VIENNA - Promoting more effective collaboration among radiologists, nuclear medicine physicians, and radiation oncologists to improve imaging and radiotherapy outcomes is a core principle underpinning the lectures in today's special focus session on "Imaging and radiotherapy: all you need to know."

Among the speakers sharing their valuable experience and opinions will be Dr. Annika Loft, PhD, chief physician from the department of clinical physiology, nuclear medicine, and PET at Rigshospitalet at Copenhagen University Hospital in Denmark, and Dr. Regina Beets-Tan, PhD, an oncological and abdominal radiologist from Maastricht University Hospital and Oncology Center in the Netherlands, who will discuss the importance of collaboration with radiation oncologists.

The future of MRI will involve diffusion, perfusion, proliferation and hypoxia and automated image segmentation, according to Dr. Regina Beets-Tan, PhD.

The future of MRI will involve diffusion, perfusion, proliferation and hypoxia and automated image segmentation, according to Dr. Regina Beets-Tan, PhD.

Beets-Tan will take attendees on a journey through the future of oncologic imaging by addressing how new imaging biomarkers that highlight tumor heterogeneity can help radiation oncologists plan therapy. In an interview with ECR Today, she pointed out that radiologists have increasing value to radiation oncology, because of rapid advances in the approach to dose distribution in radiotherapy that require a combined professional approach.

"They need us to guide their treatment," she remarked. "You will hear from my co-lecturers in radiation oncology, Prof. Vincenzo Valentini and Prof. Karin Haustermans, about intensity-modulated radiation therapy and 'dose painting,' new ways to irradiate patients and to shape the dose distribution to the differences in radiobiology across tumors.Higher doses are given to certain tumor areas that are more radio-resistant, the so-called 'target within a target,' while sparing as much normal tissue as possible from damage."

Dose shaping gives rise to a need for ever more accurate imaging that identifies a tumor's heterogeneity and for imaging to evaluate response both during and after radiotherapy. Radiation oncologists want to know from radiologists which regions in the tumor are more resistant to their treatment and how these regions are responding during the radiation treatment so that the dose can be adapted, Beets-Tan stated.

Size alone is inefficient as a radiotherapy response evaluation tool, because it can mislead at times and is less accurate than functional and metabolic imaging, and she thinks PET and MRI have capabilities to offer improved imaging in this respect. MRI has the advantage of showing a high resolution of morphology, but also functional imaging of tumor biology and behavior, she pointed out.

Imaging biomarkers, in particular, can provide an objective measure of pathophysiological processes.

"This is why I think the future of MR imaging will involve diffusion, perfusion, proliferation and, further into the future still, hypoxia and automated image segmentation," Beets-Tan said. "This is where we radiologists will have a significant role in our collaboration with radiation oncologists."

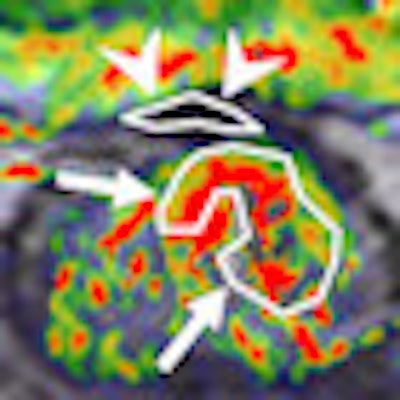

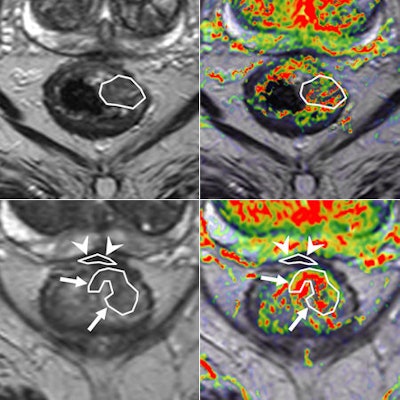

Perfusion MRI of a rectal tumor compared with histology. Top left: T2-weighted MR image of a patient with rectal tumor (encircled) before chemoradiotherapy. Top right: Corresponding perfusion MR image (K-trans map). There is a heterogeneity in tumor angiogenic activity with areas of higher (red) and lower K-trans values. Bottom left: T2-weighted MR image of the same patient after irradiation of the tumor. Bottom right: Corresponding perfusion MR image (K-trans map). Residual tumor (white arrows) is visualized, showing persistent heterogeneous angiogenic activity with areas of high (red) and low K-trans values (arrowheads pointing at fibrosis in the anterior rectal wall). All images courtesy of Dr. Regina Beets-Tan, PhD.

