Low doses of ionizing radiation induced molecular changes in the brains of mice that resemble the pathologies of Alzheimer's disease, according to research published online in the journal Oncotarget.

In a study from several European countries and Japan, researchers induced molecular alterations in the hippocampus of mice, which were exposed to low-dose-rate ionizing radiation treatments over 300 days. They found that the radiation changed proteins in the brain similar to a process that occurs in patients with Alzheimer's disease (Oncotarget, September 30, 2016).

"This study is the first of its kind to elucidate the protein modification alterations in [the] hippocampus when exposed to chronic low-dose-rate ionizing radiation," wrote the group led by Stefan Kempf, PhD, from the University of Southern Denmark. "Although it cannot distinguish between the effects of dose and dose rate, the comparison with previous high-dose-rate studies indicates that both play a role in the observed alterations."

Increasing radiation exposure

People of all ages are increasingly exposed to ionizing radiation from various sources, the authors noted. Not only has the use of medical diagnostics and therapeutic radiology increased rapidly, with 62 million CT scans performed each year in the U.S., but many people receive chronic occupational exposure from nuclear technologies or airline travel.

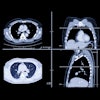

In addition, about one-third of all diagnostic CT exams are performed in the head region. Recent data suggest that even relatively low doses equivalent to just a few CT scans could trigger molecular changes associated with cognitive dysfunction resembling what is seen in normal aging and Alzheimer's disease, the group wrote.

Previously, a total body dose of 0.5 Gy administered to neonatal mice was shown to result in long-term cognitive dysfunction and enhanced levels in the adult brain of total tau protein, a marker of Alzheimer's disease pathology, according to the authors. Similarly, total body irradiation of an 8-week-old mouse induced early transcriptional response of several Alzheimer's disease-related genes in the hippocampus, but without memory impairment.

Effects of chronic exposure?

The current study looked at the effect on the hippocampus of chronic low-dose-rate radiation exposure of 1 mGy per day or 20 mGy per day over 300 days with cumulative doses of 0.3 Gy and 6.0 Gy, respectively. An apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-deficient mutant C57Bl/6 mouse served as an Alzheimer's model.

Mass spectrometry of the exposed mice detected a marked alteration in the phosphoproteome at both dose rates. The radiation-induced changes were associated with control of synaptic plasticity, calcium-dependent signaling, and brain metabolism, the authors wrote.

In addition, inhibition of CREB cellular transcription factor signaling was found at both dose rates, while Rac1-Cofilin signaling was activated only at the lower dose rate. Similarly, a reduction in the number of activated microglia in the molecular layer of hippocampus that paralleled reduced levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression and lipid peroxidation was significant only at the lower dose rate.

Both dose rates in the study are capable of inducing molecular features that are reminiscent of those found in Alzheimer's disease neuropathology, Kempf and colleagues concluded.

They exposed mice to a cumulative dose of radiation that was more than 1,000 times smaller than what a patient gets from a single CT scan in the same time interval, Kempf said in a statement accompanying release of the study. Even then, the group could see changes in the synapses within the hippocampus that resemble Alzheimer's pathology.

"All these kinds of exposures are low-dose, and as long as we talk about one or a few exposures in a lifetime I do not see cause for concern," Kempf said. "What concerns me is that modern people may be exposed several times in their lifetime and that we don't know enough about the consequences of accumulated doses."