Could menopausal status be a factor in why women are more frequently afflicted with Alzheimer's disease than men? Using PET scans, researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine and the University of Arizona Health Sciences may have found a connection. Results of their study were published online October 10 in PLOS One.

The findings could lead to more efficient screening tests and early intervention to reverse or slow metabolic changes that cause the progression of Alzheimer's disease.

"This study suggests there may be a critical window of opportunity, when women are in their 40s and 50s, to detect metabolic signs of higher Alzheimer's risk and apply strategies to reduce that risk," said lead author Dr. Lisa Mosconi, an associate professor of neuroscience in neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine.

For the study, Mosconi and colleagues used PET to measure glucose in the brains of 43 healthy women between the ages of 40 and 60. Of those subjects, 15 women were premenopausal, 14 were transitioning to menopause (perimenopause), and 14 were menopausal.

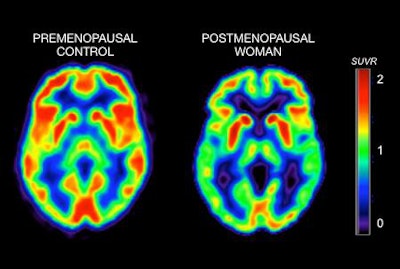

PET images show brain activity in a premenopausal woman (left) and in a postmenopausal woman (right). Brighter colors indicate higher metabolism, while darker colors indicate lower metabolism. The postmenopausal scan appears greener and darker, which means the woman's brain has substantially lower activity (more than 30% less) than the one to the left (no signs of menopause). Images courtesy of Weill Cornell Medicine.

PET images show brain activity in a premenopausal woman (left) and in a postmenopausal woman (right). Brighter colors indicate higher metabolism, while darker colors indicate lower metabolism. The postmenopausal scan appears greener and darker, which means the woman's brain has substantially lower activity (more than 30% less) than the one to the left (no signs of menopause). Images courtesy of Weill Cornell Medicine.Women who had undergone menopause or were perimenopausal had markedly lower levels of glucose metabolism in several key brain regions than women who had not yet experienced menopause, the researchers found.

The menopausal and perimenopausal subjects also showed reduced levels of brain activity for a metabolic enzyme called mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase. These women also had lower scores on standard memory tests.

"Our findings show that the loss of estrogen in menopause doesn't just diminish fertility," Mosconi said in a press release. "It also means the loss of a key neuroprotective element in the female brain and a higher vulnerability to brain aging and Alzheimer's disease."

The researchers plan to expand their patient group and conduct a longer-term analysis of neural and metabolic markers during and after menopause. One goal is to develop biomarkers that could help identify people who are at greater risk for Alzheimer's.