Images of spry young gymnasts spinning, twisting, and flying through the air are always a highlight of the Olympic Games. Historically, women's gymnastics has drawn significant media and audience attention, whether it was to see Nadia Comaneci's bouncing ponytail or Mary Lou Retton's blinding smile. This year should prove no exception, as viewers tune in to see if Courtney Kupets can execute a perfect Podkopayeva vault or if Mohini Bhardwaj will make good on actress Pamela Anderson's $20,000 donation for her training.

But the flip side of women's gymnastics is the prevalence of acute injuries (Athens-bound Tabitha Yim had her Olympics dream dashed by an Achilles tendon tear during a June training session), as well as psychological issues such as eating disorders and body dysmorphia. This high-impact sport can also result in serious spinal damage, including disk degeneration, spinal lesions, Schmorl's nodes, and other abnormalities. A survey of 24 retired German gymnasts found a high incidence of osseous lesions, bilateral spondylolysis, unilateral spondylolysis, and scoliosis (Sportverletz Sportschaden, December 1992, Vol. 6:4, pp.156-160).

These degenerative conditions can render gymnasts susceptible to thoracolumbar fractures, which make up anywhere from 2% to 13% of spinal injuries in female gymnasts, according to an article by neurosurgeon Dr. Federico Vinas (eMedicine, January 28, 2004).

"Back bends and other activities that cause the spine to curve backward can cause fractures of the spine in young gymnasts. These fractures ... may go unnoticed for years," explained orthopedic surgeon Dr. Ellen Raney of the Honolulu Shriners Hospital in Honolulu, HI.

"However, teenagers who remain active in gymnastics may develop back pain because of these earlier fractures," Raney wrote in a Hughston Health Alert from the Hughston Sports Medicine Foundation, based in Columbus, GA. "Teenage gymnasts may need bracing or surgery to treat the fractures."

Examples include the case of an elite female gymnast who had several spontaneous fractures of the right lumbar pedicle over the course of her career, yet continued to train and compete (Spine, October 1, 2000, Vol. 25:19, pp. 2541-2543).

Imaging thoracolumbar injuries is best done with multidetector-row CT (MDCT) and some MRI, according to Dr. Georges El-Khoury, director of the musculoskeletal radiology section and professor of radiology and orthopedics at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City. However, MDCT and MRI are not competing modalities in this instance.

"Each modality has its own indications, but often we find ourselves doing both to complement each other," El-Khoury said in a presentation at the 2004 International Symposium on Multidetector-Row CT in San Francisco. El-Khoury offered a primer on both modalities for assessing the thoracic and lumbarsacral spine both before and after surgical treatment.

"MDCT is best suited for bone and hardware. MRI is ideal for soft tissues in the spine like neural elements, disk ligaments, marrow, as well as a few collections like cysts and abscesses, hematomas, and masses like neoplasm," El-Khoury said.

Indications for MDCT

The main goal of MDCT in spinal trauma is to assess the severity of injury and the degree of stability. The modality also has value for confirming the presence or absence of fractures suspected on x-ray, as well as looking for additional or occult fractures.

In either case, MDCT imaging is paired with a classification system, most commonly Denis' three-column concept. "(Denis) proposed that the middle column is pivotal for preserving or maintaining spinal stability. So if you have a spine that is fractured (and) all three columns are affected, then the spine is unstable," El-Khoury explained.

In addition, Denis' system breaks down thoracolumbar fractures into four types (Spine, November-December 1983, Vol. 8:8, pp. 817-831):

- Compression fracture

- Burst fracture

- Seat-belt fracture

- Fracture dislocation

Compression is the most common and most benign, El-Khoury stated. Burst fractures are particularly unstable, especially when they involve all three columns. Flexion-distraction injuries make up seat-belt fractures. Finally, "the worst type is the fracture dislocation, in which two-thirds of these patients have neurological symptoms, and all three columns are involved," he said.

"Every time you see a high-energy injury, you have to look for other noncontiguous fractures," El-Khoury said. MDCT is particularly helpful in multilevel and/or noncontiguous fractures, offering distinct advantages over MRI or x-ray. These fractures are difficult to see on plain film, which cannot offer information on the full extent of a spinal injury. In contrast, MRI may offer too much information.