Perfusion MRI of a rectal tumor compared with histology. Top left: T2-weighted MR image of a patient with rectal tumor (encircled) before chemoradiotherapy. Top right: Corresponding perfusion MR image (K-trans map). There is a heterogeneity in tumor angiogenic activity with areas of higher (red) and lower K-trans values. Bottom left: T2-weighted MR image of the same patient after irradiation of the tumor. Bottom right: Corresponding perfusion MR image (K-trans map). Residual tumor (white arrows) is visualized, showing persistent heterogeneous angiogenic activity with areas of high (red) and low K-trans values (arrowheads pointing at fibrosis in the anterior rectal wall). All images courtesy of Dr. Regina Beets-Tan, PhD.However, she emphasized that before these biomarkers can be used in imaging practice, validation of the techniques is required to confirm whether "what you see is also what you get." Ultimately, in the multicenter setting, protocol standardization and implementation are needed to enable large patient cohort validation.

"After this, we would need to implement the techniques and incorporate them into clinical outcome trials," she said. "Treatment stratification in clinical trials based on imaging biomarkers will have to show whether the use of these will also lead to significant improvement in the quality and survival of patients. If we prove that, then imaging biomarkers will be ready for clinical practice."

Beets-Tan and her colleagues have validated functional MRI of the tumor and nodes in their own center, and are currently performing a multicenter study expanding participation to another 10 centers in the Netherlands. There has also been interest from other European countries and the U.S. to participate in the research.

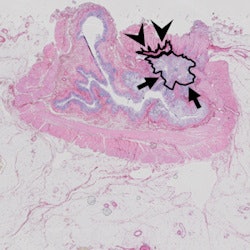

Same case as above. Histopathology confirmed the areas of residual tumor (arrows) and fibrosis (arrowheads).

Same case as above. Histopathology confirmed the areas of residual tumor (arrows) and fibrosis (arrowheads).

Adding further emphasis to the value of smooth collaboration between nuclear medicine physicians, radiation oncologists, and radiologists in her presentation, Loft plans to highlight that using PET/CT for radiotherapy planning requires a more multidisciplinary approach. Reflecting on her experience, she pointed out that in some hospitals, nuclear medicine physicians only performed the clinical diagnostic reading and exported the data to the oncologist who defined the tumor.

"These clinicians are not trained for this, so it can be quite difficult sometimes. It can lead to misinterpretation, and there's a risk of FDG-avid foci being included in the target volume, even though they are not malignant. I would like to keep the expertise with the expert," she said.

Ideally, a nuclear physician together with a radiologist should define what is malignant on the PET/CT scan. According to Loft, the oncologist is the expert in actually treating the patient and devising an individual treatment plan.

PET/CT provides the functional information of PET with the anatomical imaging of CT, and Loft points out that the combination helps with planning the volume for radiotherapy.

"You might find lymph nodes that are too small to be defined as malignant on CT but are definitely malignant on PET because of FDG uptake, so planning volume would increase. Conversely, planning volume would decrease if nodes are suspicious on CT but definitely look nonmalignant on PET," she noted.

In her talk, Loft will turn her attention to misreading of scans and reducing false positives. She will show clinical examples of how to increase and decrease the treatable tumor volume. A PET scan of lung cancer with potential lymph nodes involvement is a typical example of where misreading can occur.

"Somebody with little experience might think the lymph nodes need to be included in the total volume, but an experienced nuclear physician would determine whether they look positive or malignant, and if not then they should not be included," she explained. "An oncologist might include them to be sure nothing is missed, but then the patient has a large tumor volume for treatment, and this increases the radiation exposure and potential complications for the patient."

Conversely, compared to an oncologist, a nuclear medicine physician might also see bone metastases or affected lymph nodes that the oncologist might not notice. According to Loft, it is mainly a judgment of whether the FDG-avid foci are malignant or not. "Only experience can enable one to know the differences between malignant and nonmalignant foci for as long as we do not have a tracer for malignancy. There's no recipe for this," she said.

Addressing patient preparation is Loft's final issue. Most important, patients need to be precisely positioned in the same way for radiotherapy planning as for radiotherapy itself. "The patient needs to be in the exact same position for PET/CT scanning as for treatment, and this requires a lot of markings to define the exact location of the tumor. It's not enough to put up the PET/CT scanner and scan!"

Originally published in ECR Today on 8 March 2013.

Copyright © 2013 European Society of Radiology