Extrinsic Allergic Alveolitis/ Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis:

View cases of extrinsic allergic alveolitis

Clinical:

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) comprises a group of diseases characterized by an inappropriate host response to inhaled organic or chemical allergens (smaller than 5 μm) that is often occupationally related. Although symptoms occasionally develop after just a few weeks of contact with the allergen, most cases occur following months or years of continuous or intermittent inhalation of the inciting agent [15]. A combination of immune complex disease (type III reaction) and type I (immediate hypersensitivity) and type IV (cellular mediated reaction) reaction occur as a result of exposure. Two of the most common forms of the disorder are farmers lung (due to thermophilic [heat-loving] actinomycetes in moldy hay) and bird fanciers or pigeon breeders lung (from avian protein in droppings and feathers). There are innumerable other causes of hypersensitivity pneumonitis including mushroom workers lung, bagassosis (from Thermoactinomyces sacchari in moldy sugar cane), byssinosis (cotton worker's lung), and humidifier or air conditioner lung (from T. vulgaris). Elevated antibodiy titers to inhaled antigens such as avian proteins can suggest the diagnosis. However, titers may be elevated in patients without clinical disease, and can be normal in patients with symptoms [7]. In as many as 40% of histologically proven cases of HP, the offending agent is not identified [12]. Improvement in clinical symptoms following removal of the offending antigen also supports the diagnosis [7]. Lung biopsy is often required for a definitive diagnosis [7]. Most affected patients 80-95% are non-smokers [15]. Cigarette smokers are considerably LESS LIKELY to develop HP- possibly due to increased mucociliary clearance.

Bronchoalveolar lavage characteristically reveals a lymphocyte content of more than 30% (normal less than 10%), often with an increased CD4-to-CD8 ratio of less than 1.0 (for smokers, a BAL lymphocyte count of more than 20% is used) [15].

There are essentially three phases to hypersensitivity pneumonitis- acute, subacute, and chronic [12].

The acute phase occurs after heavy exposure to antigens in a previously sensitized patient often in an enclosed space with poor ventilation [12,15]. Patients present with fever, chills, myalgia, dyspnea, leukocytosis, and other respiratory symptoms usually 4 to 12 hours following exposure (symptoms typically peak 12-24 hours after exposure [15]). Patients may present with a clinical picture resembling pulmonary edema. The symptoms usually resolve within hours to days, but may recur on re-exposure.

Subacute disease develops over weeks to months of intermittent or continuous exposure to low doses of antigen [12] and can lead to chronic or end-stage lung disease. Patients with subacute often present with the insidious onset of dyspnea and lack systemic symptoms.

Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) results from very low level persistent or recurrent exposure to antigen and is differentiated from subacute disease by the presence of fibrosis [12]. A classic temporal relationship to exposure may not be present at these stages. Between 25-40% of patients with chronic HP have evidence of lung fibrosis [13]. In patients with chronic HP and fibrosis, survival time is 3.9 to 7.1 years [13].

HP is usually best treated by removing the offending agent from the affected patients environment [15]. A course of steroids 40-60 mg of prednisone daily for a few days to weeks may improve symptoms [15]. Following treatment, patients with acute HP demonstrate complete clearing of radiographic findings. Subacute or chronic HP may not reverse.

Histologic findings in acute HP include a cellular brochiolitis with neutrophilic infiltration of the respiratory bronchioles and alveoli [12]. Subacute HP is characterized by a combination cellular bronchiolitis, loosely formed noncaseating granulomas, and lymphcytic infiltrates centered on the bronchioles [12], however, sometimes the findings may be indistinguishable from DIP or cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (BOOP). Chronic HP appears as NSIP or UIP [12].

X-ray:

CXR: On plain film, acute hypersensitivity reactions typically produce a diffuse ground glass opacity or a fine micronodular pattern. More severe cases will produce a pulmonary edema appearance [12]. The CXR is often normal in patients with mild symptoms [7]. About half of the patients with normal CXR's will have CT evidence of hypersensitivity pneumonitis [7]. Other findings include patchy or diffuse ground-glass opacity, or more rarely consolidation [15]. In the chronic stages, fibrosis predominates and manifests as volume loss, reticular opacity, and honeycombing. Gallium exam may show increased pulmonary accumulation of the radiotracer prior to x-ray changes.

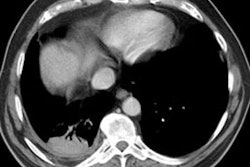

HRCT: About 8% of patients with proven HP will have normal HRCT findings [12] (although I others state that up to 50% of scans can be normal). The HRCT findings in HP are related to the stage of disease. With very heavy acute exposure to the offending antigen, a diffuse air-space consolidation resembling pulmonary edema can be seen which will resolve over a few days. The sub-acute phase occurs from several days to months after exposure. The most typical finding in sub-acute HP is scattered, poorly defined, centrilobular 1-5mm nodules distributed diffusely throughout the lungs, but primarily involving the middle and lower lung zones. The ill-defined nodules can be found at all stages of the disorder. Associated areas of ground glass opacity are also commonly seen and often produce a mosaic pattern of attenuation (up to 86% of cases). Areas of ground glass attenuation correlate pathologically with mononuclear cell infiltration of the alveolar walls [3]. Less commonly, there is widespread ground glass attenuation which is indistinguishable from desquamative interstitial pneumonitis (DIP). The areas of ground glass attenuation are usually diffuse and symmetric [12], but they may spare the periphery. In some patients the ground glass infiltrates can be patchy and asymmetric [12]. About 20% of patients demonstrate perivascular interstitial thickening which is often irregular.