"There's a problem with using MRI for multilevel fractures because it confuses the surgeon," El-Khoury said. "What the surgeon does is go two levels above and two levels below the fracture, puts plates and screws, and tries to stabilize it. With MRI, bone bruises are interpreted as microtrabecular fractures. If the treatment involves using hardware, then the surgeon is really in a bind. Can he put screws in an area that is bruised?"

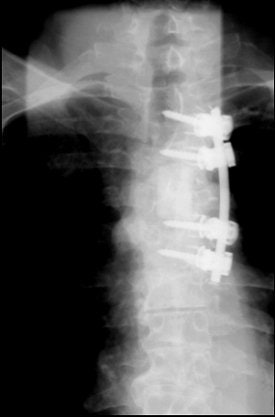

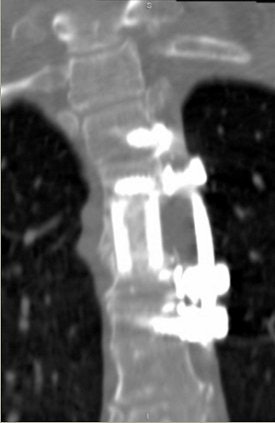

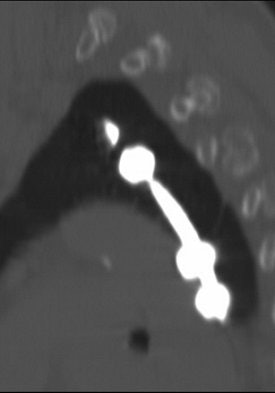

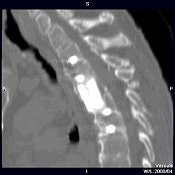

CT also can aid in finessing corpectomy procedures done to treat burst fractures. El-Khoury described an emergency case in which imaging saved the patient from further disaster (images A-F below).

"This patient arrived at the ER paraplegic. We see a little compression here, but we cannot see the entire problem. When we do CT, we see that this is a huge burst fracture. This was fairly acute. (The surgeon) did a corpectomy, which we followed with CT. He put a graft, two levels above and below the fusion," El-Khoury said. "When we looked closely at the CT, we noticed that the lower two screws are sitting and indenting the aorta. We called the surgeon and told him this: 'You have a situation in which you have metal screws pulsating against an aorta, and you know who is going to win in the end.' So the surgeon did an angiogram. The surgeon went in, removed the screws, and fused the patient from the back."

|

Image A

|

Indications for MRI

Shifting gears from fractures, MRI is best for studying patients with myelopathy caused by spinal trauma, such as disk herniation or cord abnormalities. It also has value for evaluating 1- to 2-degree epidural abscesses, as well as assessing post-traumatic epidural hematomas, El-Khoury said.

"Acute myelopathy is the most common cause of emergent MRI in the middle of the night. The (spinal) cord does not tolerate acute compression at any period of time," he noted. "Acute compression should be relieved (for) any hope of improvement. The thoracic spine is the most vulnerable segment of the spine because the canal is narrow compared to the cord, and the blood supply to the midthoracic spine is not very good."

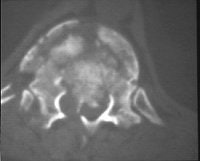

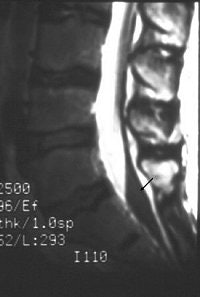

Young gymnasts are particularly susceptible to disk herniation (Neurosurgical Focus online, November 1, 2002, Vol. 13:2). Disk herniation (image G below) in the thoracic spine is more often associated with neurological deficits. Patient management changes with the presence of a disk herniation, El-Khoury said. For gymnasts, delayed or improper treatment can lead to spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis, according to the Lumbar Spine Injuries Laboratory at the University of West Alabama Athletic Training and Sports Medicine Center in Livingston, AL.

|

Image G

|

Finally, MRI can be used to study dural tears resulting from spinal fractures. Dural tears may result in entrapment of nerve roots between laminar fragments (images H-J above). Such dural tears may delay, if not preclude, recovery, El-Khoury said. MRI has been found to be 100% sensitive and 74% accurate for diagnosing dural tears as a result of burst fracture, he added.

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

August 17, 2004

All images courtesy of Dr. Georges El-Khoury.

Related Reading

Algorithm identifies osteopenic women at increased risk of fracture, May 25, 2004

Ten years along, MDCT speeds the need for PACS, May 5, 2004

Copyright © 2004 AuntMinnie.com