Dr. Joshua Fenton of the University of California, Davis has emerged as one of the most prominent skeptics of computer-aided detection (CAD) technology for breast screening. Fenton is again questioning CAD's effectiveness in a new study published online April 15 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Fenton first raised a ruckus in 2007 with a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine finding that CAD was associated with reduced accuracy for breast screening, but no difference in the detection rate of invasive breast cancer. He followed that study with research in 2011 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute that found that CAD increased recall rates.

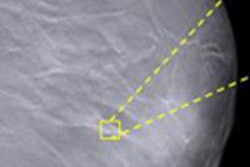

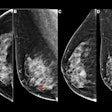

This week's study assessed the short-term outcomes of screening mammography using CAD by measuring the difference in detection rates for invasive cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) between sites using CAD and those that didn't. The theory is that if CAD is detecting more cases of DCIS, it could be a sign that the technology is contributing to "overdiagnosis" by finding cancers that may not prove to be a threat during a woman's lifetime.

Rising use follows reimbursement

Medicare began reimbursing for CAD used with mammography in 2001; from 2001 to 2006, CAD prevalence increased from 3.6% to 60.5%, wrote Fenton and colleagues. Some studies show that CAD increases the rate of breast cancer detection -- as well as the rate of false positives. But is CAD finding the right cancers? And does it really help older women?

Because randomized clinical trials suggest that screening mammography's positive effect on breast cancer mortality comes from detecting invasive cancer, it's important to assess CAD's effect on detecting invasive and noninvasive breast cancer.

"We conducted this research because of the uncertainties that exist about the clinical impact of CAD, particularly its impact on breast cancer diagnosis," Fenton told AuntMinnie.com. "Even though there have been very few multicenter studies on the technology, it's being used in the U.S. with more than three-fourths of screening mammograms."

Using U.S. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Medicare data, Fenton's team reviewed health records for 163,099 women ages 67 to 89 years receiving 409,459 mammograms. The group investigated associations between CAD use during screening mammography and the incidence of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive breast cancer, invasive cancer stage, and diagnostic testing.

The team found that use of the technology was associated with greater DCIS incidence but no difference in invasive breast cancer incidence. A woman receiving mammography screening at a site using CAD had a higher adjusted odds ratio, 1.17, for receiving a diagnosis of DCIS compared with those screened at sites without CAD (p < 0.001).

Meanwhile, Fenton and colleagues reported that there was "no difference" in detection rates for invasive cancer between sites using CAD and those that didn't. Women in the CAD group had a slightly higher adjusted odds ratio, 1.06, for having stage I cancer (p < 0.001), but a slightly lower adjusted odds ratio, 0.92, for more advanced cancer from stages II to IV (p < 0.001).

CAD was also associated with increased odds of having further tests or procedures, such as diagnostic mammography, breast ultrasonography, and breast biopsy. Women in the CAD group had an increased odds ratio of 1.28 for receiving diagnostic mammography, 1.07 for receiving breast ultrasound, and 1.10 for receiving breast biopsy (p < 0.001 for all three categories).

Why the rapid uptake of CAD into clinical practice? In part because of Medicare reimbursement, but also due to an understandable caution on the part of breast imagers, Fenton said.

"There's legitimate concern among radiologists about the risk of missing breast cancers, and CAD was designed to increase the cancer detection rate," he said. "It boosts sensitivity, but not necessarily the specificity."

Treatment of DCIS detected by CAD may prevent progression to lethal invasive breast cancer and may avert more extensive treatment of subsequent invasive cancer, the team wrote -- but on the other hand, recent estimates suggest that one in four screen-detected invasive breast cancer cases are detected and treated in women who would have died of other causes without screening.

"Our study findings give us additional information about overdiagnosis, which is of particular concern in an older Medicare population," Fenton said. "If a woman in her 40s is diagnosed with DCIS, there's higher confidence that treating it will prevent an eventual invasive cancer. But in an 80-year-old woman, it's questionable whether treating DCIS will benefit her."