Using PET/CT scans to determine the presence or absence of coronary artery calcium in patients with chest pain can help determine which individuals have the greatest need for quick remedial action and an increased risk of a future major adverse cardiovascular event, according to a study presented March 16 at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2019 meeting in New Orleans.

Researchers from Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Salt Lake City found that patients with coronary artery calcium were more likely to undergo revascularization or coronary angiography with 90 days of scanning and have high-grade obstructive coronary artery disease. The information also could better direct patients with no evidence of calcification to more-appropriate noncardiac follow-up.

"We are interested in coronary artery calcium from a primary prevention and risk reduction standpoint," said principal investigator Viet Le, a physician's assistant and researcher at Intermountain. "It followed that with the imaging that we do at Intermountain, the question arose: Is there a better way in those folks who have not had coronary artery disease, but show with symptoms, to better stratify who should have a stress test and who should undergo a workup for something else?"

Where does it hurt?

Some 6 million people go to emergency departments in the U.S. annually with chest pain; approximately 3.8 million (63%) of them go on to have stress tests or undergo imaging. Naturally, many of these patients do not have a positive test result for myocardial infarction or other coronary event. While erring on the side of caution is always prudent, these cases do consume valuable hospital resources.

Viet Le from the Intermountain Heart Institute.

Viet Le from the Intermountain Heart Institute."That is a lot of money for the healthcare system and for the patient when perhaps there is a better way to improve which population we stress test," Le told AuntMinnie.com.

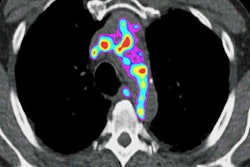

To delve into the cause of a patient's discomfort, PET/CT is a noninvasive option to determine the degree of coronary artery calcium. The deposits are associated with coronary artery disease, which could trigger a future major adverse cardiovascular event. It remains unclear, however, whether coronary artery calcium can predict the risk for such an event.

To try to determine the role coronary artery calcium might play in such prognostications, Le and colleagues retrospectively identified 5,547 patients with no history of coronary artery disease who came to Intermountain with chest pain between April 2013 and June 2016. The patients underwent rubidium-82 PET/CT scans for two purposes:

- To test for ischemia, which disrupts normal blood flow through the heart's arteries to its muscle tissue

- To determine the presence of coronary artery calcium deposits on the walls of the arteries, which would indicate atherosclerosis or plaque

The researchers visually assessed the absence or presence of coronary artery calcium and correlated those findings with patient outcomes relative to coronary angiography, high-grade coronary artery disease, and revascularization within the first 90 days after scans. In addition, they tracked major adverse cardiovascular events, such as death, hospitalization for myocardial infarction, and revascularization after 90 days but less than four years later.

Calcium count

In reviewing the PET/CT images, the researchers observed coronary artery calcium in 2,515 patients (45%), while 3,032 subjects (55%) showed no signs of calcium. In comparing their respective outcomes, they found that patients with coronary artery calcium fared much more poorly than those without.

| Outcomes based on presence of coronary artery calcium | ||

| Subjects with coronary artery calcium | Subjects with no coronary artery calcium | |

| Coronary angiography | 256 | 104 |

| High-grade coronary artery disease | 164 | 17 |

| Revascularization | 173 | 14 |

| Major adverse cardiovascular events | 173 | 72 |

From a clinical point of view, the results suggest that a "coronary artery calcium first" approach would better separate symptomatic patients who are prime candidates for additional evaluation, perhaps further functional stress tests, from patients who are at very low risk for coronary artery disease or a future major adverse event and should be referred for a noncardiac follow-up to diagnose the cause of their chest pain.

"When not stuck on coronary artery calcium, we could assess for maybe pulmonary, musculoskeletal, or gastrointestinal [causes], but we would be pretty darn sure it is not coronary-related," Le said. "On the other hand, if the patient has a calcium score greater than 0, these are folks that you can immediately send through to have a PET scan."

Given that ability to more efficiently redirect patients, patient throughput will be enhanced because emergency departments "would have eliminated, say, 50% of those folks who would've sat on your schedule," Le said. "It would improve those emergency department times in terms of patient turnaround and improve the efficiency of the system."

With these findings as their foundation, Intermountain clinicians have begun building a research protocol to "put our money where our mouth is, so to speak," Le added. "We are prospectively checking to see if a coronary artery calcification as a first strategy will indeed identify folks who do not need to have a PET/CT but are better served by being met earlier by a noncardiac physician. It is just a hypothesis at this point, but it is an observation with a real-world finding. Now we have to test it going forward, and we will."