PET imaging of brain activity in people with asthma shows that psychological stress is involved in triggering asthma attacks, according to a study published November 17 in Biological Psychology.

A team from the University of Wisconsin-Madison studied brain activity on PET scans in participants with asthma who took tests to mimic stress just minutes before imaging. The researchers found increased activity in specific areas known to trigger inflammation and airway obstruction in the lungs.

"Bidirectional communication between the brain and lung and may be key for addressing both psychological comorbidities in asthma and preventing future loss of disease control," wrote Melissa Rosenkranz, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the school's Center for Healthy Minds, and colleagues.

The activity identified on PET could be a target for new drugs or psychological interventions -- mindful meditation, for instance -- to help manage the disease, the authors added.

Asthma is one of the leading noncommunicable diseases worldwide, with more than 235 million people estimated to be living with the condition. Psychological stress has been shown to contribute to asthma symptoms by triggering an immune response, but the brain mechanisms responsible are not fully understood.

Moreover, research aimed at understanding the physiological underpinnings of asthma to develop new strategies to manage the disease has focused almost exclusively on the lungs and airways, according to the researchers.

In this study, Rosenkranz and colleagues aimed to elucidate the brain mechanisms involved.

The researchers recruited 30 people with allergic asthma from the Madison metropolitan area who had been diagnosed at least six months before the study. Patients had MRI exams at the outset of the study to establish baselines to measure subsequent brain activity.

Prior to the PET scan, participants were injected with FDG, a radiotracer visible on PET scans in areas of high glucose metabolism, a key activity in inflammation. The time required for the tracer to "uptake" in the brain is approximately 30 minutes.

During this period, participants were escorted to a nearby room where they performed a Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) designed to elicit a neurophysiological stress response in the brain. Patients were asked to prepare for and then give a continuous five-minute speech as if trying to convince a friend to read a book they liked, for instance. Then, they were asked to mentally count backward in increments of seven from the number 5,000.

Finally, participants were asked to verbally define several difficult words and perform a second mental arithmetic task involving multiplication.

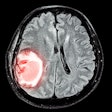

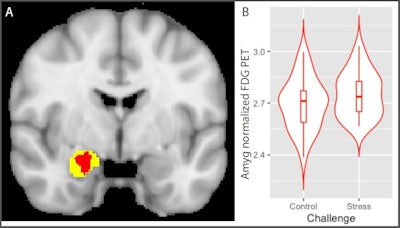

In the data analysis, researchers focused on the brain's amygdala area, which regulates the inflammatory immune response thought to be involved in triggering airway obstruction. The PET scans showed that activity in the amygdala was significantly increased during the TSST compared with a matched control task (p < 0.05 corrected).

Moreover, the researchers noted positive correlations between the increase in amygdala activity and a greater increase in stress hormones in patients' saliva, as well as circulating blood cytokines specific to lung inflammation.

"These findings suggest that heightened amygdala reactivity may contribute to asthma morbidity via descending proinflammatory sympathetic signaling pathways," the researchers wrote.

Psychological stress increases amygdala metabolism: Glucose metabolism in the insula is significantly greater during stress relative to control condition. A) Voxels showing a significant main effect of stress (stress > control; red) in a small-volume corrected analysis of a Harvard-Oxford amygdala defined region of interest (yellow; image thresholded at corrected p < 0.05). B) Distribution of mean values of normalized amygdala glucose metabolism in voxels (red) showing a significant main effect of challenge during stress and control conditions. Image courtesy of Biological Psychology.

Psychological stress increases amygdala metabolism: Glucose metabolism in the insula is significantly greater during stress relative to control condition. A) Voxels showing a significant main effect of stress (stress > control; red) in a small-volume corrected analysis of a Harvard-Oxford amygdala defined region of interest (yellow; image thresholded at corrected p < 0.05). B) Distribution of mean values of normalized amygdala glucose metabolism in voxels (red) showing a significant main effect of challenge during stress and control conditions. Image courtesy of Biological Psychology.The authors noted that a healthy, nonasthma comparison group was not part of the experimental design, which limits conclusions they can draw about the specificity of the findings. Nonetheless, the study demonstrates that the amygdala is a crucial nexus for bidirectional communication between the brain and lung in patients with asthma, they wrote.

Future studies may explore behavioral interventions, such as mindfulness training, which has been shown to strengthen the connectivity of brain networks that regulate the amygdala and reduce amygdala reactivity, as well as buffer the effects of stress on inflammation, Rosenkranz wrote.

"Further investigation of the model proposed here, including its modifiability with pharmacological and behavioral interventions, should be the focus of future research," the team concluded.