis. A drawback of helical CT is that there is a significantly increased radiation dose to the patient compared to HRCT [8,13].

REFERENCES:

(1) J Thorac Imag 1995, 10: p.255-267

(4) Radiology 1996; 200: 673-679

(5) Radiology 1993; 188: 829-833

(6) J Thorac Imag 1995; 10(4): 236-254

(8) Radiol Clin North Am 1998; Hansell DM. Bronchiectasis. 36 (1): 107-128

(9) Radiology 1998; Song JW, et al. Hypertrophied bronchial artery at thin-section CT in patients with bronchiectasis: Correlation with CT angiographic findings. 208: 187-191

(10) Radiographics 1998; Meyer CA, White CS. Cartilagenous disorders of the chest. 18: 1109-1123

(11) AJR 1999; Cartier Y, et al. Bronchiectasis: Accuracy of high-resolution CT in the differentiation of specific disease. 173: 47-52

(12) Radiology 2003; Boehm T, et al. Thin-section CT of the lung: does electrocardiographic triggering influence diagnosis? 229: 483-491

(13) AJR 2006; Dodd JD, et al. Conventional high-resolution CT

versus helical high-resolution MDCT in the detection of

bronchiectasis. 187: 414-420

(14) Radiographics 2015; Milliron B, et al. Bronchiectasis:

mechanisms and imaging clues of associated common and uncommon

diseases. 35: 1011-1030