There's an optimal range for mammography screening recalls that maximizes the detection of life-threatening cancers and minimizes the harms of false positives and overdiagnosis, according to a presentation delivered on Wednesday at ECR 2019 in Vienna.

Finding the recall rate "sweet spot" is important, especially when the range is wide, said presenter Dr. Matthew Wallis of Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust.

"One of the major screening challenges, at least in the U.K., is that we have very tight definitions and standards for recall rates, but we're not very good at enforcing them," he said. "There's a very wide range of recall rates in the U.K., particularly for first screening mammograms -- from 3.5% to 15%. If you've got that kind of range, something must be going on that needs to be addressed."

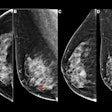

Low recall rates are associated with low cancer detection and low sensitivity. But high recall rates can also be problematic, Wallis and colleagues noted. As recall rates rise, the cancer detection rate for invasive cancers and high/intermediate-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) reaches a plateau above which almost all recalls are false positives.

The group modeled the association between cancer detection and recall rates to better understand the optimal balance of harm and benefit of screening mammography. The study included data from 11.3 million screening exams taken between April 2009 and March 2016. Of these, 2.3 million were prevalent (first) screens in women between the ages of 45 and 52, and 8.9 million were incident (further screening) exams in women between the ages of 53 and 70. The team also included previously published data from a Dutch screening program.

From their model, Wallis and colleagues found that the following recall rate ranges appear to optimize the benefit/harm ratio of mammography screening:

- Prevalent screening: 4.6% to 7%

- Incident screening: 2.6% to 4%

"If your recall rate is less than 4.6% for first screening mammograms, you're probably not finding enough cancers, but if your rate is over 7%, you're probably doing more harm than good," Wallis said.

He and his colleagues hope other European countries will model their recall rates as well so the data can be assessed in the context of other screening programs.

"For all cancers, both prevalent and incident, the more you recall, the more false positives," he concluded. "Our model predicts there is a recall range that optimizes detection of important cancers while minimizing harm of false positives and potential overdiagnosis of low-risk cancers."