FDG-PET can diagnose suspicious mammographic findings better than all of the anatomical imaging modalities put together. And because PET reduces the number and frequency of exams required to rule out breast cancer, it can ease women's fears about the disease.

Dr. Johannes Czernin, director of nuclear medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, made the remarks Friday during a teleconference sponsored by the Los Angeles-based Academy of Molecular Imaging. Several prominent nuclear medicine researchers discussed PET's role in diagnosing cancer during the organization's annual meeting last week in Orlando, FL.

Czernin said that FDG-PET imaging is making important inroads in breast cancer detection, staging, and restaging after treatment, as well as in monitoring breast cancer following treatment. By far the most important indication for PET is in women with dense breasts, Czernin said.

"Dense breasts occur more frequently in younger women, and women [undergoing] estrogen replacement treatment," he said. Moreover, alternative screening methods are sorely needed, because 30% to 40% of women have dense breasts, yet mammography misses about 50% of cancers in these women, he said.

Compounding the problem is that dense breasts themselves carry a higher risk of breast cancer. Women with dense breasts are approximately five times as likely to develop breast cancer as women without dense breasts, he said, for reasons that are poorly understood.

"It's probably that dense breast tissue has a higher propensity for developing DNA abnormalities because of higher cell replication rates," Czernin said. "So based on the fact that there are a lot of women who are not well-served by mammography, we believe that mammography needs help."

The problem is that the two most obvious choices as mammography adjuncts -- MRI and ultrasound -- haven't really improved detection rates, he said. At the same time, breast cancer has been shown to be glucose-avid, and PET has been shown to be about 80%-85% accurate in detecting breast cancer.

Czernin said more PET studies in breast cancer detection are needed, but the numbers of patients needed to look at PET in a screening population would be so large as to make the cost prohibitive, he said. Therefore, the best research approach would be to begin with women who have dense breasts, in addition to a genetic predisposition, family history, or other factors that put them at high risk of developing the disease. Fortunately, he said, the cost of FDG can be expected to drop as its use becomes more widespread in medical practice.

Recurrent cancer and treatment monitoring

PET can also be very useful in detecting or ruling out recurrent cancer, he said.

"Patients with breast cancer remain anxious. For the rest of their lives, they are worried about recurrence," he said.

Czernin's group studied a group of patients who had been treated for breast cancer, and found that these patients underwent an average of 3.5 tests per patient within the three months preceding the PET exam.

"We then performed the PET study and we found out we can predict with high accuracy whether these patients will have disease recurrence or will remain disease-free," Czernin said. "We found we can do that better [with PET] than with the combination of all conventional imaging techniques that we applied."

Finally, PET is extremely useful in monitoring the effects of chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Chemotherapy does not have a high success rate in treating breast cancer, he said, so finding out sooner rather than later when chemotherapy isn't working can avoid serious side effects related to the treatment.

Developing dedicated breast scanners

Dedicated breast PET scanners currently being developed might be very useful for screening, he said. And while it's important to look at the lymph node status as a second step, screening only the breasts with FDG would be a sufficient first step for screening a high-risk screening population.

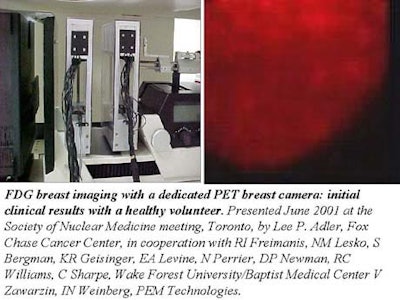

Several researchers have been working on designing and testing dedicated FDG breast cancer imaging devices. Among the pioneers in the field are Dr. Chris Thompson from the Montreal Neurological Institute and Joel Karp from the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Dr. Lee Adler from the Fox Chase Cancer Center, also in Philadelphia, presented images acquired with his dedicated scanner at this year's Society of Nuclear Medicine meeting in Toronto.

|

Another of the breast PET scanning pioneers, Simon Cherry from the University of California, Davis, spoke with AuntMinnie.com about his team's efforts to develop a working multiplanar breast imaging device by mid-2002.

"Some of the people have been building conventional PET detectors in traditional mammographic gantries or in biopsy gantries," he said. "What they want to do is coregister the planar x-ray mammograph with a planar image using FDG, and use those images together."

The problem with that approach is that mammography is inherently a high-throughput process, and breast PET will always be too slow, Cherry said. PET, even dedicated breast PET, should be kept separate, and used to examine suspicious mammography findings in a much smaller number of patients. Moreover, the imaging method will be crucial to the results, he said.

"We want to do tomography, not just projection imaging," Cherry said. "So we want to get a number of views around the breast and actually reconstruct cross-sectional images, whereas what a lot of other people are doing is getting single-projection images, just like a mammogram."

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

October 29, 2001

U.S. approves PET for re-staging breast cancer, June 20, 2001

Medicare coverage of PET imaging for breast cancer to be challenged, June 8, 2001

SNM says HCFA understates PET's value in breast imaging, June 8, 2001

Start-up enters breast imaging arena with scintimammography, PET offerings, March 14, 2001

Positron emission mammography shows promise, January 5, 2001

HCFA broadens Medicare coverage for PET, December 18, 2000

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com