Most women either under- or overestimate their lifetime risk for developing breast cancer, according to a study to be presented on September 7 at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2013 Breast Cancer Symposium (BCS) in San Francisco.

Dr. Jonathan Herman, from Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine, discovered that less than 10% of almost 10,000 women surveyed accurately estimated their breast cancer risk -- a discouraging finding, since women need to have accurate knowledge about their own breast cancer risk to make appropriate decisions regarding screening and prevention.

"It's imperative that women understand their risk of breast cancer," Herman said during a press conference on September 4. "If they have good knowledge, they can work with their doctor to set up an appropriate protocol for them that could include early detection modalities or chemoprevention medications."

Herman surveyed 9,873 women, 35 to 70 years of age, who were undergoing breast cancer screening at 21 mammography centers on Long Island, NY. The survey asked women to estimate their own risk of developing cancer over the next five years and over their lifetime. It included questions about patient demographics (race/ethnicity, religious affiliation, education, marital status, household income, health insurance), breast cancer risk factors (age at the time of first menstrual period, age at the time of giving birth for the first time, personal and family history of breast cancer, breast cancer biopsy findings), and any prior breast cancer risk assessments and discussions.

Many of the questions were adapted from the U.S. National Cancer Institute's Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool, an interactive application that doctors use to estimate a woman's risk of developing invasive breast cancer.

For each survey respondent, Herman compared the calculated actual lifetime risk to the woman's subjective risk estimate. If a woman's personal estimate differed from the calculated value by more than 10%, it was categorized as inaccurate.

Among study participants, 707 women (9.4%) accurately estimated their breast cancer risk, 3,359 (44.7%) underestimated their risk, and 3,454 (45.9%) overestimated risk. When parsed by ethnicity, Caucasian women were more likely to overestimate their risk, whereas African-American, Asian, and Hispanic women were more likely to underestimate their risk. Although these differences between groups were statistically significant, the overall understanding of breast cancer risk among all subgroups in the study was low.

"It's disconcerting that only 9% of women we surveyed could accurately estimate their breast cancer risk, despite ongoing patient education efforts," Herman said. "We would have hoped that more women would have spoken to their physicians about it. Doctors need to do a better job at sitting patients down and assessing their risk."

Radiation therapy and DCIS

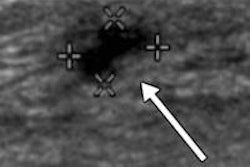

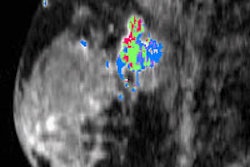

Two studies in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) were also highlighted during the ASCO press conference. One study showed that radiation therapy for DCIS does not increase cardiovascular disease risk, while a second study found that having MRI in addition to mammography -- either before or immediately after surgery -- did not reduce recurrence rates in women with DCIS.

PhD candidate Naomi Boekel, of the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam, found that women who had received radiation therapy to treat DCIS had no increased risk of cardiovascular disease compared to the general population of Dutch women. They also did not have a greater risk compared to DCIS patients treated with surgery only.

"These results may be helpful to women who are deciding on their treatment plan and seem reassuring for DCIS survivors treated with radiotherapy," Boekel said during the press conference.

Boekel and colleagues used data from 10,468 women in the Netherlands diagnosed with DCIS before the age of 75 between 1989 and 2004. Seventy-one percent of the women were treated with surgery alone and 28% were treated with surgery and radiotherapy. The median follow-up period was 10 years.

DCIS survivors had a similar risk of dying of any cause compared to the general population of Dutch women, but they actually had a 30% lower risk of dying from cardiovascular disease. Boekel attributed this finding to the possibility that the women were more health conscious than those in the general population -- prompting them to undergo breast cancer screening -- or that they assumed a healthier lifestyle after they had been diagnosed with DCIS.

Finally, researchers from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center found that adding MRI to mammography before or immediately after surgery was not associated with reduced local recurrence or contralateral breast cancer rates among women with DCIS who were treated with lumpectomy.

The findings suggest that MRI does not improve long-term outcomes for most women with DCIS, according to lead study author Dr. Melissa Pilewskie.

"We did not find association between perioperative breast MRI and decreased rates of locoregional recurrence or contralateral breast cancer development," Pilewskie said during the press conference. "And in absence of evidence that MRI improves surgical management or long-term outcomes, its routine use for DCIS should be questioned."