Early post-treatment PET/CT scans in patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer may predict whether they later develop hypothyroidism, according to a study published on October 10 in Cancer Imaging.

Taiwanese researchers analyzed F-18 FDG radiotracer uptake in the thyroid glands of patients who received follow-up PET/CT scans after radiotherapy treatment. They found that increased uptake indicated impending hypothyroidism in a significant number of patients.

"In patients with these high-risk findings, vigilant surveillance of thyroid function is warranted," wrote corresponding author Dr. Mu-Hung Tsai, a radiation oncologist at National Cheng Kung University in Tainan, Taiwan.

Head and neck cancer is the sixth most common cancer in the world. Up to 50% of patients treated with radiation therapy develop hypothyroidism as a result, with the disorder occurring in many cases up to three years after treatment. Hypothyroidism is usually diagnosed with blood tests that measure thyroid function. The condition is treated with hormone replacement therapy.

In locally advanced head and neck cancers, F-18 FDG-PET/CT is the preferred method for evaluating patient responses after radiotherapy. These patients are likely to receive PET/CT as part of their standard care, the authors wrote.

The researchers explored whether adding studies of thyroid activity on these early post-treatment PET/CT scans may help predict hypothyroidism.

The group screened 460 patients who underwent radiotherapy for head and neck cancer at National Cheng Kung University Hospital between 2005 and 2017. Of these patients, 185 underwent PET/CT after completion of definitive radiotherapy; restricting the timing of the PET/CT scans to within 180 days of completing treatment yielded 52 patients.

The median time to PET/CT from completion of radiotherapy was 93 days, and the median thyroid function follow-up period was 3.3 years. According to the findings, 22 patients (42%) developed hypothyroidism and 30 (58%) did not. The median time to hypothyroidism was 22.7 months after treatment and 17.6 months after PET/CT.

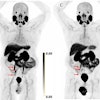

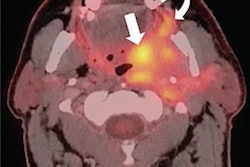

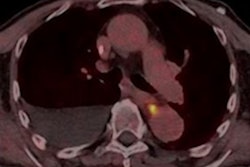

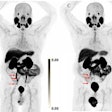

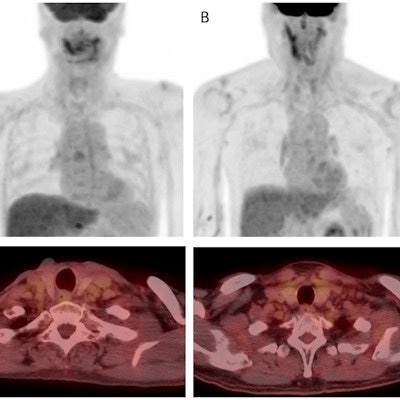

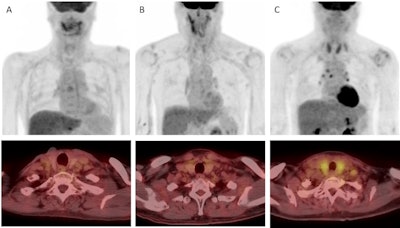

First, the researchers visually assessed thyroid uptake on PET/CT. Two patients (4%) had diffuse thyroid uptake (visual grade 3), 32 (62%) had visual grade 2 uptake, and 18 (35%) had visual grade 1 uptake. The two patients with visual grade 3 uptake later developed hypothyroidism.

Examples of thyroid visual grade in the study cohort (upper: maximum intensity projection, lower: transaxial view). A) In grade 1, thyroid uptake is less than blood pool uptake. B) In grade 2, thyroid uptake is equal to or higher than blood pool uptake, but less than liver uptake. C) In grade 3, thyroid uptake is equal to or higher than liver uptake. Image courtesy of Cancer Imaging.

Examples of thyroid visual grade in the study cohort (upper: maximum intensity projection, lower: transaxial view). A) In grade 1, thyroid uptake is less than blood pool uptake. B) In grade 2, thyroid uptake is equal to or higher than blood pool uptake, but less than liver uptake. C) In grade 3, thyroid uptake is equal to or higher than liver uptake. Image courtesy of Cancer Imaging.Next, a quantitative analysis of thyroid functioning volume revealed that F-18 FDG radiotracer uptake was significantly lower in patients who developed hypothyroidism than in those who did not (10.61 cm3 versus 16.30 cm3, p < 0.001).

Lastly, a clinical algorithm that combined visual grading of thyroid uptake combined with a thyroid functioning volume capped at 14.01 cm3 predicted late-onset hypothyroidism with an area under the curve value of 0.89, according to the findings.

"Visual grading of thyroid uptake combined with thyroid functioning volume derived from early post-treatment PET/CT significantly correlated with the development of [hypothyroidism] in patients with head and neck cancer," the authors wrote.

While F-18 FDG-PET/CT has been used to predict hypothyroidism in head and neck cancer patients treated with immunotherapy, this is the first report using PET/CT to predict radiation-induced hypothyroidism, according to the authors. As such, the study was limited by the small group of patients, and generalization of the results should be exercised with caution, they wrote.

However, the researchers noted that the date of the early post-treatment PET/CT scans preceded the appearance of abnormal thyroid function in the study group by a median of 1.5 years. This finding suggests that incorporating thyroid parameters on early post-treatment PET/CT may enable the early diagnosis of hypothyroidism in patients who have undergone radiotherapy.

"Careful symptom monitoring and close surveillance of thyroid function are warranted in patients with diffuse thyroid F-18 FDG uptake, even in those with seemingly normal thyroid function," Tsai and colleagues concluded.