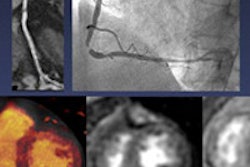

BOSTON - Nuclear medicine technologists were nearly as accurate as cardiologists in reading stress-first SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) studies, according to research presented at the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) meeting. The study hints at a role for technologists in determining which patients could avoid the rest portion of the scans.

Of 60 patients in the study, nuclear medicine technologists correctly identified whether 53 (88%) needed additional rest imaging, coming close to the performance of cardiologists, who correctly identified 58 (97%) individuals. Furthermore, the technologists achieved this result with no formal training in interpreting the images.

The researchers are expanding their study, but they believe the findings indicate that technologists could help triage which patients should be sent on for rest SPECT MPI, reducing healthcare costs and lowering radiation exposure.

Cost-saving protocol

Current guidelines recommend that two SPECT MPI scans -- typically rest first and stress second -- be performed before confirming that the exam is normal. However, the nuclear medicine community is looking for alternative protocols to improve workflow and reduce the radiation dose from the two scans.

One such alternative is by performing a stress MPI test first. This could allow imaging facilities to avoid unnecessarily exposing patients to additional radiation with a second isotope injection, while at the same time saving on exam costs, according to lead author Dr. Waseem Chaudhry, a nuclear cardiology fellow at Hartford Hospital in Hartford, CT.

But this diagnostic pathway is not without its disadvantages.

"One limitation of the protocol is the requirement for a physician to read the stress-first images upon completion to determine the need for the rest portion of the study," the researchers noted. "This hurdle to performing stress-first studies could be eliminated if the nuclear technologist can make this determination."

The prospective study included 29 men and 31 women from Hartford Hospital and Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City who had an average age of 60 years (± 12 years). The patients underwent attenuation-corrected stress-first SPECT MPI with technetium-99m (Tc-99m) over a one-month period.

Four cardiologists and six nuclear medicine technologists with varying degrees of experience (14.9 ± 6.4 years) were asked to interpret the SPECT images using a standard 17-segment scoring model to determine the need for rest images. Both of these groups were blinded to the patients' clinical and stress test data. Their results were compared with the conclusions of a physician who did have access to the patients' clinical and stress test results (serving as the gold standard).

The technologists correctly determined whether 88.3% (53) of the 60 patients needed a rest test. For two studies, unnecessary rest images were requested, and for five studies, rest images deemed necessary were not requested. Meanwhile, the cardiologists correctly identified 96.7% (58) of the patients requiring rest images; for two studies, rest images were requested for studies eventually deemed normal.

Interestingly, the least-experienced technologist -- just two years out of school -- achieved a perfect score.

"He did eight studies, and his rate of correctly identifying the stress-first study and acquiring or not acquiring the rest part was 100%," Chaudhry said.

Based on the preliminary results, Chaudhry and colleagues concluded that having technologists screen stress-first SPECT MPI scans could improve workflow in nuclear cardiology practices and laboratories and significantly reduce radiation exposure, helping to achieve dose reduction goals.

Expanding the study

The researchers are continuing to expand their prospective study at both institutions. Currently, there are approximately 300 patients in the study; their goal is to increase participation to 500 patients and also to add a third imaging site.

The promising early results have not yet prompted Hartford Hospital or Mount Sinai to change their policies regarding technologists' role in stress-first SPECT MPI studies.

"We want to get as many patients and technologists involved as possible in the study" before making any changes, Chaudhry said. "Even if the percentage of correct answers from the technologists drops with more of them included in the study, we can provide education to technologists to improve the results."

To the best of his knowledge, this is the first study to compare technologists' reading abilities against cardiologists without any additional education or training for the technologists, he said.

"Keep in mind, this study was done without any formal education [for the technologists] on how to read the studies," he said. "This was baseline knowledge to see what they can do. I am sure if we train them even more, we will see that number improve."