Researchers from Stanford University are reporting promising early results in the development of a novel PET radiopharmaceutical designed to identify most bacterial infections. Their findings were published in the October issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

The PET tracer 6"-F-18-fluoromaltotriose is a derivative of maltose. If the researchers' efforts are successful, the imaging agent potentially could replace the tissue biopsy and/or blood and culture tests used to diagnose bacterial infection (JNM, October 2017, Vol. 58:10, pp. 1679-1684).

The challenge in battling infections is that bacteria mutate and become resistant to antibiotics. To address this issue, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has called for the development of novel diagnostics to detect and help manage the treatment of infectious diseases.

"What we need is something that bacteria eat that your cells, so-called mammalian cells, do not," said lead author Dr. Sam Gambhir, PhD, radiology department chair at Stanford University, in a statement from the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI). "Maltose ... is taken up only by bacteria because they have a transporter, called a maltodextrin transporter, on their cell wall that is able to take up maltose and small derivatives of maltose."

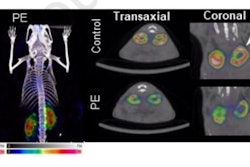

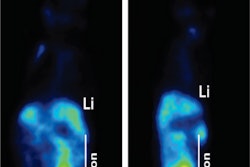

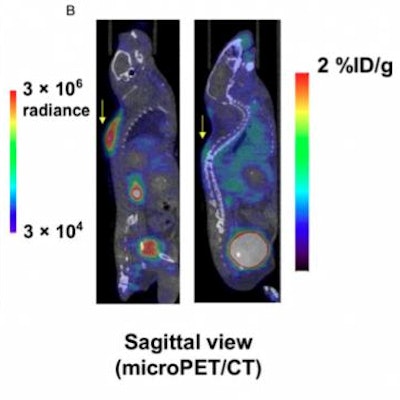

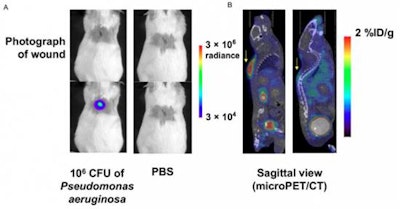

Stanford researchers tested the PET tracer 6"-F-18-fluoromaltotriose in a P. aeruginosa wound infection mouse model. Bioluminescence images (A) show the infected wound (left panel) and control mice (right panel). Sagittal slices (B) from a micro-PET/CT scan show the same mice one hour after intravenous administration of 6"-F-18-fluoromaltotriose. Images courtesy of JNM and Dr. Sam Gambhir, PhD, Stanford University.

Stanford researchers tested the PET tracer 6"-F-18-fluoromaltotriose in a P. aeruginosa wound infection mouse model. Bioluminescence images (A) show the infected wound (left panel) and control mice (right panel). Sagittal slices (B) from a micro-PET/CT scan show the same mice one hour after intravenous administration of 6"-F-18-fluoromaltotriose. Images courtesy of JNM and Dr. Sam Gambhir, PhD, Stanford University.In the JNM study, the researchers evaluated the tracer in several bacterial strains in cultures and in mouse models using a micro-PET/CT scanner.

The results show that 6"-F-18-fluoromaltotriose accumulated in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial strains. In addition, it was able to detect Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a clinically relevant mouse model of wound infection.

This particular maltotriose, labeled with F-18, is able to pick up bacteria that may be present anywhere throughout the body, according to Gambhir. The findings were further reinforced by the lack of a PET imaging signal from a site of infection that did not involve bacteria.

"The hope is that in the future when someone has a potential infection, this approach of injecting the patient with fluoromaltotriose and imaging them in a PET scanner will allow localization of the signal and, therefore, the bacteria," he said. "As one treats them, one can verify that the treatment is actually working -- so that if it's not working, one can quickly change to a different treatment."