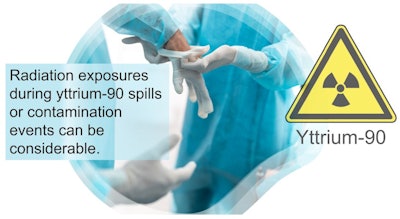

Contamination during yttrium-90 (Y-90) radioembolization procedures can lead to significant radiation exposure for medical personnel, according to a study published August 16 in the Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology.

A team led by Michael Arseneault, MD, of Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, calculated radiation exposure levels from Y-90 contamination events during radioembolization procedures. Based on the results, they urged medical personnel to be prepared to respond quickly when a spill occurs.

"Annual skin dose limits can be surpassed within seconds from contamination by a tiny droplet," the group wrote.

During radioembolization, interventional radiologists and nuclear medicine personnel inject vials of tiny Y-90 radioactive beads into arteries that supply liver tumors. These microspheres kill cancer cells while sparing surrounding tissue. Aspects of the delivery process during the hours-long procedures are susceptible to operator error and can result in a spill or contamination, with spills threatening staff safety, the researchers explained.

In this study, the group used computer simulations to calculate radiation doses from various contamination scenarios.

In one simulation, for instance, the researchers considered a potential worst-case scenario in which a droplet originated from a 20-milliliter syringe containing 18 gigabecquerel (GBq) of radioactivity. With direct skin contamination, the operator's yearly recommended occupation exposure limit of 500 millisieverts (mSv) was reached within 23 seconds, the group reported.

A graphical abstract. Image courtesy of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology.

A graphical abstract. Image courtesy of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology.The group then simulated the radiation exposure level assuming that staff members were wearing a gown and surgical gloves, as recommended. The team found that the gown and gloves provided some protection by attenuating the radiation, but even with this precaution, the dose remained considerable, they found.

"The yearly limit of 500 mSv is surpassed within 1 min even with gown and surgical gloves (cover protection)," they wrote.

Moreover, less than two minutes of direct skin contact by a single droplet and less than three minutes of contamination over the 0.4-millimeter gloves and 0.5-millimeter gown were required to reach the 2,000-mSv threshold at which cutaneous radiation injury can occur, the researchers added.

"Personal protective equipment such as surgical gloves and gowns must not be relied on as a means of shielding since they provide only partial attenuation of the radiation from direct contamination," the group wrote.

To that end, the researchers recommended that operators wear two layers of surgical gloves. According to their calculations, this offers the best ratio of radiation protection without compromising dexterity, and they noted this recommendation aligns with that of the International Commission on Radiological Protection.

Wearing double gloves during selective internal radiation therapy procedures allows individuals to quickly remove a contaminated outer glove with a gloved hand, the group wrote.

"Every team member involved in Y-90 radioembolization should be well versed in handling a spill or contamination," the researchers concluded. "Instructions for emergency procedures should be made available in every spill kit if there is any doubt about how to proceed. [Interventional radiology] suites should have emergency equipment readily available for handling spills."

A link to the abstract and full study can be found here.