Fat Embolism:

Clinical:

Fat embolism (the presence of fat globules within the lung

parenchyma) occurs when fat

from a fracture of a marrow containing bone embolizes to the lungs

and other organs.

It may occur in the setting of long bone fracture, blunt trauma,

intramedullary nail fixation, percutaneous vertebroplasty, acute

pancreatitis, burns, and liposuction [5]. Respiratory symptoms are

thought to result from the metabolism of the neutral fat

particles by lipase within the lungs. The resulting free fatty

acids and glycerol are

toxic to the lung parenchyma and cause a severe inflammatory

reaction that results in

endothelial injury and increased capillary permeability [2]. This

injury is compounded by

the accumulation of inflammatory cells, particularly neutrophils,

that cause further

damage to the vasculature [3]. There may be an interval of 12-48

hours between the initial trauma and the clinicoradiologic

findings [5].

Fat embolism is common and can be detected in greater than 90% of patients with long bone fractures [1]. Fat embolism also occurs in over 90% of patients with bone fractures during orthopedic prosthesis procedures [4]. Fat embolism syndrome (FES) is a serious manifestation of fat embolism. The incidence of fat embolism syndrome is 0.5 to 3.5% in patients with long bone fracture, but can be as high as 5 to 10% in patients with multiple long bone or associated pelvic fracture [1,2,4]. It is important to remember that FES is a diagnosis of exclusion. The syndrome appears as a compbination of pulmonary, cerebral, and cutaneous symptoms including: 1) Respiratory insufficiency (acute hypoxia); 2) Encephalopathy- in up to 85% of patients consisting of confusion, restlessness, stupor, and coma; 3) Thrombocytopenia; and 4) A petechial skin rash- most commonly on the anterior thorax, anterior axillary folds, head, and neck, although the skin rash is present in only 20% to 50% of patients [2,3]. [Click here for Gurd's diagnostic criteria for fat embolism syndrome].

Urinary lipids can be positive in over 50% of cases, but the finding is not specific for FES as urinary lipids can be seen in trauma patients without FES [1]. The ture incidence is hard to determine as the syndrome is likely often masked by other physiologic derangements in severely injured patients [1]. Early fracture fixation does not increase the risk for FES [1]. Most patients begin to manifest symptoms 24 to 72 hours after injury and can have a broad range of severity. Patients that manifest symptoms within 12 hours of injury often have a more fulminant course with a higher mortality [1]. Treatment for FES syndrome is supportive [1]. Reported mortality (5% to 10%) is affected by the degree of associated injuries.

X-ray:

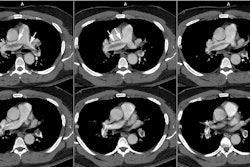

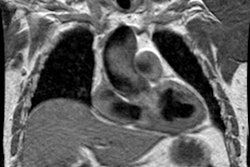

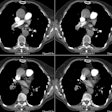

Radiographically fat embolism can appear similar to pulmonary edema/ARDS with bilateral homogeneous and heterogeneous opacities. Differentiation from cardiogenic pulmonary edema can be made based upon a normal heart size, the lack of vascular redistribution, and pleural effusions are uncommon. Mild cases may not be radiographically evident [4].

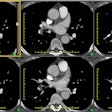

On HRCT, in mild cases of fat embolism common findings include bilateral ground-glass opacities and interlobular septal thickening [4]. Ill-defined centrilobular nodules can also be seen [4].

Ventilation perfusion scinitgraphy is normal in the majority of cases (due to the emboli's small size), but classically there is a heterogeneous perfusion pattern observed with multiple small to moderate perfusion defects scattered throughout both lungs. Segmental perfusion defects are rarely present. The V/Q scan can therefore be useful in excluding pulmonary embolism as the cause of the patients hypoxia [1].

REFERENCES:

(1) Arch Surg 1997; Bulger EM, et al. Fat

embolism syndrome. 132:

435-439

(2) J Thorac Imag 2000; Heyneman LE, Muller NL. Pulmonary nodules in early fat embolism syndrome: A case report. 15: 71-74

(3) AJR 2000; Rossi SE, et al. Nonthrombotic pulmonary emboli. 174: 1499-1508

(4) Chest 2003; Malagari K, et al. High-resolution CT findings in

mild

pulmonary fat embolism. 123: 1196-1201

(5) AJR 2017; Unal E, et al. Nonthrombotic pulmonary artery

embolism: imaging findings and review of the literature. 208:

505-516