Researchers using MRI to study the Zika virus in a pregnant monkey said they were "shocked" at how quickly the virus spread from the animal to its fetus. The findings could shape efforts to develop a vaccine for the disease, according to a study published online September 12 in Nature Medicine.

The paper revealed how the Zika virus shut down certain aspects of brain development and caused a host of abnormalities after crossing from the placenta of a pregnant pigtail macaque to its unborn offspring. Ultimately, the hope is that this new information could lead to an effective prenatal treatment for human mothers-to-be who have contracted the virus.

"Our results remove any lingering doubt that the Zika virus is incredibly dangerous to the developing fetus and provides details as to how the brain injury develops," said lead author Dr. Kristina Adams Waldorf, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington, in a prepared statement. "This study brings us closer to determining if a Zika vaccine or therapy will prevent fetal brain injury, but also be safe to take in pregnancy."

Zika transmission

The Zika virus is transmitted by mosquitoes and can cause brain abnormalities such as cerebral atrophy, enlarged ventricles, and a small cerebellum, as well as eye and vision deficiencies. Unlike other viral infections, the symptoms of infection with the Zika virus often are quite mild and vary greatly. While some people have no symptoms, others develop fever, muscle aches, rash, and sore and swollen eyes.

Dr. Kristina Adams Waldorf of the University of Washington.

Dr. Kristina Adams Waldorf of the University of Washington.The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates there are 157 women in the U.S. with the Zika virus. The total has tripled since the CDC on September 9 changed the way it counts Zika carriers. The agency now includes women who test positive for the virus, along with pregnant women with both positive blood results and Zika symptoms.

To learn more about how the Zika virus is transmitted from pregnant women to their fetuses, the University of Washington researchers chose to study the pigtail macaque, because such primates "most closely mimic human gestation in many key respects," the authors wrote. The structure of the placenta, the timing of nerve and brain development, and gray and white matter in the brain closely resemble those of humans (Nature Medicine, September 12, 2016).

In the experiment, the Zika virus was administered to a pigtail macaque 119 days into its gestation, which is equivalent to approximately 28 weeks of a human pregnancy. The amount of virus injected was similar to the amount a person might contract from the bite of a virus-carrying mosquito.

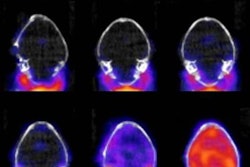

The first MRI scan of the fetal brain was performed 10 days after inoculation and showed hyperintense foci in the occipital-parietal regions surrounding the lateral ventricles. Eventually, the hyperintense foci enlarged on the right side but reversed and became hypointense on the left, which was linked with a loss of brain volume and ventricular collapse.

"We were shocked when we saw the first MRI of the fetal brain 10 days after viral inoculation. We had not predicted that such a large area of the fetal brain would be damaged so quickly," added co-author Dr. Lakshmi Rajagopal, an associate professor of pediatrics, in the statement.

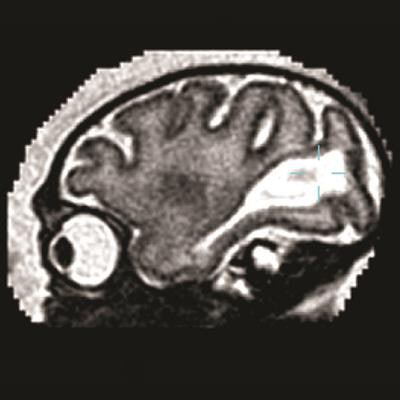

Sagittal MRI of the fetal brain of a pigtail macaque infected with the Zika virus. The large white region is abnormal and indicates an accumulation of fluid in the brain. Image courtesy of the University of Washington.

Sagittal MRI of the fetal brain of a pigtail macaque infected with the Zika virus. The large white region is abnormal and indicates an accumulation of fluid in the brain. Image courtesy of the University of Washington.The researchers also tracked another fetal brain anomaly. Large posterior ventricular cerebrospinal fluid spaces remained late into the unborn primate's gestation, along with increased water content in surrounding posterior white matter. Under normal conditions, those regions become smaller as the parietal and occipital lobes develop late in the pregnancy.

The results suggest that a therapy to prevent fetal brain injury must be a vaccine or a prophylactic medicine taken at the time of the mosquito bite, Rajagopal said.

"By the time a pregnant woman develops symptoms, the fetal brain may already be affected and damaged," she said.

The MR images revealed no abnormalities in the cortical area, brainstem, or cerebellum. There also were no indications of injury in other maternal or fetal organs. The Zika viral genome, however, was present in other fetal tissues, including the eye, liver, and kidney.

Effective treatment

Given the changes in brain development, the researchers concluded that the Zika virus had crossed through the placenta and into the unborn primate's brain. In addition, they noted a higher virus level in the fetus' brain than in the mother.

"Our findings of arrested fetal brain growth and viral neuroinvasion are consistent with the congenital Zika virus syndrome seen in humans," the authors wrote. "We demonstrate that a clinically inapparent maternal Zika virus infection during pregnancy has the capacity to result in fetal brain injury in a pregnant pigtail macaque."

Adams Waldorf and colleagues recommended additional studies to explore how fetal defects develop, adding that the primate model "may have significant utility for testing novel vaccines and therapeutics to prevent the congenital Zika virus syndrome."