Anthrax:

Clinical:

Bacillus anthracis is a rod shaped, spore forming organism that primarily infects herbivores [1]. Humans can acquire the infection by agricultural or industrial exposure to infected animals or animal products (i.e.: shepherds, farmers, and workers in plants using animal products) [1]. Human to human transmission has not been reported [1]. Anthrax most commonly produces a cutaneous infection (95% of cases), but inhalation of spores can result in pulmonary disease. The organism can also produce gastrointestinal disease [1]. Inhalational anthrax has a biphasic presentation following an incubation period of about 6 days [1]. The infection begins with the incidious onset of non-specific influenza-like symptoms, but within days progresses to an overwhelming pulmonary infection with severe dyspnea, septic shock, and death [1].

It is estimated that between 8,000-10,000 inhaled spores would be the lethal amount for 50% of human subjects [1]. Spores greater than 5 um in size are deposited in the upper airways and effectively cleared by the mucociliary system [1]. Spores between 2-5 um in size are able to reach the alveolar ducts and alveoli. Here the spores are engulfed by alveolar macropahges and transported to mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes [1]. After a period of germination, a large amount of antrax endotoxin is produced [1,2]. The regional nodes are quickly overwhelmed and the toxin enters into the circulation with resultant edema, hemorrhagic adenitis, and septic shock [1].

Unfortunately, Anthrax can also be used for biological terrorism. According to the World Health Organization, 50 kilograms of aerosolized anthrax spores dispersed by airplane two kilometers upwind from a population center of 500,000 unprotected people could kill about 95,000 individuals [1]. Anthrax spores can survive for many years in arid and semiarid environments [1]. The spores are highly resistant to drying, boiling for 10 minutes, and most disinfectants [1]. A temperature of 120 degrees C for at least 15 minutes is normally used to inactivate spores [1].

Antibiotics and supportive care in an intensive care setting are the mainstay of therapy for inhalational anthrax [1].

X-ray:

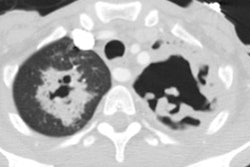

On CXR the initial manifestations are non-specific. Later there is widening of the mediastinum due to massive lymphadenopathy. These nodes appear of increased density on non-contrast CT imaging due to hemorrhagic lymphadenitis [1]. Pleural effusion is common [1,3]. Focal parenchymal consolidations can be found in about 25% of cases (due to focal hemorrhagic, necrotizing pneumonia [1].

REFERENCES:

(1) Chest 1999; Shafazand S, et al. Inhalational anthrax: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. 116 :1369-76

(2) Radiology 2002; Earls JP, et al. Inhalational anthrax after bioterrorism exposure: spectrum of imaging findings in two surviving patients. 222: 305-312

(3) AJR 2002; Krol CM, et al. Dynamic CT features of inhalational anthrax infection. 178: 1063-1066