A new review of the literature on gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) for MRI scans has found a "significant gap in knowledge" on the health effects of gadolinium accumulation in tissue. Researchers are calling for new clinical studies, as well as the development of a drug that would remove retained gadolinium from the body.

Published online April 6 in BioMetals, the review of studies on gadolinium contrast was performed by a research team from the MedInsight Research Institute in Baltimore and the Center for Drug Repurposing at Ariel University in Israel.

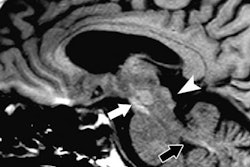

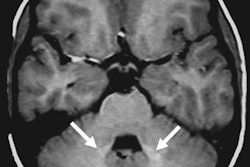

It was previously believed that GBCAs are excreted from the body intact, the researchers noted, but recent studies indicate that gadolinium can accumulate in patients, even those with normal renal function.

The clinical significance of gadolinium retention is unknown, due to a lack of retrospective or prospective clinical cohort studies on the association between recurrent exposure to GBCAs and postexposure medical conditions (apart from gadolinium's known link to nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, or NSF, in patients with renal failure).

But the potential for toxicity can be inferred from published data from in vivo and in vitro studies of gadolinium toxicity, as well as GBCA biochemistry and the stability of different types of gadolinium formulations. Some cases of acute gadolinium toxicity have already been reported, but "the potential for chronic and delayed manifestation of toxicity should be considered," they noted.

The issues with gadolinium are thought to occur when the gadolinium molecule becomes disassociated from the chelating agent, a carrier molecule that modifies how gadolinium is distributed in the body and overcomes its toxic properties while maintaining its value as a contrast agent. Certain GBCA formulations, such as macrocyclic agents, are believed to be stabler than linear GBCAs, according to the researchers.

They also examined papers exploring the possible biochemical mechanisms that might be contributing to gadolinium toxicity in conditions such as NSF. Various studies have suggested apoptosis, oxidative stress, and transmetallation as being among the processes that could result in adverse events.

Finally, the researchers made note of recent studies pointing to compounds that could protect against the effects of GBCAs, such as deferiprone, which has been shown to protect against NSF in mice, or N-acetyl-cysteine, which inhibits gadolinium-induced cell death and has also been shown to prevent GBCA-induced nephrotoxicity in rats with chronic renal failure. Offering such agents on a pretreatment basis could be a solution for patients in whom GBCA administration is the best option, they wrote.

In a press release that accompanied the study, the researchers called for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to take stronger action on the issue of gadolinium retention. They acknowledge that the FDA began a review of the tissue-accumulation issue in July 2015, but the agency at the time claimed there was no information on the health risks of gadolinium, a position that "is no longer tenable" given the findings of the literature review, according to lead author Moshe Rogosnitzky of Ariel University.

Rogosnitzky called for the scientific community to develop treatments for what he called "gadolinium overload," noting that the literature review could not find "a single suitable drug to swiftly remove gadolinium from the body." He believes that a good first step would be to study existing chelator drugs currently being employed for other metal toxicities, and assess their potential for reducing gadolinium accumulation.

"With the ominous discovery that gadolinium is retained in healthy patients, there is a critical shortage of scientific information regarding how to assess gadolinium toxicity, and perhaps most importantly, how to treat it," Rogosnitzky said.