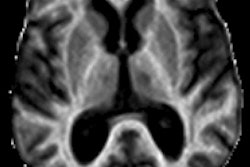

MR images show that when the thalamic and central regions of the brain atrophy, individuals have a greater chance of developing multiple sclerosis (MS) over the course of two years, according to a study published online April 23 in Radiology.

The findings suggest that MRI biomarkers, which reflect the development of such atrophy, may be helpful in future clinical trials to identify patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) who are at high risk for developing multiple sclerosis.

The study was led by Dr. Robert Zivadinov, PhD, from the department of neurology at the State University of New York and the Neuroimaging Analysis Center at the University at Buffalo.

According to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, clinically isolated syndrome is a neurologic episode caused by inflammation or demyelination (a process that erodes the myelin sheath that protects nerve fibers) in one or more sites in the central nervous system. People who experience CIS, which lasts at least 24 hours, may or may not develop multiple sclerosis.

The prospective study evaluated 216 CIS patients who ranged in age from 18 to 55 years and had two or more T2 hyperintense lesions on their MR images. Patients were treated with 30 µg of intramuscular interferon beta-1a once a week and were assessed with 1.5-tesla MRI at baseline, six months, one year, and two years.

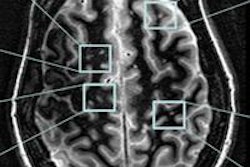

MRI measures of atrophy progression included cumulative number and volume of contrast-enhanced new and enlarged T2 lesions, as well as changes in whole-brain, tissue-specific global, and regional gray-matter volumes.

Zivadinov and colleagues found that over the course of two years, 92 (43%) of the 216 patients developed clinically definite multiple sclerosis. The mean time to first relapse was 3.1 months.

Of the 92 patients who developed multiple sclerosis, 38 (41%) were positive for contrast-enhanced new and larger lesions over the two-year follow-up, compared with 28 patients (23%) in the stable CIS group.

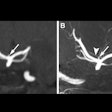

Lateral ventricle brain volume and the number of contrast-enhanced new and newly enlarged T2 lesions increased, while thalamic and whole-brain volume decreased. All of those factors were deemed significant differences between the MS and stable CIS groups over two years, and were indicators for the development of multiple sclerosis.

With a mean increase of 16% over two years in the 92 CIS patients who developed MS, the increase in the lateral ventricle volume was "by far the most rapidly deteriorating measure in our study," the authors noted.

The most likely explanation for this finding, they added, is the "development of subcortical deep gray-matter atrophy in the earliest phase of the disease, as shown in our study. Another explanation could be related to altered cerebrospinal fluid flow or velocity measures in CIS patients."

Using MRI to monitor the development of thalamic and central atrophy and tabulate contrast-enhanced lesions or assess their volume will help identify CIS patients at high risk for developing multiple sclerosis, Zivadinov and colleagues concluded.

In addition, the measurement of thalamic atrophy "is an ideal candidate for future CIS clinical trials," they wrote.