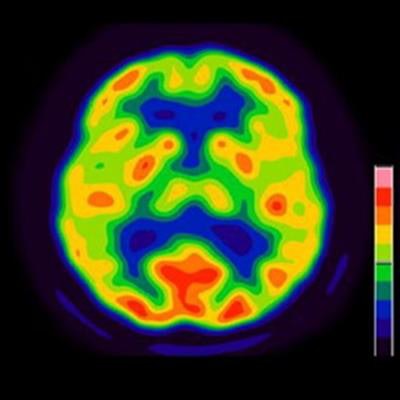

Patients on ketogenic diets appear to have circulating metabolites that reduce the uptake of F-18 FDG radiotracer in brain PET imaging, according to an Australian group of researchers.

Nuclear medicine physicians from the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital studied images of patients who followed a strict keto diet and then underwent PET scans. They found increased serum ketone levels suppressed brain F-18 FDG uptake in patients and suggested these levels need to be accounted for when scans are compared with those of the patients not on the diet.

"This regional difference should be taken into consideration when selecting the appropriate brain region for SUV [standard uptake values] normalization, particularly when undertaking database comparison in the assessment of dementia," wrote lead author Dr. Olivia Bennet and colleagues in an article published December 15 in the European Journal of Hybrid Imaging.

F-18 FDG-PET imaging is widely used in cardiovascular inflammatory disorders and cancer to identify increases in metabolic glucose activity, which partly drives disease activity. Patients referred for PET imaging may be asked to follow a ketogenic diet prior to the scan, as it reduces blood glucose and allows for more accurate evaluations.

Because of the range of proven and postulated benefits of ketosis, however, more patients are attending F-18 FDG-PET scans of the brain while on the keto diet, and the relationship between F-18 FDG brain tissue uptake in these patients and their blood glucose and ketone levels are poorly understood.

To close the knowledge gap, Bennet's team analyzed brain images from 52 patients who underwent whole-body F-18 FDG-PET/CT scans (from the skull vertex to the thighs) for possible cardiac sarcoidosis or suspected intracardiac infection following a two-day ketogenic diet and prolonged fasting. SUV based on body weight (SUVbw) for whole brain and separate brain regions were compared with serum glucose and serum ketone body levels.

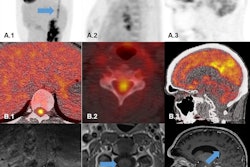

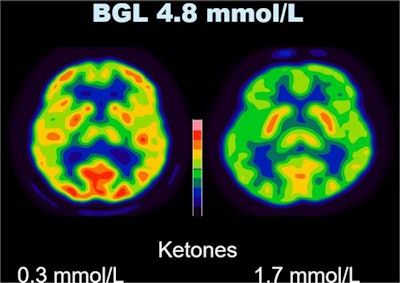

Effect of serum ketone level on cerebral SUVbw. Sample images of two patients thresholded identically with the same blood glucose level, but different serum ketone levels illustrate the reduction in FDG uptake in the brain seen with a higher serum ketone level. Image courtesy of the European Journal of Hybrid Imaging through CC BY 4.0 International License.

Effect of serum ketone level on cerebral SUVbw. Sample images of two patients thresholded identically with the same blood glucose level, but different serum ketone levels illustrate the reduction in FDG uptake in the brain seen with a higher serum ketone level. Image courtesy of the European Journal of Hybrid Imaging through CC BY 4.0 International License.As they expected, the researchers found a negative association between serum glucose levels and whole-brain F-18 FDG uptake. However, they also noted a reduction in SUVbw due to increasing serum ketones levels that were independent of and in addition to the effects of glucose.

"Suppression of F-18 FDG brain uptake during ketosis has been observed previously in humans using PET scans under experimental conditions, but to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time it has been found to have a measurable effect on F-18 FDG-PET scans performed for clinical purposes," the authors wrote.

Moreover, the magnitude of the reduction in SUVbw related to serum glucose level and serum ketone level was found to be greater in the precuneus area of the brain (which is responsible for recollection and memory) than in the cerebellum or whole brain, they added.

"Based on our findings, we suggest that when SUV cutoffs are used to determine whether patterns of F-18 FDG uptake fall within the physiologic or pathologic range, [blood glucose level] and serum ketone levels should both be considered," Bennet's team concluded.