STOCKHOLM - As if the pressures of young adulthood weren't enough, thirtysomethings can add dementia to their list of things to worry about. A new study has detected patterns of glucose metabolism in young adults at risk of Alzheimer's disease that match those of Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients decades older.

The study was presented on Tuesday at the International Conference on Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders by Dr. Eric Reiman, director of the Arizona Alzheimer's Disease Center and Good Samaritan Regional Medical Center in Phoenix, AZ. The findings build on previous research showing that metabolic changes in brain function can be visualized by FDG-PET long before the development of structural changes associated with Alzheimer's disease.

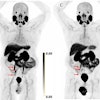

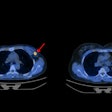

FDG-PET studies of AD patients reveal characteristic metabolic abnormalities that become more pronounced as the disease progresses. These changes include declines in glucose metabolism in the posterior cingulate, parietal, temporal, and prefrontal cortices, Reiman said.

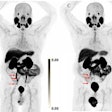

His group has been using PET to track the progression of these declines in people who are cognitively normal, yet carry the alipoprotein E4 (APO E4) allele that signals a genetic risk of developing late-onset AD.

In a previous study, the group demonstrated that middle-aged APO E4 carriers had glucose metabolism patterns that were similar to those of actual Alzheimer's patients. Reiman and colleagues wanted to see if the same changes could be seen in a younger generation of cognitively normal APO E4 carriers.

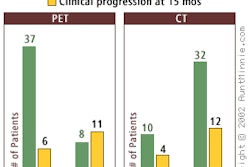

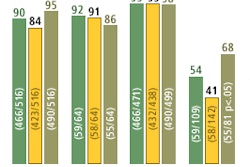

The study examined 12 APO E4 carriers and fifteen normal control subjects. The average age of all subjects was 31 ± 5 years. Subjects underwent a battery of neurological tests, psychiatric evaluations, dementia and depression tests, and MR imaging as well as FDG-PET.

An automated algorithm was used to generate 3-D T-score maps designed to show significant deviations from normal brain activity. The results were then compared with maps previously generated from patients with probable AD. Normal patients were used in both groups to control for normal variations in pontine measurements, Reiman said.

Based on neuropsychological test score results, the researchers found no significant differences between the at-risk and the control groups. However, a comparison of FDG uptake in four brain regions commonly affected by Alzheimer's disease told a different story. The group found pronounced reductions in uptake, ranging from 8% to 10.5% in the four regions, among APO E4 patients.

The changes are statistically significant, Reiman said, but what do they mean? They could reflect reductions in the density or activity of key brain cells, which may or may not be connected to the risk of Alzheimer's as reflected by the APO E4 gene.

The metabolic changes appear to occur long before structural pathology in the form of plaques and tangles that are a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease (except for the neuritic plaques and neurofibrilary tangles believed to precede AD by as long as 50 years), he said.

"It is possible that the changes we observed represent very early age-related brain changes, but it is also possible that at least some of those changes represent an alteration in brain development," Reiman said.

He cautioned the audience not to jump to conclusions. Like genetic testing, PET is not sufficiently accurate to predict if or when a person will develop dementia, Reiman said. Moreover, the negative psychological and social impact of early warning on the individual could even outweigh the benefits of prevention therapy. At the same time, the study results could be used to develop preventive therapies that could be delivered at a very early age, Reiman said.

During the question-and-answer session, Reiman discussed his group's hypothesis that brain metabolism declines at different rates in different brain regions, depending on the subjects' preclinical or clinical stage of disease, or their age. The group hopes to track these declines in a future study.

One attendee asked whether the metabolic declines measured by PET correlated with the results of the neuropsychological tests. There was no correlation, Reiman said. But the researchers have noticed such correlations in an older group of subjects they are studying.

By Brian CaseyAuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 24, 2002

Related Reading

Imaging agent plus PET visualizes Alzheimer’s marker, July 23, 2002

PET scanning plus new molecular probe detects early Alzheimer's disease in vivo, January 10, 2002

PET findings predict future decline associated with neurodegenerative disease, November 8, 2001

Alzheimer's researchers tackle progression, prediction, October 2, 2001

Alzheimer's disease, Part I: PET yields surprising findings in hippocampus, September 7, 2001

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com