A mixed appearance or "headcheese sign" can also be seen in patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis and appears as a combination of lobular areas of increased or ground glass attenuation, normal lung, areas of consolidation, and other areas of reduced lung attenuation [6,7,8,11]. The areas of decreased attenuation are secondary to chronic inflammatory infiltrates along small airways (cellular bronchiolitis) that produce bronchiolar narrowing and result in air trapping (this becomes even more apparent on expiratory imaging) [8]. Air trapping can be found in up to 90% of patients with HP, but the findings are usually limited in extent [12].

Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis develops as a result of continuous or intermittent antigenic exposure over several months or years and commonly demonstrates intralobular interstitial thickening (evidence of fibrosis) with traction bronchiectasis/bronchiolectasis predominantly involving the mid- and upper lung zones [7]. There is usually relative sparing of the lung apices, costophrenic sulci, and lung bases which aids in distinguishing this disorder from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and NSIP [2,4,10,12,14]. Other finds that aid in suggesting the diagnosis of chronic HP include the presence of lobular areas with decreased attenuation and vascularity (presumed to be secondary to air trapping) and centrilobular nodules [14]. Areas of ground glass attenuation are common, but can also be seen in IPF and NSIP [14]. Honeycombing is found in about 75% of patients with end-stage lung disease as a result of HP.

The presence of ill-defined centrilobular micronodules is a finding which can be used to help distinguish HP from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), whereas honeycombing and a lower lung zone or peripheral involvement favor IPF. Micronodules may also be identified in respiratory bronchiolitis, but many of these patients have a smoking history which is generally not associated with HP (5). Nodules associated with sarcoidosis are usually larger, better defined, and more dense than those seen in HP. Although patients with BOOP may have a similar clinical presentation to HP, the areas of parenchymal opacification are typically denser and more patchy than that associated with HP. Fine reticulations may be superimposed upon the ground-glass opacities in patients with HP and mimic NSIP [12].

Farmer's Lung:

Clinical:

Farmer's lung is the result of a type III hypersensitivity reaction to spores contained within moldy hay (thermophylic actinomyetes and microsporia faeni). Thermophilic actinomyetes are gram positive filamentous bacilli that flourish in warm (50-60? C) and moist conditions like those produced in decaying vegetation [15]. Symptoms of shortness of breath, fever, malaise, and nonproductive cough begin 4-6 hours following exposure and are generally related to the amount of exposure. A subacute or chronic form of the disorder occurs with weeks to months of continued exposure. Bronchiolitis obliterrans is seen in up to 50% of cases.

X-ray:

On plain film, CXR's are normal in up to 70% of cases, but when abnormal, acutely the disorder is characterized by a pattern of diffuse air space disease or a ground glass pattern mimicking pulmonary edema. These changes are reversible and improve over several days. Over time progresses to a granulomatous reaction that may eventually lead to a small nodular pattern, followed by interstitial fibrosis and end-stage honeycomb lung. Pleural effusion is rare and the disorder is not associated with hilar adenopathy. On HRCT ground glass opacifications with superimposed, ill-defined, centrilobular nodules can be seen during the acute or subacute period. These findings predominantly involve the midlung zones. Chronic disease produces a pattern of interstitial fibrosis. Emphysematous changes can also be seen in patients with chronic farmer's lung- even in non-smokers [12].

REFERENCES:

(1) Radiol Clin North Am 1994. High-resolution computed tomography in acute diffuse lung disease in the immunocompromised patient. Jul 32(4):731-744

(2) Radiographics 2001; Kim KI, et al. Imaging of occupational lung disease. 21: 1371-1391

(3) AJR 1997. Ground-glass opacity at CT: the ABCs. 169(2), 355-367 (No abstract available)

(4) Applied Radiol, Oct 95, p.47

(5) AJR 1995 Oct;165(4):807-811

(6) Society of Thoracic Radiology Course Syllabus 1999; Webb WR. Inhomogeneous opacity on high resolution lung CT: Differential diagnosis. p. 239-250

(7) AJR 2000; Matar LD, et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. 174: 1061-1066

(8) AJR 2000; Arakawa H, et al. Expiratory high-resolution CT: Diagnostic value in diffuse lung disease. 175: 1537-1543

(9) AJR 2005; Miller WT, Shah RM. Isolated diffuse ground-glass opacity in thoracic CT: causes and clinical presentations. 184: 613-622

(10) Radiology 2005; Lynch DA, et al. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: CT features. 236: 10-21

(11) Radiology 2006; Webb WR. Thin-section CT of the secondary pulmonary lobule: anatomy and the image- the 2004 Fleischer lecture. 239: 322-338

(12) AJR 2007; Silva CIS, et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: spectrum of high-resolution CT and pathologic findings. 188: 334-344

(13) Radiology 2007; Sahin H, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: CT features- comparison with pathologic evidence of fibrosis and survival. 244: 591-598

(14) Radiology 2008; Silva CIS, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: differentiation from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia by using thin-section CT. 246: 288-297

(15) Radiographics 2009; Hirschmann JV, et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a historical, and radiologic review. 29: 1921-1938